Last updated: December 27, 2023

Article

Federal Courthouses and Post Offices: Symbols of Pride and Permanence in American Communities (Teaching with Historic Places)

(General Services Administration)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Our Federal Government is the largest builder of buildings ever known in the world…; and the fact that it builds in every part of our great country gives it an unexampled influence upon the architectural art of the entire people. It cannot avoid affecting in a pronounced degree the architectural taste, knowledge, and enjoyment of the nation. It cannot avoid affecting the growth of good architecture in all communities…. The Government, therefore, enjoys in its building operations a tremendous opportunity for good, in the judgment of all who regard architecture as one of the important factors of the higher civilization.1

This statement, made by Treasury Secretary Franklin MacVeagh in 1912, reflects the important role federal buildings have played and continue to play in communities throughout the country. From 1852-1939, the Office of the Supervising Architect of the United States Department of the Treasury was responsible for designing and constructing custom houses, post offices, federal courthouses, and other buildings needed by the federal government. Ranging from modest structures in smaller communities to grand, ornately appointed buildings in large cities, they stood as symbols of the strength and stability of the federal government. Citizens across the country enthusiastically viewed a new federal building as a testament to their city’s prosperity and importance.

Through the years, buildings of the federal government have witnessed significant federal trials, housed the offices of numerous federal agencies, provided space for citizens to conduct business, and served as architectural models for non-federal buildings. Many of the buildings designed under the Office of the Supervising Architect have been meticulously restored by the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) and continue to house the operations of the federal government. Under the care and maintenance of GSA, these historic buildings remain important monuments both to the government of the United States and the communities of which they are a part.

1Annual Report on the State of the Finances, 1912. As cited in Darrell Hevenor Smith, The Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury: Its History, Activities, and Organization (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1923), 30.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the following National Register of Historic Places nomination files: “United States Courthouse, Custom House and Post Office" (with photographs; also known as "Pioneer Courthouse") in Portland, Oregon; “U.S. Post Office and Federal Building” in Denver, Colorado; and “United States Post Office, Court House and Custom House” (with photographs) in Louisville, Kentucky. All three buildings are owned and maintained by GSA. The lesson was written by Brenda K. Olio, former Teaching with Historic Places historian, and edited by staff of the Teaching with Historic Places program and GSA’s Center for Historic Buildings. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, government, civics, and geography courses in units on the growth and role of the federal government, the U.S. court system, federal architecture, urban growth, city planning, and preservation policy.

Time period: Mid-19th to mid-20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Federal Courthouses and Post Offices: Symbols of Pride and Permanence in American Communities relates to the following National history Standards

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

-

Standard 3A: The student understands the issues involved in the creation and ratification of the United States Constitution and the new government it established.

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 2E: The student understands the settlement of the West.

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

-

Standard 1B: The student understands how American life changed during the 1930s.

-

Standard 2A: The student understands the New Deal and the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Federal Courthouses and Post Offices: Symbols of Pride and Permanence in American Communities relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard C – The student explains and gives examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B – The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

-

Standard G – The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

-

Standard H – The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land uses, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard B - The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard B - The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

-

Standard C – The student describes the various forms institutions take and the interactions of people with institutions.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard B - The student describes the purpose of the government and how its powers are acquired.

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard E – The student identifies and describes the basic features of the political system of the United States, and identifies representative leaders.

-

Standard I - The student gives examples and explains how governments attempt to achieve their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution and Consumption

-

Standard D – The student describes a range of examples of the various institutions that make up economic systems such as households, business firms, banks, government agencies, labor unions, and corporations.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard A - The student examines the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

Objectives for students

1) To describe the functions of federal government buildings such as courthouses and post offices and discuss how these buildings impact the communities they serve.

2) To examine federal building design from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century.

3) To explain the role of the U.S. General Services Administration in preserving and managing historic government buildings.

4) To conduct research and prepare presentations on government buildings in their local area and their impact on the community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The lesson can be used in its entirity or in pieces. The map and images appear twice: in a smaller version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) one map of the United States showing locations of the three featured properties;

2) four readings on the federal building program and the featured properties;

3) six photos of the featured properties.

Visiting the site

The U.S. Courthouse, Custom House and Post Office, now known as Pioneer Courthouse, is located on Pioneer Courthouse Square at 700 S.W. Sixth Avenue, Portland, Oregon 97204. For more detailed directions visit the Court Information page of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit website.

The U.S. Post Office and Federal Building, now known as the Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse, is located at 1823 Stout Street, Denver, Colorado 80257.

The U.S. Post Office, Court House and Custom House, now known as the Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House, is located at 601 W. Broadway, Louisville, Kentucky 40202.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Why do you think that?

Setting the Stage

Since its inception, the operations of the federal government have not been limited to the capital city. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gave Congress the authority to establish post offices and post roads as well as forts, arsenals, and “other needful buildings.” These other buildings soon came to include custom houses in port cities to collect duties or taxes on imported goods, marine hospitals to care for the nation’s seamen, and courthouses in the various federal judicial districts to conduct federal trials. By the mid-19th century, the increasing need for such buildings throughout the country led to the creation of a unified federal building program. The Office of the Supervising Architect, placed under the administration of the Department of the Treasury, was responsible for designing custom houses, courthouses, post offices, and other government buildings from 1852-1939. These buildings stood as visible representations of the strength and stability of the federal government and thus the nation as a whole. Reflecting the latest architectural trends, they often served as models for non-federal buildings and inspired civic pride in towns and cities across the nation.

