Last updated: July 28, 2023

Article

Chicago's Columbus Park: The Prairie Idealized (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

There are multitudes who rarely get beyond the City limits . . . They need the quietude of the pastoral meadow and the soothing green of grove and woodland in contrast with the noise and glare of the great city.¹

In the early years of the 20th century, when Carl Sandburg wrote the poem, Chicago, he itemized the work being done in the city: shoveling, wrecking, planning, building, breaking, rebuilding. While the poet was eulogizing the work done in the "City of the Big Shoulders . . . proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning," a tall redheaded Danish immigrant with a flowing mustache was endeavoring to create a landscape where the people of the densely populated city could refresh their spirits and refine their sensibilities after laboring so hard.

Jens Jensen came to the United States when he was about 24 years old, settled in Chicago, and promptly fell in love with the Midwest's prairie landscape. Although some thought the prairie was boring, monotonous, and ordinary, Jensen saw great beauty in the midwestern tree-filled groves, long winding rivers, natural rock formations and waterfalls, and the flat stretches filled with colorful native grasses and wildflowers. Rising from street-sweeper and gardener to West Park Commission General Superintendent and Chief Landscape Designer, and then becoming a consulting landscape designer, Jens Jensen began designing Columbus Park in 1915. On a parcel of land that consisted of about 150 acres, named for the explorer who opened the Americas to European settlers, Jensen would attempt to interpret the native landscape of Illinois as comprehensively as possible.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Columbus Park" (with photographs). It was produced in collaboration with the National Park Service Historic Landscape Initiative. Julia Sniderman Bachrach, Preservation Planning Supervisor, Chicago Park District, and Jo Ann Nathan, Director, Jens Jensen Legacy Project, wrote Columbus Park: The Prairie Idealized. Jean West, education consultant, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff edited the lesson plan. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used to teach units on landscape design, urbanization, and conservationism in the early 20th century, or in an interdisciplinary unit on indigenous regional plants and leisure time combining biology and sociology.

Time period: Early 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Chicago's Columbus Park: The Prairie Idealized relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States

(1870-1900)

-

Standard 1B- The student understands the rapid growth of cities and how urban life changed.

-

Standard 1D- The student understands the effects of rapid industrialization on the environment and the emergence of the first conservation movement.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Chicago's Columbus Park: The Prairie Idealized relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

-

Standard C - The student explains and gives examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

-

Standard D - The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

-

Standard D - The student relates such factors as physical endowment and capabilities, learning, motivation, personality, perception, and behavior to individual development.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals' daily lives.Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationships to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants and security.

Objectives for students

1) To examine how the growth of American cities influenced the development and design of public parks such as Columbus Park in Chicago.2) To explain the landscape philosophy of Jens Jensen.

3) To identify methods used to generate public opinion in support of the preservation of historic landscapes such as Columbus Park and other locales.

4) To conduct research about the plants, landscapes, and spaces of their own community and suggest strategies to promote their conservation.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.1) Three maps of the site and surrounding area;

2) Three readings on Columbus Park and Jens Jensen;

3) Seven photos of the site.

Visiting the site

Columbus Park, administered by the Chicago Park District, is located at 500 South Central Avenue in Chicago, Illinois. It is located off I-290, the Eisenhower Expressway, at exit 23. Consult schedules of Chicago Transit Authority buses and the elevated train for public transportation to Columbus Park. The park is open year-round although the field house is closed on Sundays. For information visit the Chicago Park District Web site.Getting Started

Inquiry Question

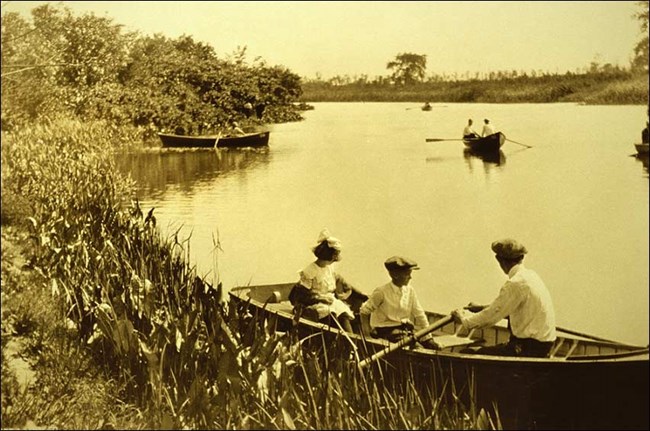

What type of activity appears to be taking place?

What other uses might this space have?

Why might this space be designed in this way?

Setting the Stage

In March of 1930, influential landscape architect Jens Jensen looked back over his accomplishments and talked about his landscape philosophy with a reporter for the Saturday Evening Post magazine.

Not only in the parks, but in private gardens as well, it has become my creed that a garden to be a work of art, must have the soul of the native landscape in it. You cannot put a French garden or an English garden or a German or an Italian garden in America and have it express America . . . Nor can you transpose a Florida or Iowa garden to California and have it feel true, or a New England garden to Illinois, or an Illinois garden to Maine. Each type of landscape must have its own individual expression.1

Jensen pioneered landscape design inspired by the natural landscape. It featured the native plants of a region rather than exotic imports, natural-looking bodies of water, horizontally-layered stonework, winding paths, and sunny meadows.

