Part of a series of articles titled Savannah and Chatham County, Georgia, WWII Heritage City Lessons.

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Shipbuilding in Savannah and Chatham County, Georgia, World War II Heritage City

“22 Military Posts in Georgia Are Designated in Closed Area,” The Atlanta Constitution, September 10, 1942, p. 2.

About this Lesson

This lesson is part of a series teaching about the World War II home front, with Savannah and Chatham County, Georgia designated as an American World War II Heritage City. The lesson contains readings and photos to contribute to learners’ understandings about shipbuilding in Savannah, such as the production of Liberty ships and minesweepers. Civilian workers, including women and youth, contributed to the efforts.

Objectives:

- Describe the purpose and contributions of the shipbuilding industries in Savannah and Chatham County.

- Explain how labor demands were met, including the training and employment of women and youth.

- Compare local, historical perspectives on service to synthesize and connect to larger wartime perspectives and themes.

Materials for Students:

- Photos (can be displayed digitally)

- Readings 1, 2, 3 (and optional extension)

- Recommended: Map of Savannah, Georgia (one map sketch included as photo in this lesson)

Getting Started: Essential Question

How did shipbuilding in Savannah and Chatham County lead to the success of the Allies during World War II?

Read to Connect

Note: This article is when Savannah Shipyards, Inc., led operations. The US Maritime Commission took over the Savannah Shipyards, Inc., in January 3, 1942. It then began operating under the Southeastern Shipyards Corporation. This occurred after condemnation proceedings (safety and operational failures) and failing to comply with contracts. The lesson extension includes an article connected to this background.

Teacher Tip: Pre-teach the term “Hog Islanders.” This was slang for ships built in WWI at the Hog Island emergency shipyard in Philadelphia. The ships were used for cargo and troop transport.

Work Begins on $20,000,000 Ship-Building Plant at Savannah

Huge Track Cleared on Which Navy Units Will Be Built

By Harold Martin, The Atlanta Constitution, Sunday, October 26, 1941, p. 20.

. . .W.R. Crowley, president of the Savannah Shipyards, Inc., said here yesterday that the huge new plant east of town—on the site of an old World War shipyard—would lay its first keel on the first of December. The first boat will come off the ways about six months later, and after that, they will be shelling out of there like peas, one every four months probably.

They will be grand ships, too, a long step ahead of the old ‘Hog Islanders’ of World War days. In fact, Mr. Crowley grows quite lyrical when he speaks of them.

They will be all steel, 424 feet long, with a 58-foot beam, and by welding instead of riveting and doing the whole job on the ways, they can be put together in half the time it took to build their Hog Island forefathers.

Well Armed

They will be well armed, with a gun foundation aft which will take a five-inch gun and there will be four heavy machineguns for fighting off dive bombers. They aren’t fighting ships, of course, but cargo carriers which will carry a load of 10,000 tons.

They are, according to Mr. Crowley, sleek, good-looking and comfortable ships, with only four men to a room in the crew quarters instead of eight on the old vessels, and the berths are longer and wider, with softer mattresses. Crew quarters will be in one house amidships, except for the gun crew. They will be located on the poop deck, wherever that is, so they won’t have to chase the length of the deck in heavy weather.

. . .These ships aren’t being built, Mr. Crowley says, to rot in the yards somewhere when the war is over. They will last forever, and when the emergency is done, the Maritime Commission sees them as the nucleus of a great American Merchant Marine.

Permanent Plant

Nor does Mr. Crowley expect to see his shipyard melt into the sand and mud along the banks of the Savannah when the war is over. The plant is being built so that it can turn out huge oil tankers after the war. He believes the country will need plenty of tankers then. And the Maritime Commission assures him they will have plenty of work for him for many years to come.

. . . So the whole plant, when through, will be about a 10-million-dollar investment, building at least 25 liberty ships at a cost of approximately $44,000,000. It will employ about 2,500 people at first, and later around 4,000.

