Last updated: May 9, 2023

Article

Brown v. Board: Five Communities That Changed America (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Probably no case ever to come before the nation’s highest tribunal affected more directly the minds, hearts, and daily lives of so many Americans…. The decision marked the turning point in the nation’s willingness to face the consequences of centuries of racial discrimination.”¹

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court proclaimed that “in the field of public education ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” This historic ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka overturned the Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that had sanctioned racial segregation. The landmark case marked the culmination of a decades-long legal battle waged by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and residents of several communities.

Although people often associate the case with Linda Brown, a young girl whose parents sued so that she could attend an all-white school, Brown v. Board actually consisted of five separate cases.² Originating in four states and the District of Columbia, all began as grassroots efforts to either enroll black students in all-white schools or obtain improved facilities for black students. By the fall of 1952, the Supreme Court had accepted the cases independently on appeal and decided to hear arguments collectively. None of these cases would have been possible without individuals who were courageous enough to take a stand against the inequalities of segregation. Today, several of the schools represented in Brown v. Board of Education stand as poignant reminders of the struggle to abolish segregation in public education.

¹ Richard Kluger, Simple Justice (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), x.

² Brown v. Board consolidated separate cases from four states. A fifth public school segregation case from Washington, DC was considered in the context of Brown, but resulted in a separate opinion. References to Brown in this lesson plan collectively refer to all five cases.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Historic Landmark Nominations, “Robert Russa Moton High School” (with photographs), “Sumner and Monroe Elementary Schools” (with photographs), “Howard High School” (with photographs),and “John Philip Sousa Middle School” (with photographs), as well as the National Register Nomination for “Summerton High School,” and the National Historic Landmark Survey theme study entitled Racial Desegregation in Public Education in the United States. Brown v. Board of Education: Five Communities that Changed America was written by Brenda Olio, former Teaching with Historic Places Historian, and Caridad de la Vega, Historian for the National Park Service National Historic Landmarks Survey. The lesson was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

This lesson plan is made possible by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy (VFH) as part of its African-American Heritage Program, which includes the African-American History in Virginia Grant Program, the African-American Heritage Database Project, and the African-American Heritage Trails Program, a partnership between VFH and the Virginia Tourism Corporation. Through these programs, VFH seeks to increase understanding of African-American history in Virginia; to promote research and documentation of existing African-American historic sites; to strengthen the institutions that interpret African-American history in the state; and to encourage Virginians as well as people from all parts of the nation and the world to visit these sites. For more information, contact VFH, 145 Ednam Drive, Charlottesville, VA 22903-4629 or visit VFH’s website.

*Special note to teacher:

Please explain to students that Brown v. Board consolidated separate cases from four states. A fifth public school segregation case from Washington, DC was considered in the context of Brown, but resulted in a separate opinion. References to Brown in this lesson plan collectively refer to all five cases.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American History courses in units on the civil rights movement, or the history of education in the United States. This lesson could also be used to enhance the study of African-American history in the United States.

Time period: mid-20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Brown v. Board: Five Communities That Changed America relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

-

Standard 4A- The student understands the "Second Reconstruction" and its advancement of civil rights.Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

-

Standard 2D- The student understands contemporary American culture.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Brown v. Board: Five Communities That Changed America relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard A - The student compares similarities and differences in the ways groups, societies, and cultures meet human needs and concerns.

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

-

Standard D - The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.

-

Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard A. The student relates personal changes to social, cultural, and historical contexts.

-

Standard B - The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals daily lives.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

-

Standard G - The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

-

Standard B - The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

-

Standard C - The student describes the various forms institutions take and the interactions of people with institutions.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

-

Standard F - The student describes the role of institutions in furthering both continuity and change.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

-

Standard H - The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice and influence to the examination of persistent issues and social problems.

-

Standard I - The student gives examples and explains how government attempts to achieve their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard A - The student examines issues involving the rights, roles and status of the individual in relation to the general welfare.

-

Standard B - The student describes the purpose of the government and how it's powers are acquired.

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard H - The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice, and influence to the examination of persistent issues and social problems.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard F -The student demonstrate understanding of concerns, standards, issues, and conflicts related to universal human rights.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard A - The student examine the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

-

Standard B - The student identifies and interprets sources and examples of the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

-

Standard C - The student locate, access, analyze, organize, and apply information about selected public issues recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard D - The student practice forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

-

Standard E - The student explain and analyze various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explain the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard G - The student analyze the influence of diverse forms of public opinion on the development of public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard H - The student analyze the effectiveness of selected public policies and citizen behaviors in realizing the stated ideals of a democratic republican form of government.

-

Standard I - The student explain the relationship between policy statements and action plans used to address issues of public concern.

-

Standard J - The student examine strategies designed to strengthen the "common good," which consider a range of options for citizen action.

Objectives

1) To interpret the implication of the Plessy v. Ferguson court case to the history of segregated educational facilities in the United States.