Jensen did not think that a landscaper merely copied nature; he had to try to idealize nature, distilling its essence, appealing to all five senses. He believed that people, especially city dwellers, ". . . need the out-of-doors, as expressed in beauty and art for a greater vision and a broader interest in life . . . Should this not be told them in the language of their native landscape, so that they may here experience our native beauty, and thus not be deprived of the opportunity to commune with Nature even though it be in very small measure?"2 Within the 150-acre confines of Columbus Park, Jens Jensen recreated the vanishing Illinois prairie for the dwellers of Chicago creating a masterpiece of Prairie landscape design.

1 Jens Jensen as told to Ragna B. Eskil, "Natural Parks and Gardens," Saturday Evening Post, 8 March 1930, 18-19, 169-170.

2 Jens Jensen to the West Park Commission. Forty-Ninth Annual Report of the West Chicago Park Commission, 1917, 18.

Locating the Site

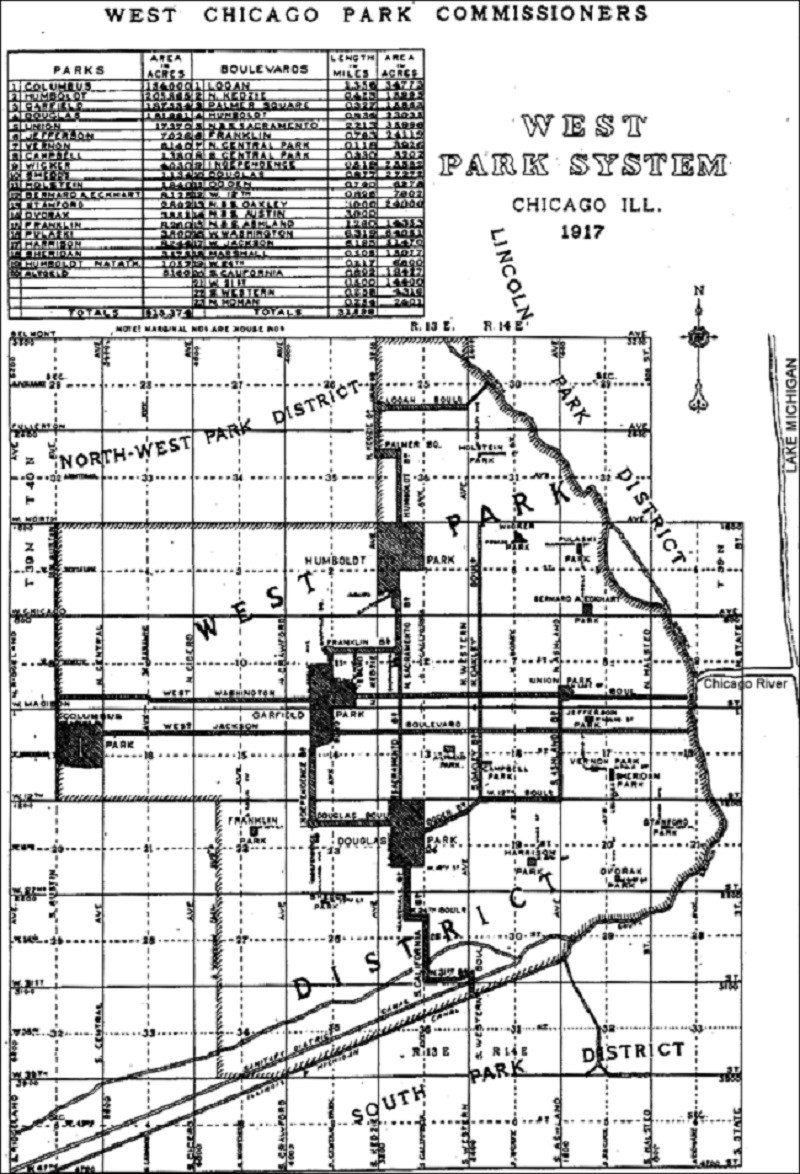

Map 1: Western Park System, Chicago, 1917.

(Courtesy of Chicago Park District Special Collections)

Questions for Map 1

1. On a map of the United States, locate Chicago, Illinois. What do you think the climate is like in Chicago, based on its geographical location? Name one plant you think that you think would do poorly in this climate. Name one plant that you think would do well in this climate.

2. Locate Lake Michigan, the Chicago River, and Columbus Park on Map 1.

3. How many park districts are included on this Western Park System map? How many parks can you identify?

4. What is the pattern of the streets in this area of Chicago? Locate Columbus Park. What is the shape of Columbus Park? Do you think there might be a relationship between the street plan and the park's shape? Explain.