Many of the buildings constructed under the Office of the Supervising Architect are still in use by the federal government today. These historic buildings are part of a huge inventory of federal buildings maintained by the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA). GSA was established in 1949 to help manage and support the basic operations of the federal government. GSA's Public Buildings Service (PBS) is responsible for providing workplaces for federal agencies throughout the country. This task involves constructing new buildings as well as renovating existing buildings to accommodate approximately one million federal employees in more than 2,000 communities across the nation. By restoring and continuing to use historic government buildings, GSA is ensuring the legacy of the federal building program.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Location of three historic General Services Administration buildings

(General Services Administration)

As of 2008, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) owned approximately 1,600 buildings across the country. Almost 300 of those 1,600 properties have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The National Register is the nation’s official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects worthy of preservation. Listed properties are valued for their significance in American history, architecture, archeology, engineering, and culture. GSA’s properties listed in the National Register range from modest 19th-century custom houses to grand turn-of-the-century classical buildings to stately Depression-era buildings. Three of GSA’s historic buildings are the Pioneer Courthouse in Portland, Oregon (1869-75); the Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse in Denver, Colorado (1910-16); and the Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House in Louisville, Kentucky (1931-32). These buildings continue to house the offices of the federal government and still serve important roles in their communities.

Questions for Map 1

1. Based on information found in Setting the Stage, what are some of the functions that federal buildings were and are built to house? Why would these buildings need to be located in cities and towns throughout the country as opposed to only in the nation’s capital?

2. Why might so many of GSA’s historic buildings be considered important enough for listing in the National Register of Historic Places?

3. Locate the three buildings. In what part of the country is each building located? When was each structure built? What do the official names of the buildings indicate about their use?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Federal Building Program

In its earliest years, the federal government typically rented space in existing buildings to conduct business outside of the capital city. In the first decades of the 19th century, however, the federal government began constructing more buildings to house its operations. Such buildings included custom houses in port cities and marine hospitals for the nation’s seamen. Since the Department of the Treasury collected custom duties and administered the hospital fund for seamen, it naturally assumed responsibility for constructing the buildings to house these operations. Many custom houses built during this period reflected the popular Greek Revival style of architecture. This style reflects design elements found on ancient Greek temples such as the Parthenon to suggest democratic principles.

The Department of the Treasury’s role soon grew to include the construction of other government buildings such as post offices and courthouses for the federal courts. The Judiciary Act of 1789 had established a three-tiered federal judicial system: 1) 13 district courts (defined by state boundaries), 2) three larger circuit courts (Eastern, Middle, and Southern), and 3) a Supreme Court. These federal courts decided disputes involving rights and liberties guaranteed by the Constitution. The Supreme Court, the highest court in the nation, convened in Washington, D.C., and mainly heard cases appealed from the lower courts. The district and circuit courts handled federal civil and criminal cases and met in the judicial districts located throughout the country. As more states joined the Union, the number of judicial districts increased along with the need for federal courthouses within these districts.

The expansion of the federal government, and the nation’s urban areas, in the 1850s led to the need for more custom houses, post offices, and federal courthouses across the nation. In 1852, the Secretary of the Treasury established the Bureau of Construction to help manage and unify this growing federal building program. By the end of that year, Ammi B. Young had become the first government architect to be referred to as “Supervising Architect.” Eventually, the Bureau of Construction came to be called the Supervising Architect’s Office or the Office of the Supervising Architect. Young remained the head designer for all federal buildings under the Treasury Department until 1861 when building projects stopped due to the Civil War.

Following the Civil War, the Supervising Architect’s Office began designing more elaborate federal buildings. These buildings were meant not only to house government offices, but also to symbolize the power and stability of the federal government. Alfred B. Mullett became Supervising Architect in 1866 and helped bring attention to the federal building program. Ornate new government buildings in major cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia called to mind the prosperity of the nation. Mullet designed many of these impressive buildings in the grand Second Empire style, a style based on French architecture during the reign of Emperor Napoleon III (1852-1870).

Mullett and his staff also designed federal buildings for many smaller cities such as Raleigh, North Carolina, and Madison, Wisconsin. These buildings often followed standard plans, but still reflected the architectural character of their particular region. Mullett said, “In the preparation of plans, I have been governed by the requirements of the various branches of the public business at each locality, and while avoiding any unnecessary expense or display, I have endeavored to render each building ample for the proper accommodation of the officers for whose use it was intended, and at the same time convenient, durable, and credible to the government."1 Because custom houses and federal courthouses usually were needed in growing urban centers, their construction was seen as a statement of that city’s importance and potential for future prosperity. To the citizens of these cities, federal buildings represented the “latest in architectural style and technology and, symbolically, membership in the Union."2 As symbols of stability, such buildings inspired confidence in the federal government.

The financial panic of 1873 and the depression that followed caused a big change in the federal building program. Second Empire style buildings seemed overly grand and expensive for the hard economic times. The less decorative Romanesque Revival style--characterized by massive, rough-textured stone walls, rounded arches, and square towers--became popular for federal buildings of the 1880s. The federal government continued to expand during this period, and the number of federal employees reached more than 150,000 by the end of the decade. By 1892, the Office of the Supervising Architect maintained almost 300 buildings with nearly 100 more under construction. The Supervising Architect’s Office continued to construct Romanesque Revival style buildings well into the 1890s.

