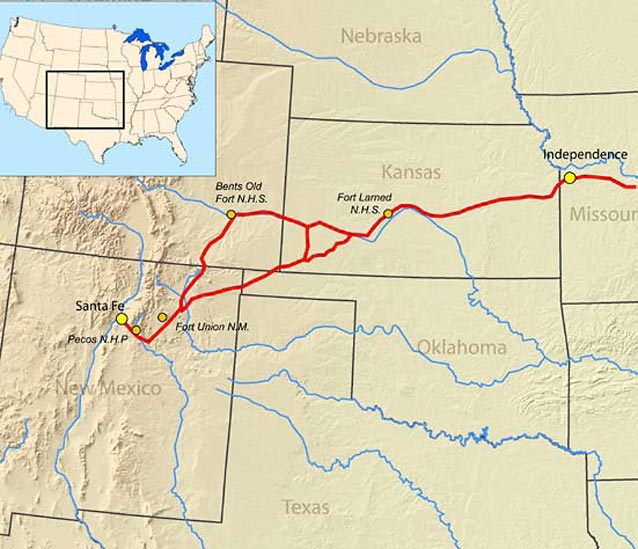

Covering approximately 800 miles, the Santa Fe Trail extends from Independence, Missouri to present day Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Trail originally began in Franklin, Missouri, but the trail head was moved to Fort Osage and, by 1827, to Independence.

Prior to the U.S. acquiring New Mexico in 1848, the area (New Mexico) was part of Mexico. In the early 1800s, Spain ruled Mexico and controlled its New Mexico colony, prohibiting manufacturing and international trade. U.S. visitors to Santa Fe recognized opportunity in the area for manufactured goods and supplies. In 1821, the Mexican people revolted and won independence from Spain, and gone were the impediments to trade.

The Santa Fe Trail was first used in 1821 by William Becknell. Becknell packed goods from Franklin, Missouri, to Santa Fe with five companions. The party left on September 1, 1821 and reached Santa Fe on November 16th (Duffus 1972). Becknell profitted from the venture and made additional trips. On his third trip, he found a route that could be used by wagons (Santa Fe Trail Association (SFTA) 2009)-- the first to be driven over the plains to New Mexico (Gardner 1993). Becknell was credited as the “Father of the Santa Fe Trail.” Encouraged by Mexico, other business people followed, and trade developed with Santa Fe.

Courtesy Denver Public Library, Western Colorado.

Pack mules were originally used for trade travel, but mules and oxen worked well in pulling the light, sturdy wagons that were soon used. The wagons were designed for travel over rough, level terrain. Covering about 15-18 miles per day, the 800-mile journey took about two months (USDOI 1976).

In the following years, the Santa Fe Trail served as a vital commercial and military highway. First having served as an international trade route between the U.S. and Mexico, it provided the U.S. a route to invade New Mexico in 1846 during the Mexican-American War. After the U.S. acquired the Southwest, the Trail facilitated U.S. economic development and settlement of the region (SFTA 2009).

NPS

Extending from Independence, Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico, the Trail passed through Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and New Mexico. A portion of the trail branches into the northern, Mountain Route, and the southern, Cimarron Route. The Cimarron Route, or Cutoff, was the original path of the Trail (the length of the Trail via this route was 800 miles). The Cimarron Cutoff was 100 miles shorter than the Mountain Branch, but travelers along its path had to contend with 40 miles or so of desert before reaching the Cimarron River (USDOI 1976). Infrequent waterholes and encounters with the Kiowas or Comanches threatened travelers along this stretch. The Mountain Branch also passed Bent’s Fort in Colorado, which became a popular trading post. The two routes diverge in Southwestern Kansas at Cimarron, and meet back up near Fort Union, New Mexico. The Mountain Route was used after 1845. During the period of the Civil War, the Cimarron Route was used very little due to conflicts with Native Americans (USDOI 1976).

Tomye Folts-Zettner / NPS

The Santa Fe Trail Association website provides a detailed description of the trail route, including references to rivers and present-day towns and roadways. USDOI (1976) also provides a detailed description of the Trail route.

The Santa Fe Trail passes through the Central Lowlands, the Great Plains, and the southern Rocky Mountains Physiographic Provinces (USDOI 1976). The Central Lowlands receive about 35 inches of rain per year. This area in eastern Kansas is characterized by rolling plains situated in between northeast-southwest oriented escarpments. Leaving the Central Lowlands, the Trail enters the Great Plains Physiographic Province in central Kansas. From this point, and into Oklahoma and Colorado, the topography is mostly flat with some rolling hills and sand dunes. Grama-buffalo and sandsage-bluestem grasses dominate the native vegetation. Woodlands occur along the rivers and streams, with trees such as elm, ash, and cottonwood. Occurring primarily in the spring and summer, annual precipitation is less here—on average 15 inches. Tableland-type topography characterizes the Trail route in southern Colorado and eastern New Mexico. Vegetation is basically the same as in the Great Plains, except for the juniper-pinon woodlands that occur at higher elevations. Continuing on into New Mexico, the Trail route changes considerably; plains vegetation is replaced by juniper-pinon and occasional pine-Douglas fir forests. Annual precipitation is about the same as in the Great Plains.

Part of a series of articles titled The Santa Fe Trail.

Last updated: March 18, 2016