Locating the Site

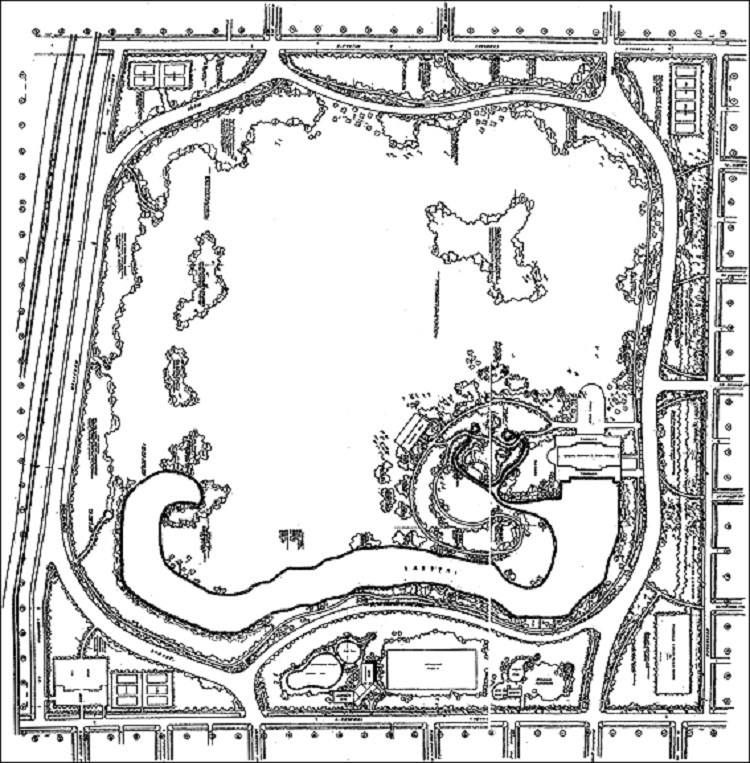

Map 2: Jensen's Original Plan for Columbus Park, 1918.

(Courtesy of Chicago Park District Special Collections)

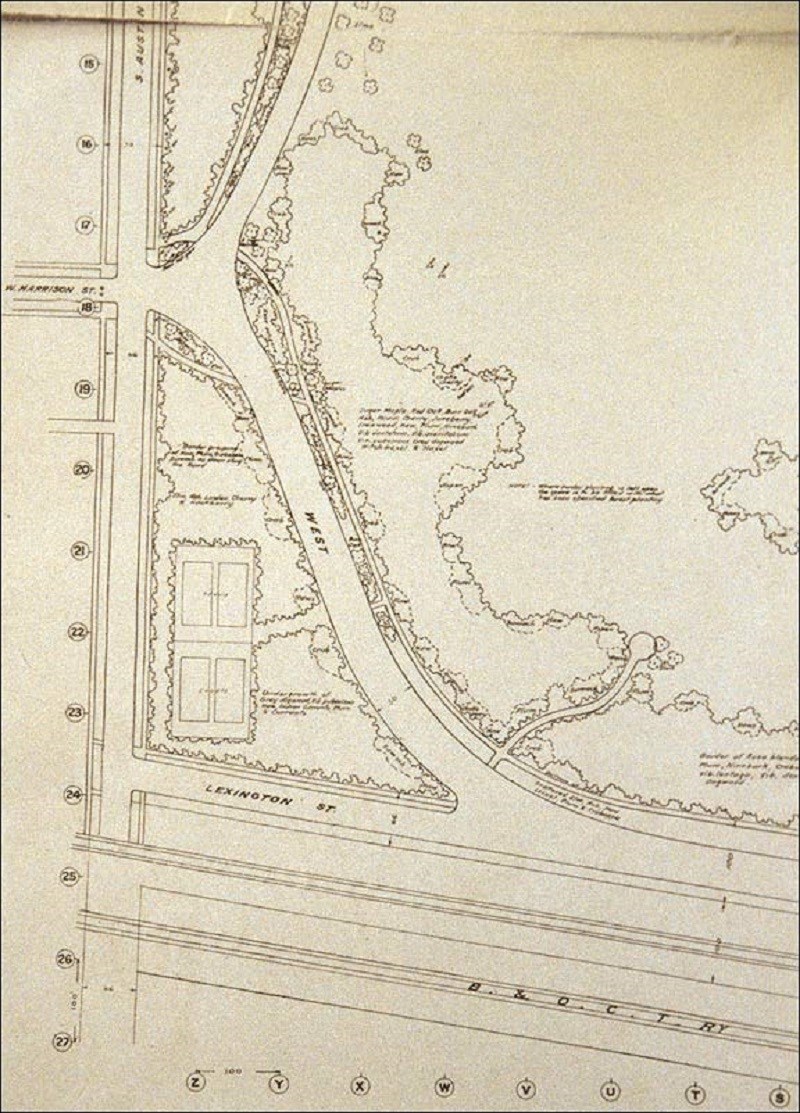

Map 2a: Jensen's Original Plan for Columbus Park, 1918 (Detail).