2) To explain the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) role in the desegregation of public education in the United States.

3) To describe the five cases constituting Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case.

4) To evaluate the importance of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case.

5) To determine the implications of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling on public schools in their own community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) one map showing the United States;

2) three readings on the history of school desegregation, the five cases involved in Brown v. Board of Education, and the Supreme Court opinion on Brown v. Board of Education delivered by Chief Justice Warren;

3) six photos of the schools involved in Brown v. Board of Education, and related images.

Visiting the sites

Robert Russa Moton High School [now Robert R. Moton Museum, 900 Griffin Blvd.] (at S. Main St.) is located in Farmville, Virginia. The Robert R. Moton High School is currently undergoing construction for conversion into a museum. The museum is normally open on Wednesday and Friday from 1-3 p.m., and on Saturday from noon to 3 p.m.; however, the site has been temporarily closed since December 2004 due to construction. The center’s mission will be to interpret the history of civil rights in education with particular emphasis on the local story as it relates to the Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education. The museum will feature exhibits, serve as a repository for materials related to the struggle for civil rights in education, and will also serve as an educational center. For additional information please visit the museum’s website or contact them at (434) 315-8775.

Sumner and Monroe Elementary Schools are both located in Topeka, Kansas. Sumner Elementary School (330 Western Avenue) closed its doors as an educational facility in 1996 and is currently vacant. Monroe Elementary School [now Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, 1515 SE Monroe Street] is a unit of the National Park Service commemorating the landmark court case of Brown v. Board of Education. The historic site is open for visitation seven days a week from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., with the exception of Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Day. For more information on the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site please contact the site at (785) 354-4273 or visit the park’s website.

Howard High School [now Howard High School of Technology, 401 East 12th Street] is located in the Eastside neighborhood of Wilmington, Delaware. The school is still in use as an educational facility with the curriculum combining both academics and vocational training. A portion of the building is in use as the Delaware Skills Center. Take I-95 to the Delaware Avenue exit and keep to the right making a right onto Delaware Avenue. Make a left on Walnut Street and follow the road to 13th Street and make a right. Take a right into the Howard High School of Technology parking lot. For more information, please contact the school at (302) 571-5400 or visit the school’s website.

The John Philip Sousa Junior High School [now John Philip Sousa Middle School, 37 Street Ely Place, SE] is located in the southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. The building is still used as a middle school today. For more information please contact the school at (202) 645-3170.

Summerton High School [now Summerton Cultural Arts Center, 12 South Church Street] is located in Clarendon County in Summerton, South Carolina. The building is currently used as the Summerton Cultural Arts Center and houses the school district administrative offices. The space is also used for meetings, conventions, and as an entertainment facility. Plans are being developed for a memorial exhibit commemorating Brown v. Board of Education. For information on site tours please contact Ms. Leola Parks at (803) 485-2325, ext. 230.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

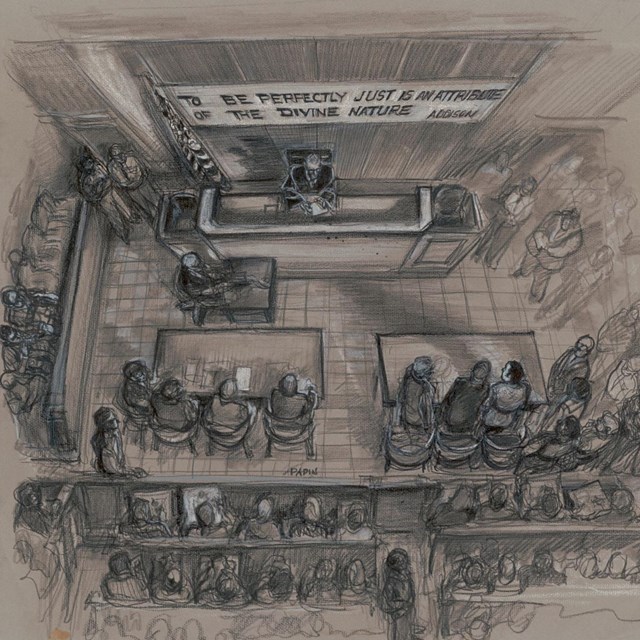

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Setting the Stage

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation which declared “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall be in rebellion of the Unites States, shall be then, thenceforward and forever free.”¹ Although the Emancipation Proclamation declared the slaves free² it was the 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution that legally guaranteed their rights. The 14th Amendment declared the former slaves citizens and proclaimed that states could not “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The 15th Amendment guaranteed the right of all male citizens over the age of 21, regardless of race, the right to vote. An era of substantial freedom and promise for African Americans was ushered in. For the first time the law guaranteed equal access to facilities such as streetcars and public schools. The Freedmen’s Bureau was established by the federal government to assist the former slaves with food and medical attention, and to help establish schools. However, the South attempted to reassert some of the control they lost as a result of the Civil War by segregating (or separating) the races in all aspects of public life. “Jim Crow,” a system defined by the “the practice of legal and extralegal racial discrimination against African Americans,” would curtail many of the freedoms which African Americans³ experienced following the Civil War. During the 1890s the situation for African Americans became increasingly worse throughout the South as race relations deteriorated, violence increased, and the many advances toward integration were virtually eliminated.