Savannah Shipyards, Inc., of course, is not the only firm building ships down here in the greatest boom of its kind in Savannah’s history. Up the river, north of town, the Savannah Machine and Foundry Company, a boat repairing firm, has put up a million-dollar plant. . . . Young Mingledorff, a graduate of Georgia Tech in 1936, estimates that his plant, when running full blast, will put about 1,900 people to work, and the total cost of the nine sweepers will be around 15 or 16 million dollars.

The Mingledorff establishment is also designed as a permanent place, specializing in building smaller craft for the Navy after the war is over. . . .

2 Georgia Labor Filters Supply Dixie Shipyards

Centers at Savannah and Brunswick Opened to Meet Increasing Demands

By Eulalie McDowell, The Atlanta Journal, Sun, Sep 20, 1942, p. 14.

Two labor induction centers – war production man power procurement agencies that parallel the Army’s method of funneling men into the armed forces—were established this week in Georgia.

Located at Savannah and Brunswick, the induction centers will meet the increasing demand for trained labor for shipyards in the two cities by making readily available youthful welders, sheet metal workers, riveters—both boys and girls—who can speed ships into service.

The only other labor induction center in the Southeast is at Mobile, Ala., where there also is great demand for shipyard workers.

Draw from Six States

Designed to function as selective service induction points, these two Georgia centers have six states in the Southeast from which to draw workers to answer the urgent calls sent out by shipyards.

Now supplying only the needs of shipbuilders in Georgia, the same sort of service will be extended in months to come when the aircraft industry begins to make its demands on labor with the operation of the Bell bomber plant in Cobb County.

These centers were established and are being operated by the National Youth Administration in co-operation with the War Man Power Commission, United States Employment Service and the shipyards.

This week Savannah shipyards sent out a call for more than 100 welders. Almost simultaneously the demand was met by the NYA, which supplied boys from Florida, Tennessee, South Carolina and Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. How can labor be supplied so quickly? The answer is simple under the induction center plan. . . .

Hard Man to Fool

Howard G. Blakesley, operations officer at the Savannah project, is a hard man to fool and no youth gets his okay who can’t get on an assembly line and produce. When he says a boy is ready for the shipyards that boy is ready.

With all tests behind, NYA authorities assist the youth in filling out the job application forms, which are only a formality, since the youth is assured work—and then see him safely through the ropes at the United States Employment Service and thence to the shipyards.

The entire procedure from the time the youth arrives at the center until he goes to work in the shipyard rarely requires more than a week. In many cases the time has been reduced to three days.

‘They just about cleaned us out this week,’ Chester A. May Jr., youth personnel officer at the Savannah NYA center, asserted as he returned from delivering 20 boys to the shipyards.

Next week Mr. May expects to answer calls for workers by supplying possibly 100 girls to the yards.

May Depend on Girls

Girls, in this war, are producing like the men and, should the draft age be lowered, will be the major sources of labor.

The average age of youths who enter these induction centers is ‘about 17,’ according to Gilbert C. McLemore, project manager.

‘The shipyards now say 17 is the golden age,’ Mr. McLemore said. ‘With the draft age now 20, the shipbuilders can look forward to three fruitful years of production before the boys are sent to an Army induction center.’ . . .

Ocean Broom Factory

The Atlanta Journal, September 10, 1944, p.5.

Georgia has one of the few “ocean broom” factories in the country.

Down at the Savannah Machine and Foundry shipyard, the minesweepers that clear the way for invasions and multiple-front openings-up are being put together as fast as the steel can be welded. This shipyard is just now starting on its 21st minesweeper since November 1941. Minesweepers from Savannah have seen service in all three of the invasions making the waters safe for Allied ships and troops in the African, Italian and Normandy landings.

It takes four months to build a minesweeper, and only one minute to blow it to bits. The spearhead of a minesweeper squadron is one of the most dangerous spots of any war. The waters surrounding any probably beachhead are always thoroughly mined—full of the hidden death-traps. Minesweepers may be called upon to stand off shore and protect the landing troops. One of the Savannah-built minesweepers was so close to shore in the invasion of Italy that Germans on the beach were shooting at her. . .