(Courtesy of Chicago Park District Special Collections)

Questions for Map 2 & 2a

1. What forms the boundary around Columbus Park?

2. Jensen planned to plant trees around the border of the park rather than flowers. Why do you think this was so?

3. Jensen put the recreational features of the park, such as tennis courts, swimming pools, and playgrounds, around its edges, rather than in the middle. Why do you think he did that?

4. Can you determine where the Lagoon (river) is?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: An American Garden

Only 7 miles from Chicago's bustling downtown is Columbus Park, a beautiful landscape of wildflowers, waterfalls, stepping stone paths, and a river. Although visitors might think this is a scenic natural site, it is actually the masterpiece of Jens Jensen (1860-1951), a landscape architect.

Jens Jensen was born in Slesvig, Denmark, but when he wanted to marry Anne Marie Hansen against his family's wishes, the young man decided it would be better if they immigrated to the United States. Following a brief time in Florida and Iowa, the couple moved to Illinois. Jensen fell in love with the flat stretches of prairie filled with colorful grasses and wildflowers. He later recalled:

It was on the train coming into Chicago, and through the car windows I saw silhouetted against the sky the delicate rose of a wild crab apple in early bloom. And when I was told it was a native tree, I said to myself, "That tree is a symbol of the beauty of this prairie landscape we have been passing through." . . . It and the native hawthorn, whose gray horizontal branches are typical of the rolling lands of this mid-country.¹

In 1885, Jensen began working as a street sweeper for Chicago's West Park Commission. In his free time, he began exploring undeveloped areas at the outskirts of the city. Some of these landscapes had forested areas and long winding rivers with natural rock formations and waterfalls. He saw great beauty in the trees and plants that grew naturally in the Midwest at a time when many Americans regarded native plants as weeds.

Nearly every Sunday and holiday, summer and winter, spring and fall, through those early years, I spent botanizing, studying and learning to know every plant that was native to this region. You see, in those days the city limits weren't so far out as they are now, and by riding to the end of the street-car line and then walking, one could see quite a number of plants in a day; and by taking the steam cars, one had a radius of thirty miles or so. I was amazed at the richness of color in every season of the year, particularly in the fall. Northern Europe has some color in the autumn, but nothing to compare with this country.²

Jens Jensen was promoted quickly to the position of gardener. Noticing that many formal gardens with neatly arranged imported plants were languishing, he decided to create a new kind of garden in Union Park. Jensen turned to the plants he had discovered during his weekend "botanizing" to create informal groupings of native wildflowers, an "American Garden."

When, as foreman I had my chance to design a garden, I laid out as formal a plantation as was ever made . . . In these formal beds the foreign plants didn't take kindly to our Chicago soil. They would die out no matter how carefully we tended to them, and our propagating beds were kept busy growing replacements. And after a while I began to think, "There's something wrong here. We are trying to force plants to grow where they don't want to grow."

So I thought I would experiment by moving a number of [native] plants in and seeing how they looked and fared, and in 1888, in a corner of Union Park, I planted what I called the American Garden. As I remember, I had a great collection of perennial wild flowers. We couldn't get the stock from nurserymen, as there had never been any requests for it, and we went out into the woods with a team and wagon and carted it in ourselves . . . People enjoyed seeing the garden. They exclaimed excitedly when they saw flowers they recognized: They welcomed them as they would a friend from home.³

Jensen's wildflower garden was a very new and unusual idea for his time. The American Garden soon became one of the park's most popular attractions.

Even though he was often quite controversial, Jensen's talents were recognized and he became superintendent of 200-acre Humboldt Park in 1895. Because he refused to get involved with political graft, a dishonest park board dismissed Jensen in 1900. However, with the appointment of reform candidates, Jensen returned to the West Park Commission serving as chief landscape architect and general superintendent of the West Park System. Beginning in 1905, he was given the opportunity to redesign existing parks and create some entirely new small parks.

In addition to creating landscapes that would appeal directly to the senses, emotions, and spirits of their visitors, Jensen championed his own philosophy. He was a man of strong opinions, who had arrived at them by both scientific observation and intellectual analysis, and he was willing to speak out. He was physically imposing, standing over six feet tall with keen blue eyes, a full head of red (later, white) hair and a matching flowing mustache. Jensen dressed with flair, often sporting a silk scarf around his neck. He had a dramatic way of speaking to get his point across; some people thought that he sounded like a screeching eagle when he became passionate about a cause. Jensen could also be quite persistent. When a worker installed a waterfall at the Garfield Park Conservatory, Jensen thought it more resembled a mountain cascade than a gentle prairie falls. It was only after Jensen insisted that the workman listen to Mendelssohn's Spring Song that he realized what Jensen envisioned and how he needed to change the waterfall.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why do you think Jensen, who was an immigrant, liked the natural midwestern landscape better than people who were born and raised in the area?

2. Why didn't Jensen believe in creating formal gardens with foreign plantings?

3. Why do you think Jensen called his experimental garden the "American Garden"?

4. How do you think people felt about native wildflowers before Jensen used them in the American Garden? How did they react to them in his garden? Why?

5. Even though Jensen's ideas were controversial, he was very successful. What do you think were some of the reasons for his success?

