Many miss the true meaning of the memorial communicated by a symbol. The symbol is not some hidden detail, but instead is deceptively obvious, repeated again and again in plain sight.

What is the Symbol?

NPS

Recognized around the world as a symbol of the United States and one of its great presidents, the awe-inspiring Lincoln Memorial attracts millions of visitors every year. In the main chamber of the memorial, some of these visitors lean against the back wall, crane their necks and contort their faces looking for a face in the rear of Lincoln's head. Some will attempt to decode Lincoln's hands. Looking for some deeper meaning, convinced that it must be here in this exalted chamber, most of these visitors will end up shaking their heads, shrugging, and walking away unconvinced of what they have seen. The irony is that the deeper meaning surrounds them, and has probably gone overlooked.

While distracted by myths about faces in hair and letter-signing hands, many visitors miss the true meaning of the memorial and the ubiquitous symbol that carries that meaning. Instead of being hidden somewhere inaccessible, the symbol is deceptively obvious, right there under Abraham Lincoln's hands. This symbol is so overlooked that, even when pointed out, many observers will not recognize it. The symbol is that of fasces (FAS-eez), a bundle of rods bound by a leather thong. Repeated throughout the memorial, the fasces reveal the higher meaning of the Lincoln Memorial and the way the memorial's designers meant to honor Abraham Lincoln.

What do fasces represent?

In ancient times, fasces were a Roman symbol of power and authority, a bundle of wooden rods and an axe bound together by leather thongs. Fasces represented that a man held imperium, or executive authority. Exercising imperium, a Roman leader could expect his orders to be obeyed, could dole out punishment, and could even execute those who disobeyed. The fasces he carried symbolized this power in two ways: the rods suggest punishment by beating, the axe suggests beheading. On its surface, the fasces imply power, strength, authority, and justice.

Fasces on the Lincoln Memorial Exterior

NPS

As one approaches the Lincoln Memorial from the plaza below, he or she passes by the first of these fasces at the base of the main stairs. The carving is easily missed even though it is more than ten feet tall, but to miss it is to miss the introduction to the theme of the memorial. On the end of the wall is a carving of rods with an axe bound by a leather thong, the classic Roman fasces. The fasces indicate the power and authority of the state over the citizens, commanding respect. But there is a twist. A bald eagle's head sits atop the axe, an American touch on an ancient Roman symbol. Adding to the American-ness, there are thirteen rods shown in the fasces, suggesting the thirteen original states that achieved independence from Britain and formed the United States. Seen as symbols of the states — and the American motto "E Pluribus Unum," or "Out of Many, One," — the rods bound together suggest the union of the states and their bond by the Constitution. Each state is weaker individually, but together, they are stronger. This concept is so important that it is presented long before visitors reach the building itself and see the representation of the Savior of the Union.

The Fasces as a Symbol of Union

NPS / John Donoghue

The structure itself echoes and amplifies the idea of a strong union. By architect Henry Bacon's design, the perimeter of the Lincoln Memorial boasts 36 Doric columns representing the 36 states in the union Lincoln fought to preserve. The names and admission year of these states are engraved above the marble columns, the years not coincidentally shown in Roman numerals. The Lincoln Memorial is physically held up by the columns, standing strong because all the columns are working together. Without each column, the building would fall, just as the nation would fall without all its states. This concept of the memorial was incorporated into an object you may have in your pocket right now. Pennies minted between 1959 and 2008 depict the Lincoln Memorial on the reverse with the words "E Pluribus Unum" above the memorial. The implication is that the entire structure is a representation of the fasces, a representation of strength through unity, a monument not only to Lincoln but to the Union itself.

Fasces in the Murals

NPS

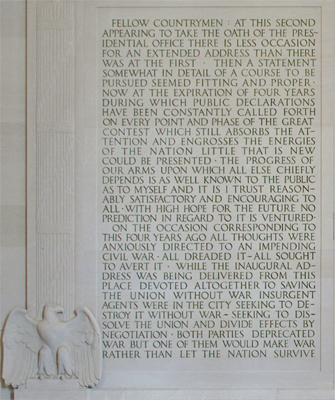

Fasces in the Quotes

NPS

On the opposite wall, Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address reviews the devastating conflict and Lincoln's desire to see an end to slavery, yet it famously closes with the idea of reunifying the nation "with malice toward none, with charity for all." Jules Guerin's mural depicts themes of reunion, charity, and fertility. Tucked in the margins of the address, axe-less fasces rise alongside the words, reinforcing Lincoln's theme of reunion, for the nation is stronger when all the states are bound together.

Fasces in Abraham Lincoln's Statue and Beyond

NPS

The centerpiece of the memorial is Daniel Chester French's sculpture of Abraham Lincoln. Our eyes gravitate toward his, contemplating his mood and expression. We sense the tension and strain he is under, but also the command and presence he has. Because we are naturally drawn to the human component of the statue, we can easily overlook the flag draped behind him and the fasces beneath his hands symbolizing the Union he strained to preserve. To drive the point home, the inscription above the statue reads: "In this temple as in the hearts of the people for whom he saved the Union, the memory of Abraham Lincoln is enshrined forever."

In the context of the time in which the memorial was built, Lincoln's status as the leader who "saved the Union" was paramount. The Lincoln Memorial's symbolic use of fasces, the unifying feature of the memorial, emphasizes the importance of the union of the states and Lincoln's role in preserving that union. It is not a symbol we commonly see today, or at least we do not commonly notice it, but the symbol is to be found throughout the capital city. Fasces appear in the Oval Office, the House of Representatives, at the base of the Lady Freedom statue on the Capitol, on the U.S. Senate Seal, and in the copy of Jean-Antoine Houdon's sculpture of George Washington inside the Washington Monument. Fasces also appeared on the Mercury dime from 1916 to 1945, subtly transformed into the torch we see on today's dime in 1946, shortly after the close of World War II.

A Legacy of Fasces

NPS

Last updated: December 9, 2019