It was not until the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that the separate but equal doctrine was officially written into law. The case was based upon the refusal of Homer Adolf Plessy to use the segregated train car assigned to African Americans, and as a result, was imprisoned for the violation of a Louisiana statute. His case thereafter went to the nation’s highest court, the Supreme Court, and the judges considered the issue of “separate but equal” in relation to the 14th Amendment. In the Plessy case, the Supreme Court ruled that separate facilities for blacks and whites were constitutional as long as they were equal. Plessy v. Ferguson stood as the case by which separation of the races was legally sanctioned in the United States and denied African Americans access to many of the white facilities that had been racially integrated after the Civil War.

During the first half of the 20th century educational facilities for African Americans remained in a dire state; although facilities were separate, they were oftentimes not equal. Schools attended by African-American children generally were over-crowded, under-funded, with materials and facilities being old and in disrepair. The injustices suffered by African-American schoolchildren eventually led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to fight against unequal school facilities. Five separate cases contesting inequalities in public education were considered under Oliver Brown et. al. v. the Board of Education of Topeka (Brown v. Board) in 1954.4 Brown v. Board ultimately overturned the decision made in Plessy v. Ferguson.

¹ Quoted in George Brown Tindall and David E. Shi, America: A Narrative History (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996), 720.

² Despite this expansive wording, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Northern control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

³ Quoted in Charles D. Lowery and John F. Marsalek, eds. Encyclopedia of African-American Civil Rights: From Emancipation to the Present (New York: Greenwood Press, 1992), 281.

4 Brown v. Board consolidated separate cases from four states. A fifth public school segregation case from Washington , DC was considered in the context of Brown , but resulted in a separate opinion. References to Brown in this lesson plan collectively refer to all five cases.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Segregation in the United States.

National Park Service.

Key:

1. Topeka, Kansas

2. Summerton, South Carolina

3. Farmville, Virginia

4. District of Columbia (Washington, DC)

5. Wilmington, Delaware

The “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson legally sanctioned the practice of placing children in schools according to race. In the early 1950s, the following 17 states required racial segregation in public schools: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.1 Four others--Arizona, Kansas, New Mexico, and Wyoming--permitted segregation in public schools if local communities wanted it.2

By the fall of 1952, the Supreme Court had agreed to hear arguments in five separate cases that focused on the constitutionality of maintaining segregated public schools. The Court decided to group the cases together under the title Brown v. Board of Education and hear arguments collectively. Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark remarked: “We consolidated them and made Brown the first so that the whole question would not smack of being a purely Southern one.”3

Questions for Map 1

1. Shade in the states where segregation was practiced. What pattern do you notice? Why do you think this was the case?

2. Locate where the five cases represented in Brown v. Board of Education originated. How would you describe the location of each?

3. Why do you think the Supreme Court decided to consider the five cases together?

4. Reread the quote by Justice Clark. Based on Map 1, what do you think he meant?

1 Richard Kluger, Simple Justice (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 327.

2 Jeffrey A. Raffel, Historical Dictionary of School Segregation and Desegregation : The American Experience (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998), 86.

3 Kluger, 540.

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: School Desegregation and the NAACP's Role

As part of the segregation and subordination of African Americans, their schools at the turn of the 20th century were grossly under-funded. This was true even though a third of all school age children in the United States were African American. In the South, African Americans received approximately 12 percent of the funding allocated for public education. It was not uncommon to have a church basement or vacant store serve as a “schoolhouse.” The general attitude toward educating African Americans was in line with a statement made by A. A. Kincannon, Mississippi’s Superintendent of Education in 1899, who stated that “our public school system is designed primarily for the welfare of the white children of the state and incidentally for the negro children.”1 However, African-American churches attempted to bridge the gap in educational facilities for African-American students by founding and funding elementary schools, secondary schools, and colleges.

The 1930s marked the initial thrust at dismantling segregation through the courts. White progressives and black civil rights activists founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the nation’s oldest civil rights organization, in 1909. This organization worked to assure legal rights for African Americans and to improve race relations. The organization’s favored means by which to improve the conditions of a segregated society was through the court system. Therefore, the NAACP established the Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDEF) as a separate entity in 1939 as a non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. Its purpose was to handle the NAACP’s legal activities, particularly cases related to education. The main legal tactic against segregated schools was based upon the fact that equalizing and maintaining two distinct school systems, one for whites and another for blacks, would prove too expensive for local governments to support.

It was not until after World War II when a substantial number of African Americans were exposed to “the democratic and egalitarian rhetoric of the wartime and postwar years,” that many started to push for change in the status quo.2 A sizeable number of African Americans from southern cities moved north during the war in search of well paying defense jobs. For the first time, a solid black working class developed in many major American cities. During the war the NAACP and other groups promoted the “Double V” campaign which sought both victory abroad against fascism and victory at home against racial inequalities. Experiencing more freedoms and equal treatment abroad during the war, black soldiers were motivated to work toward integration at home after their return.