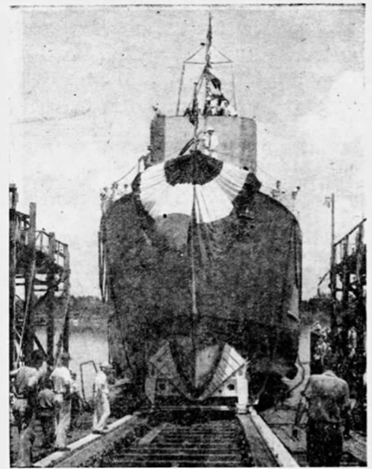

An unaccustomed visitor to the shipyard is likely to be made aware, for the first time, of what a tremendous job it is to build and equip our fighting ships. The great steel shells on the ways are swarming with workers, small and busy against the background of shapely metal – climbing, hammering, welding, painting. There are 3,000 men and women working here, in two 10-hour shifts. They have been awarded the Army-Navy ‘E’ three consecutive times. They cast anxious glances at the gathering clouds in the sky. They don’t want to stop working, and you can’t work in the rain because of the danger of electrocution involved in welding and wiring outdoors.

A minesweeper begins like any other ship – as a blueprint gleam in some engineer’s eye. Each minesweeper is different, you can’t cut them all to the same pattern any more than you can give them all the same name. One may be 180 feet from stem to stern, another 220 feet. But the nursery for them all is the Plate and Angle Shop, where the sheet steel is laid out and cut by the blueprint. This is a great lofty building permeated with the smell of burning metal, where girls and men called angle-smiths work in protective helmets around gas furnaces that are shooting off blue sparks from sheets of steel heated red hot before being shaped as needed. . . .

It is after they are delivered to the Navy, too, that the minesweepers get their names. These show imagination . . .But when the shipyard turns them over to the Navy the minesweeper is known simply by the number. The last one to move down the Savannah River was Hull 13. And with her went the hearty hope of the builders that the 13 will bring plenty of bad luck to the Axis.

By the numbers:

On February 6, 1942 the Maritime Commission announced a contract for the construction of 36 Liberty freighters at the Savannah Shipyards with a base fee of $110, 000 a vessel. There was the opportunity of a bonus of $30,000 per ship, or fine of $50,000, based on speed and efficiency. The original contract for the Savannah Shipyards was 12 freighters.

- “Savannah Yard to Build 36 Ships,” The Atlanta Journal, February 8, 1942, p. 38

Quotation to consider:

“Out of the mud and clay along the south bank of the Savannah River about five miles east of the heart of the city, the shipbuilding plant of the Savannah Shipyards, Inc., is beginning to take form.”

- “Savannah’s Ways Rising Out of Mud,” The Atlanta Journal, July 20, 1941, p. 12

“2 Georgia Labor Filters Supply Dixie Shipyards,” The Atlanta Journal, September 20, 1942, p. 14

Student Activities

Questions for Reading 1 and Photos

- Looking at the map in the photo at the top of the lesson, why was Savannah a prime location for shipyards? Why would Savannah also be a key location for the military and defense efforts?

- What were some of the key features of the new ships being built at the Savannah Shipyards, as described by Crowley?

- What were some of the economic and employment impacts from the shipyards in Savannah?

- Why do you think the shipyard owners and presidents described the purpose and plans for the yards after the war?

“2 Georgia Labor Filters Supply Dixie Shipyards,” The Atlanta Journal, September 20, 1942, p. 14

Questions for Reading 2

- What types and ages of workers were being supplied by the induction centers? Which government agency was involved?

- According to Gilbert C. McLemore, what was the "golden age" for youths entering the induction centers, and why?

- What role do you think the induction centers played in addressing labor shortages and maintaining productivity in essential industries during the war?

“Ocean Broom Factory,” The Atlanta Journal, September 10, 1944, p. 6

Questions for Reading 3

- What were the purpose of minesweepers?

- How many minesweepers had the Savannah Machine and Foundry shipyard built since November 1941? Where had some of these been used?

- What insights does the text provide into the role of women in wartime industries, particularly in jobs traditionally held by men?

- How did the actions of the workers at the shipyard contribute to the broader war effort?