Meanwhile, private architects called for a new style of federal architecture that would reflect the country’s emerging status as a world leader. The American Institute of Architects had argued for years that buildings designed under the Supervising Architect were inferior in design and cost more than buildings by private architects. Missouri Congressman John C. Tarsney agreed with this stance and introduced a bill to allow public buildings to be designed by private architects through design competitions. The Tarsney Act passed in February 1893.

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, staged to honor the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage to America, had a huge impact on public architecture. Most of the nearly 200 buildings constructed to house the exhibits were designed in a style known as Beaux Arts. This style of architecture was taught at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris and was based on the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome. In America, Beaux Arts was part of a broader architectural style referred to as Neoclassicism or Classical Revival. The millions of people who visited the fair were dazzled by the gleaming grandeur of what was called the “White City.” The grand scale, symmetry, elaborate ornamentation, and classical details of these buildings soon influenced the design of federal buildings. Many people now considered Romanesque Revival style buildings to be out-of-date.

James Knox Taylor became Supervising Architect in October 1897. Federal buildings during his tenure embraced the classical style and boasted monumental entrances and grand public lobbies to welcome citizens to the offices of the federal government. Facades were typically covered in white limestone or marble and featured classical details such as columns. This style was fitting as it called to mind the great democracies of Greece and Rome and “bespoke the power, influence, and self assurance of a nation on the brink of world leadership."3

In August 1912, Congress repealed the Tarsney Act. Only about 30 of more than 400 buildings had been designed according to its provisions. The act benefited a few private architectural firms, but the federal government still had to employ a large number of architects in the Supervising Architect’s Office. By 1913, the Supervising Architect’s Office had 253 employees in Washington and 103 in the field.4 Classical architecture was well established as the most common style for public buildings. Treasury Secretary Franklin MacVeagh stated: “Our Federal Government is the largest builder of buildings ever known in the world…; and the fact that it builds in every part of our great country gives it an unexampled influence upon the architectural art of the entire people…. The Government, therefore, enjoys in its building operations a tremendous opportunity for good, in the judgment of all who regard architecture as one of the important factors of the higher civilization."5

World War I halted the federal building program temporarily, but business returned to normal in the years following the war. By 1930, however, the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression gripped the country. The purpose of the federal building program shifted as it became a tool to provide jobs to out-of-work construction workers, artists, and others. In 1933, as part of a government reorganization under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Supervising Architect’s Office was renamed the Public Works Branch. In 1939, as the nation began focusing on preparations for war, the Public Works Branch was taken out of the Treasury Department and became part of the new Federal Works Agency. During World War II, the Federal Works Agency focused on meeting wartime demands for temporary office space, hospitals, and dormitories.

In 1948, President Harry Truman appointed a commission to report on ways to improve the process for supplying federal agencies with workspace, goods, and services. As a result of the commission’s findings, Truman established the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) in 1949. The functions of the Federal Works Agency were placed under GSA’s Public Buildings Service (PBS). Eventually, it was decided that all PBS projects would be designed by private architects. In the 1950s, the title Supervising Architect became "assistant commissioner" for design and construction. Today the position is referred to as Chief Architect.

GSA’s Public Buildings Service took over responsibility for federal workspaces, including many historic buildings that served as courthouses, custom houses, and post offices. (The U.S. Postal Service manages many historic buildings that were designed and functioned specifically as post offices.) In 1976, Congress passed legislation encouraging GSA to utilize space in these older federal buildings. This set the tone for GSA’s efforts to preserve the character of historic buildings while ensuring that they meet the modern needs of the federal government. By preserving and continuing to use historic federal buildings, GSA upholds the proud tradition of the federal building program and provides citizens with a tangible reminder of their community’s past.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why did the Treasury Department assume responsibility for the federal building program?

2. What types of buildings did the Supervising Architect’s Office design and build? Why were these buildings necessary? What other roles did these buildings serve aside from providing space for government operations?

3. Describe some of the architectural styles used by the Supervising Architect’s Office and explain why each was deemed appropriate for government buildings at the time.

4. How would you paraphrase the Treasury Secretary MacVeagh’s quote about the impact of the department’s building program?

5. When and why was GSA established? What is the role of the Public Buildings Service?

6. Do you think it is important to preserve and utilize historic federal buildings? Explain your answer.

Reading 1 was adapted from Lois Craig, The Federal Presence: Architecture, Politics, and Symbols in United States Government Building (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1978); Antoinette J. Lee, Architects to the Nation: The Rise and Decline of the Supervising Architect’s Office (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Darrell Hevenor Smith, The Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury: Its History, Activities, and Organization (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1923); U.S. General Services Administration, Re-Dedication of the Pioneer Courthouse [Brochure] (Portland, Oregon, 2005); and U.S. General Services Administration, “Historic Buildings,”

1U.S. General Services Administration, Re-Dedication of the Pioneer Courthouse [Brochure] (Portland, Oregon, 2005).

2Lois Craig, The Federal Presence: Architecture, Politics, and Symbols in United States Government Building (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1978), 163.

3Antoinette J. Lee, Architects to the Nation: The Rise and Decline of the Supervising Architect’s Office (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 9.