It was not long after the end of the war that African Americans advocating for civil liberties made noteworthy strides toward the equalization of educational facilities. Between 1933 and 1950 the focus of NAACP lawyers was the “desegregation of graduate and professional schools, the equalization of teacher salaries, and the equalization of physical facilities at black and white elementary and high schools.”3 Progress was made in their attacks at the professional and graduate school level with the cases of Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education. The NAACP legally attacked school segregation using the negative sociological implications of segregating the races--a tactic used in 1950 by two cases finally appearing before the Supreme Court. In regard to the Sweatt case, Chief Justice Fred Vinson acknowledged that unequal educational facilities for African Americans violated the mandates set forth in the 14th Amendment. He also agreed that whites received a superior education at the University of Texas Law School by having:

“to a far greater extent [than the state’s new law school for blacks] those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school. Such qualities…include reputation of the faculty, experience of the administration, position and influence of the alumni, standing in the community, traditions and prestige.”4

Chief Justice Vinson furthered this conclusion in the McLaurin case by acknowledging that the separation of George McLaurin within the University of Oklahoma “handicapped” him “in his pursuit of effective graduate study.” He concluded that: “Such restriction impair and inhibit his ability to study, to engage in discussion and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.”5 As a result the Supreme Court ruled in both cases for full and equal admission to the previously all-white institutions. These landmark decisions set the stage for the successful overturn of the Plessy v. Ferguson decision that was the legal benchmark by which African-American students were denied access to an equal college level education.

The NAACP was now confident in their continued fight against unequal educational facilities. At this point Thurgood Marshall, the leading NAACP lawyer, called a conference with other lawyers to decide how to conduct an all-out attack on segregated educational facilities. Marshall proclaimed at the end of the meeting: “We are going to insist on non-segregation in American public education from top to bottom – from law school to kindergarten.”6 As a result of this meeting, the NAACP reaffirmed their resolve in the fight against segregated education. The organization passed a resolution that declared that all new cases addressing unequal education would strive for “education on a non-segregated basis and that no relief other than that will be accepted.”7 The NAACP’s resolution culminated in the five school desegregation cases that were eventually combined into one, Brown v. Board of Education, the case that ultimately overturned Plessy v. Ferguson.

Questions for Reading 1

1. How did the African-American community deal with the inequalities their children had to face to receive an education?

2. How did the NAACP decide to fight against segregation? What other organization was established as a result?

3. What important historical event motivated African Americans to fight for their civil rights? Why? Explain your answer.

4. What was the major focus of the NAACP lawyers between 1933 and 1950? How did they achieve their goals? What did the judges rule? Why?

5. What historic court case did Brown v. Board seek to overturn? What are the details of this earlier case? If needed, refer to Setting the Stage.

Reading 1 was complied from Susan Cianci Salvatore, Waldo Martin, Vicki Ruiz, Patricia Sullivan, and Harvard Sitkoff, Racial Desegregation in Public Education in the United States Theme Study, Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2000; Ralph E. Luker, Historical Dictionary of the Civil Rights Movement (Lanham: MD, The Scarecrow Press, Inc.), 1997. Mark Bauerlein at. alia., Civil Rights Chronicle: The African-American Struggle for Freedom (Lincolnwood, Illinois : Legacy Publishing), 2003. Flavia W. Rutkosky and Robin Bodo, “Howard High School,” (Wilmington, Delaware) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2004 .

1 Quoted in Susan Cianci Salvatore, Waldo Martin, Vicki Ruiz, Patricia Sullivan, and Harvard Sitkoff, Racial Desegregation in Public Education in the United States Theme Study ( Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2000), 28.

2 Ibid., 70.

3 Salvatore et al., Racial Desegregation , 59.

4 Ibid., 69-70.

5 Ibid., 70.

6 Ibid., 70.

7 Ibid.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Challenging School Segregation

The five school desegregation cases that the Supreme Court agreed to hear in the fall of 1952 included: Brown v. Board of Education (Kansas), Briggs v. Elliot (South Carolina), Davis v. Prince Edward County School Board (Virginia), Belton v. Gebhart (Delaware), and Bolling v. Sharpe (District of Columbia). The Court heard the cases under Oliver Brown et al. v. the Board of Education of Topeka and convened to hear arguments on December 9, 1952. Thurgood Marshall and the other National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) attorneys argued that segregated schools violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee to “equal protection of the laws.” Lawyers in the case from the District of Columbia charged that segregation violated students’ Fifth Amendment rights to not “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” The defendants in the cases claimed that operating segregated schools was consistent with custom and law and should be maintained. While the plaintiffs insisted on immediate integration, the defendants held that ensuring that black and white schools were equal was an acceptable compromise.