Reading 1 was compiled from Chicago Historical Society, Prairie in the City: Naturalism in Chicago's Park, 1870-1940 (Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1991); Leonard K. Eaton, Landscape Artist in America, The Life and Work of Jens Jensen (Chicago: The University of Chicago, 1964); Robert E. Grese, Jens Jensen: Maker of Natural Parks and Gardens (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); Jens Jensen, Siftings (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990); and Jens Jensen and Ragna B. Eskil, "Natural Parks and Gardens," Saturday Evening Post, 202, no. 36 (8 March 1930).

1Jens Jensen as told to Ragna B. Eskil, "Natural Parks and Gardens," Saturday Evening Post, 8 March 1930, 18-19, 169-170.

2Ibid.

3Ibid.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Columbus Park--The Prairie Idealized

During the interval between his jobs with the West Chicago Park System, Jensen began a private landscape design business. He mingled with reformers such as Jane Addams, artists including poet Carl Sandburg, and Prairie School architects Frank Lloyd Wright and Dwight Perkins. Jensen created landscapes on private estates from the Midwest to the East Coast for such famous clients as the Ford, Armour, and Florsheim families. Most importantly, his experimentation with natural-looking features matured into a unique landscape design style known as the Prairie style. Drawing on observations and photographs made during his jaunts to the prairie with his family, Jensen incorporated regional trees and flowers in idealized settings of groves, streams, limestone outcroppings, and flat fields of the Midwest. He explained, "As I made my Sunday excursions to the woods for the purpose of studying the native flora, I came to love the native landscape for its contours and physical aspects as well as for its plant life . . . A landscape architect, like a landscape painter can't photograph; he must idealize the thing he sees. In other words, he must try to portray its soul."1

Jensen had big ideas for improving Chicago's west side. He envisioned a 4,000-acre extension to the existing park system with boulevards, community gardens, and playgrounds, but this project was never undertaken. However, between 1916-1920, Jensen's design for a large, completely new park for Chicago was realized. This was Columbus Park.

The Park Commission had acquired a very interesting property on the western edge of Chicago, a 150-acre farm that included fields, wooded areas, and traces of sand dune. Because of the sandy area, Jensen was convinced that the site was an ancient beach formed by glacial action. He explained:

Columbus Park has special interest . . . because it is situated above and below the beach. The natural topography suggested such a layout.This whole park is a typical bit of native landscape idealized as it appears near Chicago. The prairie bluff of stratified rock along the river has been symbolized with plant life. To the west extend the great lawns that symbolize the prairie meadow. These lawn areas are used for golf, but the greens are laid out in such fashion as not to destroy the horizontal aspect of the scene. Limestone rock from our native bluffs, with a backing of native forests has been used in natural walls for the swimming pool and the wading pool for children.2

Incorporating the natural history and topography of the site, Jensen created series of rolling hills, similar to glacial ridges, that encircled the flat, central portion of the park. Within this area, following the traces of the ancient lake beach, Jensen created an artificial prairie river. He included two waterfalls of stratified (layered) rock over which water trickled as if from springs into two brooks meandering and merging into a larger, natural looking lagoon or waterway.

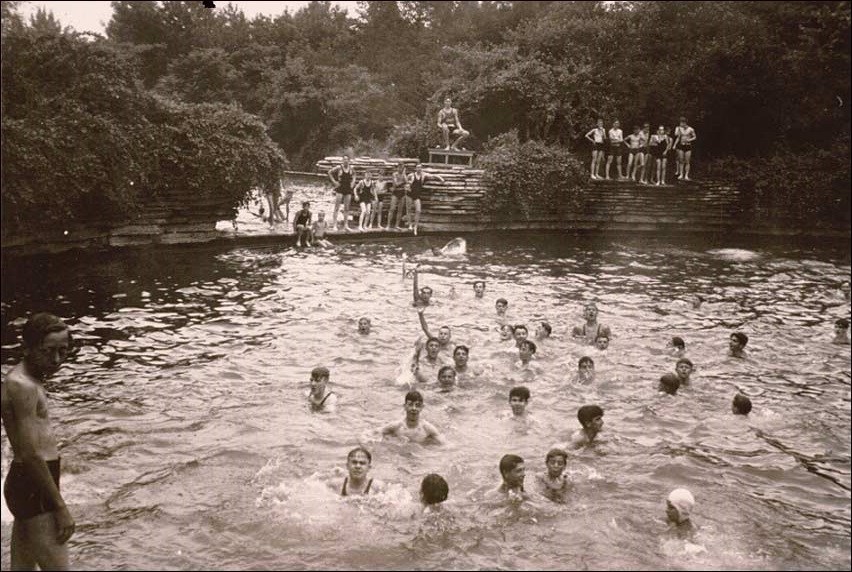

Between the two waterfalls was a sun opening, which was also considered a "clearing." There Jensen placed a "player's green," an area for outdoor theater and music. In another clearing on the perimeter of the park, Jensen designed a children's playground. Instead of filling it with playground equipment, Jensen tried to encourage free play in the open space. He also included a wading pool and a council ring; a circular stone bench for story telling and campfires. He thought it a very American, democratic feature, where everyone could speak on an equal basis. Other features for park programs included a swimming pool with rocky ledges resembling a country swimming hole. It could accommodate 7,000 swimmers.