4 Lois Craig, The Federal Presence, 99.

5Annual Report on the State of the Finances, 1912. As cited in Darrell Hevenor Smith, The Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury: Its History, Activities, and Organization (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1923), 30.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The Pioneer Courthouse in Portland, Oregon

Portland, Oregon, was established in 1845 along the west bank of the Willamette River. By the time Portland was incorporated in 1851, it had more than 800 inhabitants. In 1859—the year Oregon gained statehood—Matthew Paul Deady became the first U.S. District judge for the newly-created federal judicial district of Oregon. Deady first convened the federal court in Oregon’s capital city of Salem, but he moved the court to Portland in 1860. During this period, many towns in the Pacific Northwest hoped to demonstrate their prosperity and permanence by obtaining a federal courthouse or custom house. A notable public building could bring attention and prestige to a growing town. As the major port of the Pacific Northwest and the seat of the federal district court, Portland was a natural location for such a building. In 1869, the U.S. government purchased a block of land from the city for $15,000 for construction of a building that would house all offices and services of the federal government in Portland.

Supervising Architect Alfred B. Mullett designed Portland’s federal building in the Italianate style. Inspired by Italian Renaissance villas, this style was typical of civic and government buildings in San Francisco and Portland during this period. Completed in 1875, the three-story, rectangular, stone building cost $396,500, an enormous amount of money at the time. Articles touting the impressive new federal building appeared in newspapers and magazines throughout the West. Its symmetrical design featured classical Italian elements such as pilasters (flat columns attached to a wall) and an octagonal wood cupola (small dome-shaped structure) on the roof. The U.S. Post Office occupied the first floor and the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon was located on the second floor. Other offices included the U.S. Customs Service and the Bureau of Internal Revenue (now the Internal Revenue Service, or IRS).

Mullet designed the federal building for a community that had fewer than 15,000 citizens. By 1889, Portland’s population had quadrupled, and this structure could no longer meet the city’s needs. Even after the Bureau of Internal Revenue moved out of the building, the U.S. Post Office still did not have enough space to operate efficiently. At the time, Portland’s bustling post office was open seven days a week and produced more revenue for the federal government than any other post office in the country.1 In June 1902, Congress approved $200,000 for remodeling and expanding the building. The project, carried out between 1903 and 1905 under Mullett’s successor James Knox Taylor, doubled the size of the first floor and basement and created two wings at the second and third floors. The additions closely matched the style of the original structure. On the interior, the use of steel I-beams, cast iron columns, and new electrical and heating systems modernized the structure.

During this period, many of the federal court cases for the District of Oregon involved disputes over mining claims as miners came to Oregon and nearby states searching for gold, silver, and other mineral resources. Between 1903 and 1906, several important trials for timber and land fraud took place in the building. Federal investigations found that land speculators and timber companies had illegally obtained large areas of public land with the assistance of public officials. The Oregon Land Fraud Scandal resulted in the indictments of some of Oregon’s most prominent politicians, including Senator John H. Mitchell and Representative John Williamson.

In 1933, the U.S. Post Office and the U.S. District Court moved to new quarters. The federal building reopened in 1937 as a branch postal station and was renamed the Pioneer Post Office. In 1939, Congress authorized demolition of the building when it could not find a buyer. Congress never appropriated funds for the demolition, however, and the courthouse remained standing. During World War II, the government used the structure for military offices. In the 1950s, the building remained empty while heated debate ensued over its fate.

During the late 1950s and 1960s, many of Oregon’s citizens and public figures—including Congresswoman Edith Green, Senator Mark Hatfield, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Richard Chambers, and District Court Judge John Kilkenny—worked to save the building from demolition. In 1969, the federal government finally authorized restoration of the building to accommodate a post office branch station and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Congress had established the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 1891 to hear appeals of decisions made by the U.S. district courts in California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. Today, the Ninth Circuit has expanded to include nine states and the U.S. territories of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.

Between 1969 and 1973, GSA undertook a major exterior and interior rehabilitation project to prepare for the new tenants. Work included creating a new central corridor and post office lobby and replacing materials that were not original to the main lobby with windows, doors, and paneling to match the original finishes. GSA also modified second and third floor offices to create hearing rooms and space for judges and clerical staff. In 1973, the building was renamed Pioneer Courthouse and listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Four years later, the Secretary of the Interior designated Pioneer Courthouse a National Historic Landmark (NHL). To become an NHL, a building must “possess exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States."2 In 2002, more restoration and rehabilitation took place to modernize systems.

The efforts to preserve Pioneer Courthouse have resulted in it being the oldest standing federal building in the Pacific Northwest and the second oldest federal courthouse west of the Mississippi. Over the years, the building has welcomed many visiting presidents, provided a place for countless citizens to conduct business, and witnessed important trials such as the Oregon Land Fraud trials. Today, GSA continues to manage the Pioneer Courthouse and aims to “encourage public visitation, enhance and celebrate appreciation of the Courthouse, promote understanding of its historical and architectural significance and evolution, and increase its visibility and image as a prominent federal public building.”3

Questions for Reading 2

1. What architectural style did Mullett choose for Portland’s federal building? Why would this choice have been considered appropriate?

2. Give a brief history of the building’s use over time. Who occupies the building today?

3. Why did the building need to be altered at the beginning of the 20th century? What did this say about Portland’s continued growth?

4. When and for what purpose was the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit established?

5. What do you think would have happened if citizens and public officials had not argued for the building’s continued use? Do you think the loss of such a building would have impacted the community? Explain your answer.