Brown v. Board of Education

Sumner Elementary School and Monroe Elementary School, Topeka, Kansas

Brown v. Board of Education was initiated by members of the local NAACP chapter in Topeka, Kansas. In the summer of 1950, 13 parents volunteered to try to enroll their children in all-white neighborhood schools for the upcoming school year. Reverend Oliver Brown attempted to enroll his third-grade daughter, Linda, at the all-white Sumner Elementary, which was located only seven blocks from his home. When the request was denied, Linda Brown had to travel further away to attend Monroe Elementary, one of the four schools in Topeka for black students.

On February 28, 1951, the parents filed suit against the Topeka Board of Education. Brown was the first parent listed in the suit and the only male, so the case came to be named after him. The U.S. District Court for Kansas ruled against the parents, but stated in the record that segregated schools did have a negative impact on black children. Brown and the NAACP appealed to the Supreme Court on October 1, 1951.

Briggs v. Elliot

Summerton High School, Summerton, South Carolina

Briggs v. Elliot focused on the inequality of education between two all-white schools and three black schools in Clarendon County School District #22. The all-white Summerton High School was described as “modern, safe, sanitary, well equipped, lighted and healthy.” The black schools were seen as “inadequate…unhealthy…old and overcrowded and in a dilapidated condition.”1

In November 1949, more than 100 people petitioned the school district to address the differences in budgets, buildings, and services available for black and white students. When the petition was ignored, the local branch of the NAACP filed Briggs v. Elliot in Federal District Court. The plaintiff whose name led the list was Harry Briggs, a service station attendant with school-age children. R. W. Elliot was the chairman of the board for the school district.

In May 1951, the court ruled against the petitioners, but told the defendants to establish equal facilities for black students. The NAACP lawyers appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court, however, returned the case to the district court for a second hearing. After learning that Clarendon County was committed to building more schools for African Americans and improving teacher salaries, equipment, etc., the district court upheld its decision. In May 1952, the NAACP lawyers appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court again, this time claiming that segregation itself violated the 14th Amendment guarantee to “equal protection under the laws.”

Belton v. Gebhart, Bulah v. Gebhart

Howard High School, Wilmington, Delaware

Philanthropist Pierre S. DuPont improved educational opportunities for black students in Delaware by funding the construction of dozens of schools. Howard High School, located in Wilmington, was among them. Designed by a nationally known expert in school design, Howard High opened in 1929 as the only school in Delaware offering a complete high school education to black students.

Black students living in Claymont, Delaware, spent up to an hour each way traveling the nine miles to Howard High, while the all-white Claymont High was located right in their neighborhood. Aside from the distance, Claymont School was better equipped and less crowded. With an enrollment of several hundred students, Claymont was situated on a 13-acre campus with playing fields and a running track. Howard High School, on the other hand, had 1,274 students and was in a “congested industrial area, with no play space.”2

After seeking legal advice from NAACP lawyers in March 1951, a group of parents asked the school board to admit their children to Claymont High. When the State Board of Education refused, the parents sued the state of Delaware. The court case was filed in August 1951 as Belton v. Gebhart (a member of the State Board of Education). A second case, Bulah v. Gebhart, was brought by Sarah Bulah, a parent who had made several attempts to convince the Delaware Department of Public Instruction to provide bus transportation for black children in the town of Hockessin. Particularly galling was the fact that a bus for white children passed her house twice a day, but would not pick up her daughter. The Delaware court concluded that “the mental health problems created by racial segregation attributed to a lack of educational progress, and furthermore that under the separate but equal doctrine the plaintiffs had a right to send their children to the white schools.” This was the first time in the United States that a white high school and elementary school were ordered to admit black children.3 The State Attorney General immediately filed an appeal. On August 28, 1952, the Supreme Court of Delaware upheld the decision. In late November, the State Attorney General filed a petition for the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case.

Davis v. Prince Edward County School Board

Robert Russa Moton High School, Farmville, Virginia

Prior to 1939, the only secondary school education available to African Americans in Prince Edward County, Virginia, was a few extra grades in one elementary school.4 That year, however, a new black high school named after the president of Tuskeegee Institute opened. As with the other 11 high schools for African Americans in Virginia, Robert Russa Moton High School proved to have inadequate facilities. The one-story brick structure had no gymnasium, cafeteria, lockers, or auditorium with fixed seating (unlike Farmville High School for whites only). Built to accommodate 180 students, the school was overflowing with more than 400 students by 1950. Eventually, three temporary buildings (dubbed the “tar paper shacks” because of the flimsy material covering the wooden framework) were constructed to ease overcrowding.

On April 23, 1951, students of Moton High School led a strike to protest the overcrowded conditions, the inadequate shacks, and the school boards unwillingness to build a new high school. After consulting with the Richmond, Virginia office of the NAACP, they decided to sue for integration (not for just improved facilities) and to continue the strike until the school year ended on May 7. On May 23, attorneys filed suit in the Federal District Court for the immediate integration of Prince Edward County schools. The court’s decision in the case known as Davis v. the County School Board of Prince Edward County favored the county. The case reached the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal.