On the west side of the park, facing the setting sun, Jensen created a flat horizontal meadow. This representation of a natural prairie provided a golf course and ball fields. The area included prairie flowers and shrubs. To simulate forest groves, Jensen used massed elms, ash, maples, hawthorns, and crab apples. Along the brook he planted rushes, cattails, hibiscus, and arrowheads. As he poetically explained in his 1917 report to the Parks Commission:

But in Columbus Park, our meadow with its woodland borders, our river with its dark shaded bluffs, and our groves with their variation of light and shadow, are only a part of the landscape. The sky above, with its fleeting clouds and its star-lit heavens, is an indispensable part of the whole. Looking west from the river bluffs at sundown across a quiet bit of meadow, one sees the prairie reflected in the river below. This gives a feeling of breadth and freedom that only the prairie landscape can give to the human soul.3

Jens Jensen considered Columbus Park his greatest design achievement. With this work he was able to include all of the elements that fully expressed his Prairie style. By using sky, water, land contours, stonework, native plants, clearings, a players green, and a council ring he created a beautiful idealization of the Midwestern landscape. Above all, he created a landscape that was a balm for the human soul, fulfilling his "obligation as a park man to bring this out-of-doors to the city."4

Questions for Reading 2

1. How did Jensen capture the "soul of the landscape" at Columbus Park?

2. What is an example of a design element that was symbolic of the natural landscape and also provided a function for people using the park?

3. Why do you think Jensen considered Columbus Park his greatest design?

4. Do you agree with Jensen that it is necessary to bring the outdoors to people who live in a city? Explain.

Reading 2 was compiled from Malcolm Collier, "Jens Jensen and Columbus Park," Chicago History, no. 4 (Winter, 1975); Robert E. Grese, Jens Jensen: Maker of Natural Parks and Gardens (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); Jens Jensen, Siftings (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990); Jens Jensen to the West Park Commission, Forty-ninth Annual Report of the West Chicago Park Commission, 1917; and Jens Jensen and Ragna B. Eskil, "Natural Parks and Gardens," Saturday Evening Post, 202, no. 36 (8 March 1930).

1 Jens Jensen as told to Ragna B. Eskil, "Natural Parks and Gardens," Saturday Evening Post, 8 March 1930, 18-19, 169-170.

2 Ibid.

3 Jens Jensen to the West Park Commission. Forty-ninth Annual Report of the West Chicago Park Commission, 1917, 18.

4 Jens Jensen as told to Ragna B. Eskil, "Natural Parks and Gardens," Saturday Evening Post, 8 March 1930, 18-19, 169-170.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Beauty of the Wild

In the early 1900s, many natural areas were being destroyed due to the rapid growth of cities and towns. Jens Jensen worried that people were losing touch with nature. He feared that living in an entirely artificial environment would leave humanity spiritually, emotionally, and intellectually empty. Through a variety of ways, Jensen promoted an appreciation for the outdoors to emotionally and spiritually uplift city dwellers. Many of these efforts were geared toward children, such as the addition of children's gardens to several parks. Through these gardens, he believed children would grow up to respect, preserve, and love nature.

Because he appreciated the native environment of the Midwest and was willing to act on his convictions, Jens Jensen emerged as a leader of the conservation movement. During his service on the Chicago City Council's Special Park Commission he identified important natural areas. His efforts ultimately led the city to establish the Forest Preserve of Cook County in 1915. At the time, there were few laws or policies to protect natural scenic areas.

To make Chicagoans aware of the beautiful countryside outside of the city and generate public support for conservation, Jens Jensen and some influential friends sponsored "Saturday Afternoon Walking Trips" beginning in 1908. They took turns leading groups to natural areas outside of the city. Often, more than 200 people participated in these excursions. Because of the popularity of the "Saturday Afternoon" walks, Jensen formed the Prairie Club. Members took walking trips to natural sites threatened by development. Jensen had studied the Indiana dunes and led 300 members to see the site. Five years later, in 1913, the Prairie Club built a beach house on the dunes in Tremont, Indiana and produced and performed a small masque, an outdoor drama, called "The Spirit of the Dunes." The club's efforts accelerated, and a 1917 pageant drew more than 50,000 people to two performances. In 1926, the state responded by creating the Indiana Dunes State Park to protect some 2,250 acres of the dunes.

In 1913, Jensen formed "Friends of Our Native Landscape," an organization devoted to saving natural areas. The first meeting was scheduled to take place in June at a threatened white pine forest near Oregon, Illinois. Jensen thought that outdoor drama would be a compelling way to interest people in conservation. He asked his friend, dramatist Kenneth Sawyer Goodman to write a masque to be performed at the meeting. Goodman wrote Beauty of the Wild, which tells of the plight of nature when the Pioneer and the Builder invaded lands once occupied by Native Americans. Five players and one musician could perform the masque. Each year, the Friends of Our Native Landscape met in a different threatened natural area and members of the organization performed Beauty of the Wild, or other masques that were written in later years. Thousands of people attended these performances.