Reading 2 was adapted from Carolyn Pitts, “United States Courthouse, Custom House and Post Office” (Multnomah County, Oregon) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1977; U.S. General Services Administration, Re-Dedication of the Pioneer Courthouse [Brochure] (Portland, Oregon, 2005); U.S. General Services Administration, Pioneer Courthouse [Brochure] (GSA, n.d.); and U.S. General Services Administration, At the Forefront of Adventure and Architecture: Pioneer Courthouse [Video Recording].

1U.S. General Services Administration, Re-Dedication of the Pioneer Courthouse [Brochure] (Portland, Oregon, 2005).

2National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Servic.

3U.S. General Services Administration, Re-Dedication of the Pioneer Courthouse [Brochure] (Portland, Oregon, 2005).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse in Denver, Colorado

A group of prospectors founded Denver on November 22, 1858, after discovering gold at the confluence of Cherry Creek and the South Platte River in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. This area was part of Kansas Territory at the time, and the group named the new town for the Governor of Kansas Territory, James W. Denver. In 1859, the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush drew roughly 100,000 people to the region. The increase in population led the federal government to establish Colorado Territory in 1861. Denver, which had become a mining supply town, was named the territorial capital in 1865. On August 1, 1876, Denver became the state capital when Colorado was admitted to the Union as the 38th state.

In 1870, Denver citizens financed construction of a railroad that connected Denver to the transcontinental line in Wyoming. This action ensured that Denver would remain viable when many other mining towns went bust. In fact, Denver’s population grew from less than 5,000 to more than 100,000 between 1870 and 1890. The discovery of silver in the 1880s brought more prosperity to the city. When the silver panic of 1893 threatened Denver's economy, the city changed its focus and became an important center for livestock sales and agriculture. By 1900, Denver was a major transportation crossroads and second only to San Francisco as the largest city west of Omaha, Nebraska. However, the city still reflected the dusty, unplanned character of many boom towns.

In 1904, Robert Speer became Denver’s new mayor and set out to transform the city. He had visited the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and been impressed with the fair’s orderly and grand layout. He began an extensive effort to organize and beautify Denver with planned boulevards, parks, and new buildings that would reflect Denver’s permanence. Denver’s U.S. Post Office, which had been built in 1893, was considered too small and outdated to meet the growing city’s needs by this time. The Denver Chamber of Commerce petitioned Congress in 1904 for a new federal building. The petition argued that the old federal building was insignificant compared with surrounding structures and compared to the “more pretentious” federal building in Pueblo, Colorado.1 The people of Denver wanted a federal building more suitable for a growing metropolis.

In 1908, Congress finally appropriated the necessary funds, and a site for a new building to house all federal agencies in Denver was purchased. James Knox Taylor served as Supervising Architect of the Treasury during this time. Under the provisions of the Tarsney Act, Taylor selected the New York architectural firm Tracy, Swartwout, and Litchfield to design the building. It was the largest building project ever undertaken in Denver, and citizens were enthusiastic as construction began in 1910. The $1,500,000 appropriation was not enough, however, and an additional $400,000 was necessary to complete the project. In January 1916, the federal government finally occupied the new facility.

Denver’s new federal building was designed in the Neoclassical or Classical Revival style of architecture. This style, which dominated federal building design at the time, helped bring design elements popular in the eastern United States to newer western cities such as Denver. Characteristics of the style included a symmetrical design, classical details such as columns, and a grand scale. Denver’s monumental, four-story, marble building took up an entire city block in downtown. The main entrance facade featured 16 three-story columns. On the interior, the impressive main lobby spanned the width of the building. The U.S. Post Office occupied most of the first floor. The second floor included space for the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, and a law library. Other federal agencies such as the Immigration Department and the Bureau of Internal Revenue occupied the third and fourth floors. The building’s monumental scale and elegant design was deemed an appropriate expression of the city’s importance and served as inspiration for other civic buildings in the city.

The federal building also boasted notable artwork. A New York artist designed four canvas murals for the lobby in 1918. In 1936, Denver artist Gladys Caldwell Fisher added two limestone sculptures of Rocky Mountain sheep at one of the entrances. The Depression-era Treasury Relief Art Program (TRAP) funded this project. TRAP was established in 1935 with a $530,000 grant to the Treasury Department from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The program, part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, was designed to provide relief for unemployed painters and sculptors by hiring them to create art in new and existing federal buildings nationwide.

In the years following World War II, Denver’s population expanded rapidly as more federal agencies moved to the city. Despite undergoing major interior changes, the building was not able to keep up with the office space needs of the federal government in Denver. In 1965, the U.S. District Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit moved to a new courthouse. The old building came to be used almost entirely by the U.S. Post Office. To accommodate its needs, the Post Office changed the lobby, demolished the appellate courtroom and grand jury room, and expanded the third floor.

The building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. By the late 1980s, decades of remodeling had destroyed much of the grandeur of the original structure. Around this time, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit again was in need of a new facility. Rather than construct a new courthouse, GSA decided to undertake a major renovation of the old federal building. In 1991, GSA closed the building to begin the $28 million renovation. GSA was able to reverse many of the earlier alterations while making the building suitable for the court. GSA reconstructed the appellate courtroom and the grand jury room as well as restored the former post office lobby for use as a public gallery. In 1994, the building was rededicated as the Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse to honor a prominent Colorado lawyer who served on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 to 1993. The building has won several preservation awards including the Presidential Award for Design Excellence in 1997.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Give a brief synopsis of Denver’s history from its founding to the turn of the 20th century. What are some of the reasons Denver became and stayed a successful town?