Bolling v. Sharpe

John Philip Sousa Junior High School, Washington, D.C.

In the first half of the 20th century, racially segregated schools were the norm in the nation’s capital just as in other schools of the South. Unlike other school systems, however, Washington, D.C. schools depended largely on congressional funding. As the black population in the District expanded greatly between 1930 and 1950, overcrowding in black schools became typical.

By the fall of 1950, some frustrated parents had formed the Consolidated Parents’ Group and were ready to legally challenge segregated schools in the District. With the help of attorney James Nabrit, professor of law at the all-black Howard University, the group decided to take a stand at the new all-white John Philip Sousa Junior High School. In a carefully planned effort, 12-year old Spottswood Bolling and 10 other black students tried to gain admission to John Philip Sousa Junior High School on September 11. The principal refused to admit the children, so they were forced to attend the all-black Shaw Junior High. Sousa Junior High was described as a “spacious glass-and-brick structure located across the street from a golf course in a solidly residential section of Southeast Washington.”5 It had 42 classrooms, a 600-seat auditorium, a double gymnasium, and a playground with several athletic courts. Shaw, on the other hand, was “forty-eight years old, dingy, ill-equipped, and located across the street from The Lucky Pawnbroker’s Exchange.”6 It had a makeshift gymnasium, and its playground was too small for a ball field.

Nabrit filed suit on behalf of Bolling and four other plaintiffs against C. Melvin Sharpe, president of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia. Nabrit did not present evidence that the schools were inferior to the facilities for white students. Instead, the Bolling v. Sharpe case charged that segregation in itself was discrimination and violated students’ rights to due process under the Fifth Amendment. This tactic differed from the other cases because the 14th Amendment applied to states and therefore was not applicable in the District of Columbia. The District Court Judge dismissed the case. Nabrit filed an appeal and was awaiting a hearing when the Supreme Court sent word that it was interested in considering the case along with the other four segregation cases already pending.

The arguments for all five cases were completed by December 11, after only three days before the Court. The Supreme Court justices were divided on the proper decision and deliberated for nearly six months.7 In June 1953, instead of issuing a ruling, the Court told both sides to come back in the fall to argue whether the 14th Amendment was originally intended to apply to segregation in public schools. The Court reconvened on December 7 and finally issued its historic decision on May 17, 1954. More than half a century after Plessy v. Ferguson established the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Supreme Court unanimously declared that segregation in public schools violated the 14th Amendment and was unconstitutional. In a separate opinion for Bolling v. Sharpe, the Court stated: “In view of our decision that the Constitution prohibits the states from maintaining racially segregated public schools, it would be unthinkable that the same Constitution would impose a lesser duty on the Federal Government.”8

Questions for Reading 2

1. Which constitutional amendments did the NAACP claim that segregated schools violate? What basic rights do each of these amendments protect?

2. Briefly explain each case. How did each one reach the Supreme Court?

3. When did the Supreme Court first convene to hear arguments? When was a ruling finally issued? Why do you think it took the Court so long to decide?

4. In your own words, explain the Court's rulings. Why was a separate opinion rendered for the Bolling v. Sharpe case?

5. Several of the schools involved in the five cases (and highlighted in the reading) still stand today and have been designated National Register of Historic Places properties or National Historic Landmarks. Do you think it is important to research, document, and recognize properties associated with the Brown v. Board of Education decision? Explain your answer.

Reading 2 was compiled from Richard Kluger, Simple Justice (New York: Vintage Books, 1977); Martha Hagedorn-Krass, “Sumner Elementary School and Monroe Elementary School” (Shawnee County, Kansas) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1991; J. Tracy Power, “Summerton High School” (Clarendon County, South Carolina) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1994; Flavia W. Rutkosky, “Howard High School” (New Castle County, Delaware) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2004; Jarl K. Jackson and Julie L. Vosmik, “Robert Russa Moton High School” (Prince Edward County, Virginia) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1994; Susan Cianci Salvatore, “John Philip Sousa Junior High School” (Washington, D.C.) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2001; and Susan Cianci Salvatore, Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Vicki L. Ruiz, Patricia Sullivan, Harvard Sitkoff, “Racial Desegregation in Public Education in the United States,” National Historic Landmarks Theme Study, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2000.

1 J. Tracy Power, “Summerton High School ” (Clarendon County , South Carolina) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1994), 7.

2 Flavia W. Rutkosky and Robin Bodo, “Howard High School” (New Castle County, Delaware) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2004), 14.

3 Ibid., 16.

4 Jarl K. Jackson and Julie L. Vosmik, “Robert Russa Moton High School” (Prince Edward County, Virginia) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1994), 9.

5 Richard Kluger, Simple Justice (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 521 quoted by Susan Cianci Salvatore, “John Philip Sousa Junior High School” (Washington , D.C.) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form (Washington , D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2001), 11.