Jensen was so pleased with the masques that he began including "player's greens," outdoor theater spaces for drama and music, in his designs for private residences and public parks. In his Columbus Park design, Jensen made certain that visitors to dusk performances got to see the sun set over the park's trees and the players illuminated by the rising moon. He envisioned the Columbus Park lagoon as the site of water pageants and designed it with audiences in mind, as well.

In his later years, Jensen retired to his summer property in Ellison Bay, Wisconsin. He helped establish many of Door County, Wisconsin's parks and the Ridges Sanctuary. Above all, he dedicated himself to creating a "school of the soil" where pupils could draw enduring values from rock, sun, water, and wilderness. In 1935, inspired by the folk schools of his native Denmark, Jensen founded "The Clearing," a hands-on school to promote natural landscape design and an ethic of conservation. Jensen directed the school until his death 15 years later, just after his 91st birthday. The Danish immigrant left his adopted nation both a rich legacy of beautiful landscapes and a challenge, to set aside sections of the wilderness so that future generations might study and love it.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Why do you think Jensen took people for walks in the countryside?

2. What is a player's green? Why do you think Jensen included them in his designs? Why do you think Jensen used outdoor theater to try to save natural landscapes?

3. Compare and contrast Jensen's efforts at promoting conservation with modern environmentalists' techniques for involving the public.

4. Why do you think Jensen's organization was called Friends of Our Native Landscape? Why was such a group needed?

5. Considering that Jensen had the opportunity to design landscapes, why do you think he cared about conservation?

Reading 3 was compiled from Robert E. Gres, Jens Jensen: Maker of Natural Parks and Gardens (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); Jens Jensen, Siftings (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990); Jens Jensen and Ragna B. Eskil, "Natural Parks and Gardens," Saturday Evening Post, 202, no. 36 (8 March 1930); and Sid Telfer, Sr., The Jens Jensen I Knew (Ellison Bay, Wis.: Driftwood Farms Press, 1982).

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Recent photo of prairie.

Questions for Photo 1

1. Why do you think some people did not appreciate the natural prairie landscape?

2. Why do you think Jensen liked the natural landscape so much?

Visual Evidence

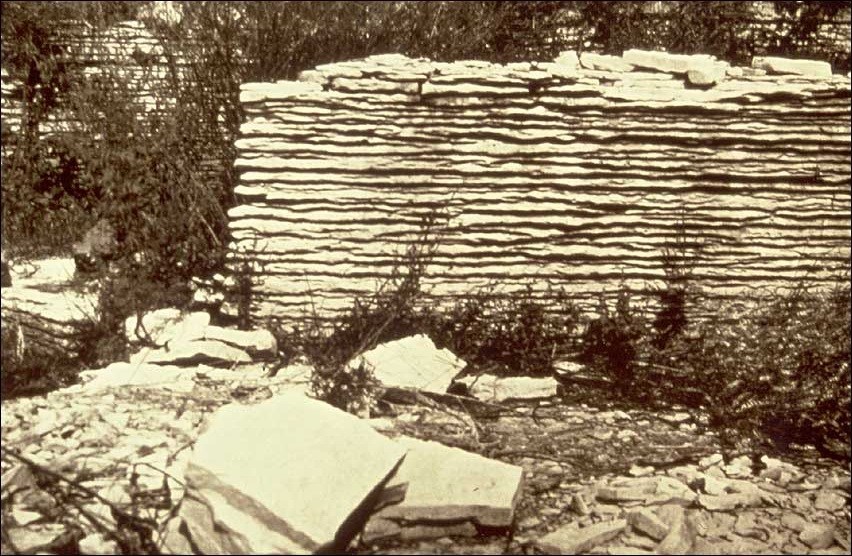

Photo 2: Natural stone outcropping, c. 1910.

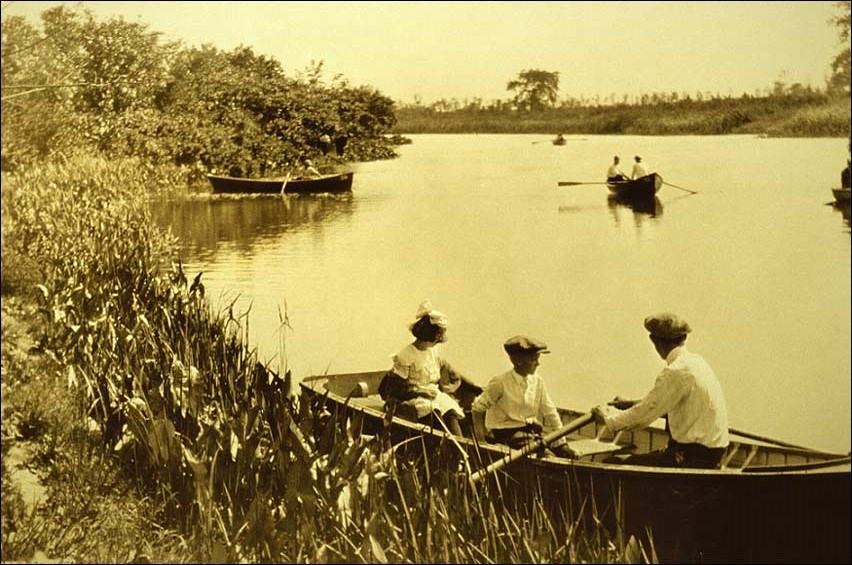

Photo 3: Natural prairie river, c. 1911.

