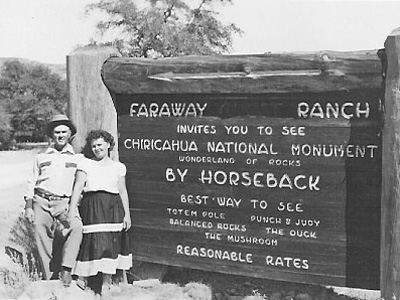

Guests at Faraway also enjoyed excursions into the area that Lillian called a “Wonderland of Rocks.” Here, spires and pinnacles of rock clustered together, forming fantastic geologic formations.

A volcanic eruption twenty-seven million years before had left behind layers of pumice and ash two thousand feet high. The ash and pumice fused together to create a rock called rhyolitic tuff. Over time, the rhyolite weathered into a maze of rock columns. The Chiricahua Apaches called the area “The Land of Standing-Up Rocks,” but surprisingly few Anglo-Americans knew of the area until the twentieth century. Lillian’s father had stumbled upon the formations, but it wasn’t until 1921 that Ed and Lillian began an extensive exploration of the area. They quickly realized the commercial potential inherent in the dramatic scenery and hired an amateur photographer to take several panoramic photos. Ed and Lillian sent the photos to the county fair and to the chambers of commerce of several local towns.

The photographs aroused interest in the rock formations, and soon a grassroots movement developed to have the area officially preserved. The Antiquities Act, passed in 1906, allowed the president to set aside areas of “historic or scientific interest.” Numerous national monuments, including Casa Grande, Chaco Canyon, and Tumacácori already existed in the Southwest. By the 1920s, the national monuments were becoming popular tourist attractions, particularly as the rise in automobile ownership allowed more people to reach the monuments, often located in isolated areas. When the governor of Arizona, George W. P. Hunt, visited the “Wonderland of Rocks” in 1923, he supported the creation of a national monument. On April 18, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the legislation creating Chiricahua National Monument.

NPS

As the only facility in the area that offered lodging and meals to visitors, Ed and Lillian had strong financial motivations for wanting the monument created. Lillian always included mention of the monument in promotional literature for the ranch. After 1924, business at Faraway increased and their clientele expanded, with visitors from New York, California, and many other states. Although the legislation creating national parks and monuments rarely mentioned tourism directly, attracting visitors and boosting local economies became a strong argument in favor of preservation. The tourism industry was intimately connected to the National Park Service. The lodges, hotels, and restaurants within or nearby national parks and monuments were an important part of each visitor’s experience. They became an integral element of the landscape and some, such as the Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone, set national standards and expectations for the kinds of lodging visitors could expect in national parks. Although Faraway Ranch was an example of a vernacular architectural style as opposed to the formal architectural design of the Old Faithful Inn, the rustic, laid-back atmosphere of the ranch echoed that found in concessioner lodgings throughout the West.

Part of a series of articles titled The Story of Faraway Ranch.

Previous: The Guest Ranch Business

Last updated: March 18, 2016