6 Ibid., 12.

7 Power, “Summerton High School,” 9.

8 Quoted in Salvatore, 14.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Supreme Court's Opinion in Brown v. Board of Education

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion.

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called "separate but equal" doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537. Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case, the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools.

The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not "equal" and cannot be made "equal," and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. Because of the obvious importance of the question presented, the Court took jurisdiction. Argument was heard in the 1952 Term, and reargument was heard this Term on certain questions propounded by the Court.

Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive….

…there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other "tangible" factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.

….In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Because these are class actions, because of the wide applicability of this decision, and because of the great variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases presents problems of considerable complexity. On reargument, the consideration of appropriate relief was necessarily subordinated to the primary question -- the constitutionality of segregation in public education. We have now announced that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. In order that we may have the full assistance of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will be restored to the docket, and the parties are requested to present further argument on Questions 4 and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargument this Term….

It is so ordered.

Questions for Reading 3

1. According to Chief Justice Earl Warren, how did the Delaware case differ from the rest? Based on what you learned in Reading 2, why did the case reach the Supreme Court?

2. What was the result of the “reargument” heard by the Court?

3. What do you think Chief Justice Warren meant when he wrote, “Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases?”

4. How would you summarize the Court's opinion?

5. The Court's opinion in Brown v. Board declared that racial segregation was unconstitutional, but it did not decree how desegregation would take place. Based on the opinion's final paragraph, why was this the case? How did the Court plan to address the issue?

6. One year after the first Brown decision the court issued the ruling known as Brown II which ordered schools to integrate “with all deliberate speed.” Why do you think that a second ruling was needed to force the issue?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Robert Russa Moton High School Farmville Virginia.

(Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Photo 2: Classroom in temporary building, Robert Russa Moton High School.

(Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Photo 1 shows two of the temporary buildings erected on the grounds of R.R. Moton High School in the early 1950s. The permanent building is seen in the middle of the photograph.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Why were the temporary buildings constructed? (Refer back to Reading 2 if necessary.)

2. How would you describe the interior and exterior of the temporary buildings? What did students at the school term the structures?

3. How did these structures contribute to the students' decision to strike in 1951?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Auditorium at Farmville High School, Farmville, Virginia.

( Record Group 2, Records of the District Courts of the United States, 1865 - 1991

National Archives and Records Administration, Mid Atlantic Region)

Photo 4: Auditorium at Robert Russa Moton High School, Farmville , Virginia.

(Record Group 2, Records of the District Courts of the United States, 1865 - 1991

National Archives and Records Administration, Mid Atlantic Region)

Both of these photos were included as exhibits by the plaintiffs in the court case Dorothy E. Davis, et al. versus County School Board of Prince Edward.

Questions for Photographs 3 and 4

1. Based on Reading 2, what were the basic details of the case in Farmville?

2. How would you describe each auditorium?

3. Why do you think the plaintiffs presented these photos as exhibits in the court case? Do you think they would have been effective? Why or why not?

(Courtesy of the St. Louis Post Dispatch)

Questions for Photo 5

1. What organization do you think sponsored this protest against segregated schools? In what other ways did this organization further the fight against segregated schools? (Refer back to Reading 1 if necessary.)

2. How do you think the protestors felt?

3. What do you think is the usefulness of having such a young child protest school segregation? What is the message that the organization is trying to convey? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Mrs. Nettie Hunt and daughter on the steps of the Supreme Court, Washington, D.C., Nov., 1954.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The Supreme Court's decision on the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954 marked a culmination in the NAACP's plan to end segregation in schools. African-American parents throughout the country like Mrs. Hunt, shown here, explained to their children why this was an important moment in history.

Questions for Photo 6

1. What is Mrs. Hunt holding?

2. What building are Mrs. Hunt and her daughter sitting in front of? How does this add to the impact of the photo?

3. The child in the photo was only three years old at the time. How might Mrs. Hunt have felt when she explained the court ruling to her daughter?

Putting It All Together

In this lesson, students learn about the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The following activities will help them apply what they have learned.

Activity 1: Massive Resistance

Explain to students that Prince Edward County, Virginia, garnered national attention in the years following the Brown ruling as the most extreme example of “massive resistance” to integration. Ask students to research what happened in Prince Edward County from the time of the Brown decision until 1964 when Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County was argued before the Supreme Court. Students should prepare a written report detailing how “massive resistance” impacted integration in Virginia.

Activity 2: The NAACP

Have students conduct research on the NAACP, the nation's oldest civil rights organization. Questions to consider include:

-

Why, when, and how was the NAACP founded?

-

What role did the NAACP play in ending segregation?

-

What were some of the NAACP's major civil rights accomplishments during the 1960s?

-

What methods did they use to gain “victories” in the fight for civil rights?

Students may summarize their findings in a written report or create a timeline illustrating the NAACP's history.

Activity 3: School Segregation in the Local Community

Divide students into two groups and ask one group to conduct research on public schools in their town or county in the period leading up to the Brown ruling and the other to research schools in the several years following the Brown ruling.