(Courtesy of the Jensen Collection at The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, Illinois)

Jens Jensen took both of these photographs.

Questions Photos 2 & 3

1. Have you ever seen any natural stone formation like this? If so, where?

2. Have you ever seen any natural rivers like this one? If so, where?

3. Why do you think Jensen designed park lagoons to look like this natural prairie river instead of a larger, round, artificial lake?

4. What details do you think Jensen was trying to capture in these photos? How do you think he may have used the photos when designing?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Excavation of the Lagoon, 1916.

(Courtesy of Chicago Park District Special Collections)

Questions for Photos 4 and 5

1. Compare Photos 4 and 5. Does Jensen's artificial lagoon look natural? Explain.

2. Refer back to Map 2 to note the size of the lagoon. What kind of work would have been necessary to create a water feature of this size?

3. What major world event took place around this time? Would that have impacted Jensen's desire to create an "American" park with "democratic" features? Explain.

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: The Council Ring with children, 1920s.

(Courtesy of Frank Waugh Collection, Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, University of Massachusetts, Amherst)

(Courtesy of Chicago Park District Special Collections)

Questions for Photos 6 and 7

1. Why do you think Jensen designed this bench as a large stone circle?

2. Why do you think Jensen designed a city pool as a rural swimming hole? How does having rocky ledges, instead of a flat deck like many modern pools, change the experience for the swimmers at Columbus Park? Why do you think Jensen's pools were eventually replaced with modern pools?

3. To what senses do these features appeal? How did Jensen's design encourage children to exercise mind and body?

4. Jensen originally included no playground equipment in the park. Do you think playground equipment helps or discourages imagination? Explain.

Putting It All Together

The following activities engage students in a number of ways that let them discover how environmentally aware landscaping can play a part in their world.

Activity 1: Save that Site

1. Ask students to research a historic or natural site, either in the community or beyond, which is endangered due to population pressures, pollution, development, etc.

2. Students should share the information they have found about the site, what threatens it, and why it is worthy of being preserved in the form of a skit/play or masque (outdoor play).

Activity 2: Green Scene

1. Based on what Jensen said about creating gardens appropriate to the state or region of the country, ask students to compile a list of native plants which could be used for landscaping in their community. If possible, the list might include photographs and information about whether the plant is annual or perennial, flowering, freeze and drought resistant, and what its mature size might be. Information may be collected with help from the county agricultural extension office, environmental affairs office, the local garden club, a nursery, or other botanical resources.

2. As a class, drawing on the list, design a park or garden for your school or community using native plants and materials.

3. Present the reasons why you think the project should be funded and implemented to the appropriate school, parks, town, or city officials.

Chicago's Columbus Park: The Prairie Idealized--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Columbus Park: The Prairie Idealized, students will learn about a famous landscape artist and his efforts to promote conservation and an appreciation for the native plant life of the United States. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Columbus Park: A Cultural Landscape

A project of the Cultural Landscape Foundation, Columbus Park: A Cultural Landscape is an interactive documentary designed to let you travel on your own through Columbus Park. Use the Visitor Guide to learn about specific topics and use the Archive to search all the material and chart your own course.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation is the only not-for-profit foundation in America dedicated to increasing the public’s awareness of the importance and irreplaceable legacy of cultural landscapes.

Library of Congress

Visit the American Memory Collection Web page to search through the archives for more information about Jens Jensen, Columbus Park, the Chicago Park District, and landscape architecture. Also search for information on the industrialization of America, which spurred the city park movement that swept the nation. Of special note is the Jens Jensen studio and landscape in Illinois featured by the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record.

Columbus Park and Jens Jensen Resources:

Chicago Park District

The Chicago Park District website provides an overview of all the parks and programs of Chicago, including Columbus Park.

Jens Jensen Legacy Project

This website explores Jens Jensen's work as a landscape architect and ecologist and offers a biography and articles about Jens Jensen's life and accomplishments.

Native Plant Conservation Resources:

The California Native Plant Society

This website helps visitors learn what a native plant is, offers a guide to native plants found in the state, and has both educational projects and lesson plans that teachers may use as models.

American Journal of Botany

Browse the American Journal of Botany, a journal devoted to the study of plants, for a variety of articles on botany.

Tags

- illinois

- illinois history

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- chicago

- recreational landscape

- public parks

- urban living

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- art and education

- conservation

- gilded age

- migration and immigration

- immigration and migration

- conservation and outdoor recreation

- progressive era

- early 20th century

- conservation and recreation

- immigrant

- landscape architecture

- twhplp