2. Why did the Chamber of Commerce petition Congress for a new federal building?

3. What was the Tarsney Act? (Refer to Reading 1 if necessary.) How did this act affect Denver’s federal building?

4. What was TRAP? Why do you think this program would have been important to federal building projects?

5. Describe the Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse. How did the building and its uses change over time? Why did these changes occur?

Reading 3 was adapted from Susan A. Nieminen, “U.S. Post Office and Federal Building” (Denver County, Colorado) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1972); U.S. General Services Administration, Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse [Brochure] (GSA, n.d.); and U.S. General Services Administration, A Poem in Marble, a Place on the Map: The Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse [Video Recording].

1Susan A. Nieminen, “U.S. Post Office and Federal Building” (Denver County, Colorado) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1972), section 8, page 1.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: The Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House in Louisville, Kentucky

In 1926, Congress passed the Public Buildings Act, which set the stage for a huge increase in the federal building program. Under the act, Congress appropriated $165,000,000 for public buildings in 85 cities across the country.1 One of these cities--Louisville, Kentucky--received funds for a new post office and federal building to replace an existing federal building from 1858. The 1920s was a prosperous decade for the city. Louisville was the largest city in Kentucky at the time and played an important role in the regional manufacturing and shipping industries. Located on the Kentucky-Indiana border along the falls of the Ohio River, the city was a major shipping port. Population growth, a boom in new manufacturing industries, and major new construction in the downtown area reflected the city’s prosperity. The need for a new federal building was another important indication of Louisville’s prominence.

By November 1929, a site along Broadway between Sixth and Seventh Streets had been secured. This area had recently become the commercial center of the city as building activity moved further away from the river. Dozens of houses and small stores had to be demolished to make way for the massive new structure. Construction took place from 1931 to 1932 under Acting Supervising Architect of the Treasury James A. Wetmore. The Post Office, Court House and Custom House was officially dedicated in January 1933. By the time of its completion, however, the Depression had all but ended the city’s rapid growth. The structure was one of only two building projects in Louisville during the early 1930s. The completion of the $3 million federal building signified Louisville’s perseverance in a time of economic hardship.

Wetmore designed Louisville’s new federal building in the Neoclassical or Classical Revival style, still the most common style for federal architecture in the 1930s. The five-story structure spanned an entire city block and featured a limestone facade over modern materials such as concrete and steel columns and beams. The wide main lobby spanned the length of the building and included brass and glass postal boxes and windows as well as free-standing brass tables to serve post office patrons. As the primary public space, the lobby was ornately finished with marble floors, baseboards, and walls. Main rooms on the second floor included a law library and two courtrooms for hearing cases of the U.S. District Court for the District of Western Kentucky.

Between 1935 and 1937, Kentucky-born artist Frank Weathers Long painted 10 murals for the lobby walls depicting regional themes of commerce, agriculture, and sport. The murals were among the first commissioned by the Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP)—a Depression-era relief program designed to give work to unemployed painters and sculptors while providing federal buildings nationwide with artwork. The four largest murals, titled Stock Farming, Agriculture, Ohio River Traffic, and Coal Mining, measure approximately 23 feet in length by 3 feet in height. Smaller murals depict horse racing scenes and postal delivery. In 1936, the Public Works Administration (PWA) funded the addition of a sixth floor to provide more space for offices and courtrooms. This massive project involved removing the 2.5 million-pound roof and using 600 jacks to raise it 11 feet.

In the 1950s, the building underwent interior renovations to update some features and to repair damage from a fire in the attic. In 1986, the Postal Service moved out, and GSA undertook a $22 million, four-year renovation project to modernize the building and restore the public lobby and second floor courtrooms to their 1932 appearance. The name of the building was changed to the Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House in 1986 to honor Congressman Marion Gene Snyder, a prominent figure in Kentucky politics. As a result of the renovation, the building received numerous awards, including the 1999-2000 International Award for Government Building of the Year, Historic Building Category, from the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA). The building, considered one of Louisville’s best examples of the Neoclassical style, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. Housing the U.S. District Court and the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Western Kentucky as well as several other federal agencies, the Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House continues to play a vital role in the community today while serving as a proud link to Louisville’s past.

Questions for Reading 4

1. How did the Public Buildings Act impact Louisville?

2. How would you describe Louisville in the 1920s? Why did this change in the 1930s?

3. Why would the construction of the federal building have been seen as a symbol of hope during this period?

4. Describe the murals. How were they commissioned? How do they reflect Kentucky’s heritage?

5. Why did GSA modernize the building? What types of changes do you think might have been necessary to make a 1930s building suitable for modern use?

Reading 4 was adapted from Philip Thomason, “United States Post Office, Court House and Custom House” (Jefferson County, Kentucky) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1999; U.S. General Services Administration, Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House [Brochure] (GSA, n.d.); and U.S. General Services Administration, An American Classic: Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House [Video Recording].

1Philip Thomason, “United States Post Office, Court House and Custom House” (Jefferson County, Kentucky) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1999), section 8, page 8.