Questions for the first group to address include: Were schools segregated? How many schools (elementary and secondary) were there for blacks and whites? Were any of the schools involved in local law suits over segregation? Do any of the schools from the period remain today? Questions for the second group include: What was the School Board's reaction to the ruling? What specific changes occurred as a result of Brown v. Board of Education? When did these changes take place? Did it take additional court rulings before the school system integrated for good?

After the research is complete, have each group explain its findings. If possible, have students create an exhibit to display at school, the local library, or historical society. The exhibit should include historical and/or modern photographs of school buildings as well as images of students or newspaper headlines from the period. Complete the activity by discussing with students how local events can have national significance and, in turn, how national events can impact the local community.

Brown v. Board: Five Communities That Changed America--

Supplementary Resources

By studying Brown v. Board: Five Communities That Changed America students learn about the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

University of Michigan Library

Visit the University of Michigan Library website for a list of cases associated with Brown v. Board. Also included is the full text of Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County.

University of Virginia: Civil Rights in U.S. and Virginia History

This website stems from a course at the University of Virginia that covers segregation and the Civil Rights Movement in a local and national context. The website offers a wealth of documents, images, and sources, including images from the Davis case.

National Park Service

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The site is located at Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. Monroe was the segregated school attended by the lead plaintiff's daughter, Linda Brown, when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in 1951. The park's web page provides in-depth information on the case as well as related cases, and visitation and research information.

The National Register of Historic Places online itinerary Places Reflecting America’s Diverse Cultures highlights the historic places and stories of America’s diverse cultural heritage. This itinerary seeks to share the contributions various peoples have made in creating American culture and history.

Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute

The Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute is an educational partnership between Yale University and the New Haven Public Schools designed to strengthen teaching and learning in schools. The website features curricular resources produced by teachers participating in Institute seminars, including "From Plessy v. Ferguson to Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court Rules on School Desegregation."

“With an Even Hand”: Brown v. Board at 50

This Library of Congress online exhibition examines the court cases that laid the ground work for the Brown v. Board decision, explores the Supreme Court argument and the public's response to it, and provides an overview of the decision's aftermath.

Brown at 50: Fulfilling the Promise

This website, sponsored by Howard University School of Law, commemorates the 50th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The site features a chronology of events leading up to the case and beyond, biographical sketches of some of the figures involved in the case, as well as the full text of the Supreme Court's decision.

Robert Russa Moton Museum

The Robert Russa Moton Museum is committed to the preservation and positive interpretation of the history of civil rights in education, specifically as it relates to Prince Edward County and the role its citizens played in America's struggle to move from a segregated to an integrated society. The website includes a timeline of the school's history and links to other sites dealing with the Civil Rights Movement.

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People is the nation's oldest civil rights organization. The NAACP website offers a detailed timeline of the organization's trials and triumphs.

The Supreme Court Historical Society

The Supreme Court Historical Society, a private non-profit organization, is dedicated to the collection and preservation of the history of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Society accomplishes its mission by conducting educational programs, supporting historical research, publishing books, journals, and electronic materials, and by collecting antiques and artifacts related to the Court's history. The society's website offers extensive information on the history of the Supreme Court and its justices as well as details of how the Court functions.

Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education

This online exhibit, produced by the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, includes sections on the history of segregation in America, the fight to end segregation, and the legacy of the Brown ruling.

NPR: Brown v. Board of Education

The National Public Radio's website features a special section on Brown v. Board of Education. Students can listen to radio interviews with people involved in the case, including a man who attended a segregated school in Topeka, Kansas, in the 1950s, as well as one of the individuals who helped lead the student strike in Farmville, Virginia.

American Radio Works – Remembering Jim Crow

Remembering Jim Crow is an online documentary glimpse at the system of Jim Crow explored through text, pictures, audio clips and slide shows. Sponsored by American Radio Works, the web site features personal accounts offering different perspectives on how the system of Jim Crow affected individuals throughout the country. The site also offers a sampling of Jim Crow laws, with a particular section addressing those specifically related to education.

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

The Judicial System

The Judicial SystemHow does the judicial system work? What is a federal court? Why are people trying to reclassify certain offenses?

-

Federalism

FederalismWhat is federalism? How have some Americans used debates about federalism to promote segregation?

-

Teaching Engaged Citizenship

Teaching Engaged CitizenshipUse these mini-lessons to fit civics education into a variety of social studies classrooms.

Tags

- desegregation

- desegregation of public education

- brown v. board of education

- brown v. board of education national historic site

- naacp

- u.s. supreme court

- kansas

- kansas history

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- african american history

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- civil rights

- south carolina

- south carolina history

- delaware

- delaware history

- virginia

- virginia history

- washington d.c.

- dc history

- civics

- late 20th century

- shaping the political landscape

- art and education

- education

- segregation

- u.s. supreme court decisions on school desegregation

- education history

- mid 20th century

- twhplp

- wwii aah