Lesson Closing

How did shipbuilding in Savannah and Chatham County lead to the success of the Allies during World War II?

What were some challenges that had to be overcome in order to meet production demands?

Extension Activity

Private business and corporation owners made financial gains from wartime contracts and production. In some cases, there was corruption and mismanagement. This was the case with the Savannah Shipbuilding, Inc., who built and led operations at one shipyard until a takeover by the Maritime Commission in January 1942.

The two newspaper excerpts share parts of this story.

Excerpt 1

Note: “Get Quick Rich Wallingford” was a fictional con artist who appeared in stories, a 1907 book, and films. Readers at the time would have been familiar with associating this name with being a con artist, or someone that tricks others into believing something untrue, and often financially benefiting from it.

Conditions at Savannah Yard Held ‘Shocking’

Seized Ship Plant to be Tried July 6 For Condemnation

The Atlanta Journal, May 5, 1942, Page 9

. . . Littell said the Government had found that only one of seven executives of Savannah Shipyards, Inc., had had previous experience in shipbuilding, that large fees had been paid for legal counsel in citiies all over the country and that outrageous expenses were charged to the Government. He said one such item was $24,000 for hotels and traveling expenses.

The Government has only begun unraveling the corporate relationships of the Cohen subsidiaries and their maze of finances, he said: Littell described Cohen’s activities as dwarfing the legendary ‘Get Rich Quick Wallingford.’ He said Cohen had run $5,000 initial capital into a corporation which obtained millions in Government shipbuilding contracts.

‘When the Southeastern Shipbuilding Company took over the physical structure of Savannah Shipyards, Inc., in January, shocking conditions were found,’ Littell said.

Launching Held Impossible

‘Competent engineers reported that no ships could ever have been launched from the shipyards as originally built,’ he declared. ‘Built at the mouth of the Savannah River, the construction of the ways was incompetent, floors sagged, the mold loft was poorly constructed and the piling did not have sufficient penetration.’

Littell said the yards were built on felled grounds which couldn't support their weight. Defective machinery was found to have been installed, he added, and the floors were built in such a manner that the steel plates could not be fitted on them. The company is asking $2,187,000 for its property.

Excerpt 2

Shipyard Raps Littell Charges as ‘Unfounded’

‘Trying to Prejudice Public,’ Savannah Plant Counsel Says

The Atlanta Journal, May 6, 1942, P. 16

Answering criticisms against operations of the Savannah Shipyards, Inc., an attorney for the shipyards described as ‘unfounded and misleading’ statements made by Assistant U.S. Attorney General Normal Littell.

Littell, appearing before Federal Judge A. B. Lovett at a hearing here Monday, said that engineers had reported that ‘no ships could ever have been launched from the three ways constructed by the Savannah Shipyards, Inc.”

The shipyards attorney, E. J. Phillips, of Cleveland, Ohio, in a prepared statement Tuesday asserted that if Littell’s criticisms were true ‘then the Maritime Commission should be investigated’ for awarding contracts to the company.

Condemnation proceedings were started against the shipyards after the Maritime Commission cancelled a contract for twelve 10,000 ton ships costing approximately $1,700,000 each. The commission took physical possession of the yards and charged that the company failed to comply with contract stipulations. The contract was given to another shipbuilding concern. . . .

Reflection Questions

- What unethical practices did Littell highlight in his description of Savannah Shipyards, Inc.?

- The shipyards’ attorney said, based on this experience, the Maritime Commission should have been investigated for how they were awarding contracts. Do you agree or disagree, and why?

Note: Savannah Shipyards, Inc., was awarded $1,285,000 as compensation in August 1942 for the yards being taken over by the Maritime Commission.

This lesson was written by Sarah Nestor Lane, an educator and consultant with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

Tags

- american world war ii heritage city program

- world war ii

- wwii

- world war 2

- ww2

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- awwiihc

- shipbuilding

- women in world war ii

- world war ii home front mobilization

- civilian defense

- hour history lessons

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- twhplp

- savannah

- chatham

- georgia

Last updated: October 28, 2024