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: U.S. Courthouse, Custom House and Post Office (now Pioneer Courthouse), Portland, Oregon, ca. 1877

(General Services Administration)

This image was taken from the five-story tower of Portland’s first high school about two years after the federal building’s completion. When the government purchased land for the new federal building in 1869, citizens criticized the site because it was several blocks from what was then the commercial center of Portland on the banks of the Willamette River. However, when fires destroyed areas of the downtown in 1872 and 1873, businesses began relocating away from the river, and thus closer to the site of the federal building.

As shown here, the original building (before the 1903-5 expansion) measures 118 feet by 66 feet and features a rectangular plan with a symmetrical exterior. The building is wood frame construction faced with sandstone. Each facade of the Italianate structure has a projecting central bay topped by a classical pediment (triangular section formed by a low-pitched gable roof). Pilasters (flat columns attached to a wall) line the second and third stories of the exterior. An octagonal wood cupola (small dome-shaped structure) with arched windows crowns the roof. Later additions increased the size of the building, but closely followed the original style.

Questions for Photo 1

1. Study the photograph carefully. How would you describe Portland during this time period?

2. Why was the location criticized at first? Why did the commercial center of town shift by the time the courthouse was completed?

3. What does the photo indicate about the importance of the new federal building? Based on the written description, try to identify some of the building’s architectural features. Click here for a drawing to help you identify architectural features.

4. What functions were housed in the building when it first opened? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary.)

Visual Evidence

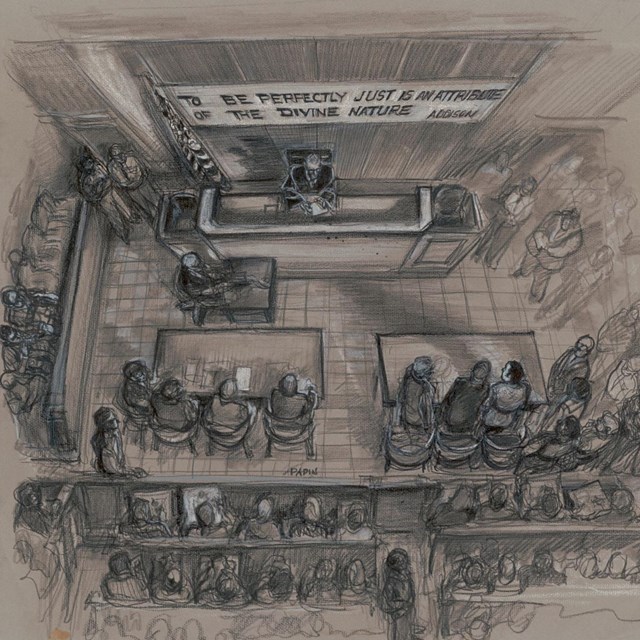

Photo 2: Courtroom, Pioneer Courthouse today

(General Services Administration)

The U.S. court system consists of 94 judicial districts, including one or more in each state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and overseas territories. These judicial districts are arranged into 12 regional circuits, each of which has a court of appeals. These circuit appellate courts are one step below the U.S. Supreme Court. Since 1973, Pioneer Courthouse has been one of four primary locations where the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit hears appeals.

This two-story courtroom in the Pioneer Courthouse is located on the second floor of the building. It features pilasters, original wood trim and molding, and an ornamented ceiling. During the 1970s restoration, Ninth Circuit Judges Richard Chambers and John Kilkenny acquired lamps, counsel tables, chairs, benches and other historic items from several federal courthouses to furnish the courtroom and other public spaces in the building.

Questions for Photo 2

1. What types of cases were originally heard in this courtroom? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary.) What types of cases would be heard here today?

2. How did the building become home to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary.) Do you think this was an appropriate reuse for the building? Explain your answer.

3. Why do you think Judges Chambers and Kilkenny took the actions described above? Based on the photo, do you think their efforts made a significant contribution to the courtroom? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: U.S. Post Office and Federal Building (now Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse), Denver, Colorado, August 1914

(General Services Administration.)

Denver’s federal building, which takes up an entire city block, is clad in Colorado Yule marble. Classical features include a symmetrical design, low-pitched roof, huge columns on the main facade, engaged columns (columns attached to a wall) on the remaining sides, and a large entablature (a series of horizontal bands directly above a set of columns). Above the main entrance, the entablature includes names of several cities to the east and west of Denver, symbolizing the flow of mail across the country. Other sides of the building feature Latin phrases that translate "The law causes wrong or injury to no one" and "To no one shall we deny justice, nor shall we discriminate in its application."

Questions for Photo 3

1. Based on Reading 3, how do you think this building would have related to developments in Denver in the early 20th century? How do you think the citizens of Denver would have reacted to a new federal building that looked like this?

2. What can you tell about building methods, etc. of the time period by studying this photo?

3. Based on the written description, try to identify some of the building’s classical features. Click here for a drawing to help you identify architectural features.

4. Do you think the decorative details on this building are important? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Courtroom, Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse today

(General Services Administration)

Today, the Byron R. White Courthouse is used by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit hears appeals from cases tried within all the district courts located in the Tenth Circuit, including those in Colorado, Oklahoma, Utah, Wyoming, Kansas, and New Mexico. This room served as the law library when the building was first constructed. During the renovation in the early 1990s, GSA restored the library and also converted the room into a small courtroom.

Questions for Photo 4

1. Describe the room shown in Photo 4. What clues can you find that tell you what its original use was? Why would this kind of room have been an important part of the courthouse?

2. What clues in this photo indicate how the room is used today? Do you think this was an appropriate reuse of the room? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: U.S. Post Office, Court House and Custom House (now Gene Snyder U.S. Court House and Custom House), Louisville, Kentucky, ca. 1935

(General Services Administration)

This building was inspired by the architecture of the U.S. Treasury Department Building, constructed in Washington, D.C., in the mid 19th century. Unlike the solid masonry construction of the Treasury Department Building, Louisville’s federal building featured modern materials such as concrete and steel columns and beams under a limestone facade. The main facade has 18 engaged columns (columns attached to a wall), a rusticated (made up of stone blocks separated by deep horizontal grooves) ground floor with arched windows, and projecting pavilions (sections of a building) with free-standing columns and a pediment (triangular section formed by a low-pitched gable roof) at each end.

Questions for Photo 5

1. What was happening in the country while this building was under construction? (Refer to Reading 4 if necessary.) Why was the completion of a building like this important to the citizens of Louisville?

2. Based on the written description, try to identify some of the building’s architectural features. Click here for a drawing to help you identify architectural features.

3. Can you identify the types of activities that would have taken place in this building when it was constructed? Which of these activities still take place in the building today? (Refer to Reading 4 if necessary.)

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Post Office lobby, U.S. Post Office, Court House and Custom House (now Gene Snyder U.S. Courthouse and Custom House), November 1932

(General Services Administration)

This photo was taken a couple of weeks before the post office officially opened for business in November 1932. The lobby was originally designed as a grand public space to serve post office customers. It extends the length of the building and features pink, green, and beige marble flooring and marble walls. The postal windows have marble counters and brass grilles, and customer postal boxes are made of glass and brass. Decorative bronze leaves and arched brass grilles above the postal windows and boxes add to the gleaming decor. Brass writing tables line the center of the lobby. Although this lobby no longer functions as a post office, its appearance remains much as it did in the 1930s.

Questions for Photo 6

1. Does this photo look like the inside of any buildings in your community? If so, what are the buildings used for?

2. Based on the written description, identify as many features in the photo as possible.

3. Do you think it was important to preserve the original features of this space even though it is no longer used as a post office? Explain your answer.

Putting It All Together

In Federal Courthouses and Post Offices: Symbols of Pride and Permanence in American Communities, students have examined federal services in three American cities and the role of the General Services Administration in constructing and maintaining the buildings that house those services. The following activities will help students better understand the operation of the U.S. court system and also consider what different building functions tell us about how a community’s needs change over the course of its history and how government adapts to those changes.

Activity 1: The Federal Judicial System

Ask students to conduct research and then make a chart describing the different branches of the U.S. court system (U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. District Courts, and U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals). The chart should explain briefly when and how each type of court was created, the types of cases heard by each court, where they operate, the number of judges for each, and the procedure for selecting judges. Next, ask students to gather information about their state’s court system and compare the federal and state judicial systems in terms of types of cases heard, how judges are selected, etc. Conclude the activity by discussing as a class why it is important to have federal courthouses throughout the country.

Activity 2: What If . . .

Divide students into small groups and ask each group to find and conduct research on a federal, state, or county building (a courthouse, post office, general government building) in their area. At least one of the groups should first consult GSA’s Historic Buildings Database to find out if there is a GSA building in their community. Direct each group to prepare a visual presentation such as a poster or exhibit that describes the building itself, its use over time, and how the building functions in the community. If possible, have the groups include photographs of the community at the time the government building was erected. Students should then try to assess the impact of the building on the community at the time and compare that to how the building fits into the physical fabric of the community today. If the building is historic, students should determine if it has earned any designations at the local, state, or national level. After each group has made its presentation, conclude the activity by discussing how the activities housed in these various buildings impact life in their community. Arrange to have the posters or exhibits displayed at the local library or historical society.

Supplementary Resources

The General Services Administration (GSA)

GSA’s Historic Buildings web pages offer options to research architectural styles that influenced America’s public buildings, study a timeline to learn the role that public buildings have played in the development of the United States, and search by state to discover architecturally and historically significant buildings throughout the country.

National Park Service, Heritage Education Services

The Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) website contains more than 130 curriculum-based lesson plans on places listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Federal Judicial Center

The Federal Judicial Center was established by Congress in 1967 as the education and research agency of the federal courts. The Center’s History of the Federal Judiciary web pages include detailed explanations of the federal courts, a timeline of landmark judicial legislation, biographies of federal judges, and an inventory of historic federal courthouses.

U.S. Courts

This website is maintained by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts and is designed as a clearinghouse for information from and about the Judicial Branch of the U.S. Government. Visit the site for information on the U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. District Courts, U.S. Courts of Appeal, and U.S. Bankruptcy Courts.

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

The Judicial System

The Judicial SystemHow does the judicial system work? What is a federal court? Why are people trying to reclassify certain offenses?

-

Federalism

FederalismWhat is federalism? How have some Americans used debates about federalism to promote segregation?

-

Teaching Engaged Citizenship

Teaching Engaged CitizenshipUse these mini-lessons to fit civics education into a variety of social studies classrooms.

Tags

- federal courthouse

- oregon

- oregon history

- colorado

- colorado history

- kentucky

- kentucky history

- architecture

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- mid 19th century

- gilded age

- early 20th century

- civics

- shaping the political landscape

- art and education

- twhplp