Last updated: April 8, 2024

Article

A Nation Repays Its Debt: The National Soldiers' Home and Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio (Teaching with Historic Places)

Photo by Ted, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21636526

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

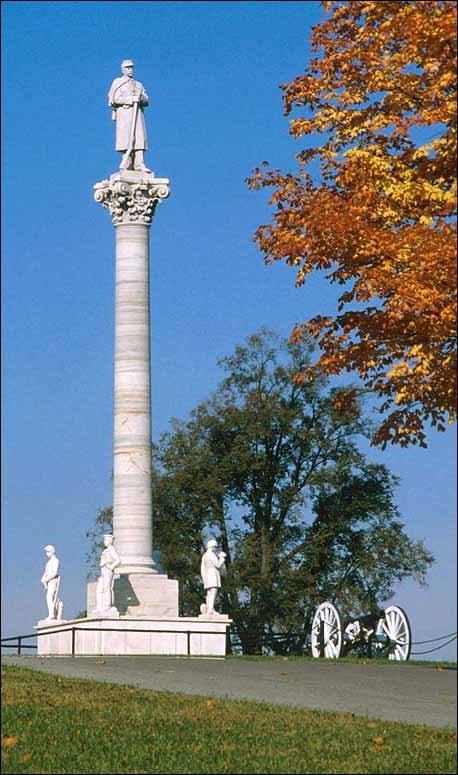

More than 3000 of the disabled veterans who were residents of the Central Home since its establishment have died and been buried with military honors in the grove west of the Hospital, which had been tastefully laid out for a cemetery. "Their comrades, officers and men have erected there a beautiful monument of Peru white marble, fifty feet high, and surmounted with a splendid figure of a private soldier. It was unveiled on the 12th of September, 1887, [The year in this quote is incorrect. The monument was actually dedicated in 1877.] by the President of the United States, with grand ceremonies and in the presence of 25,000 people. On the pedestal are the words 'To our fallen Comrades' and 'These were honorable men in their generation.'…"¹

Upon entering Dayton National Cemetery, the hilly landscape is dotted with uniform marble headstones, all in neat rows with the Dayton Soldiers Memorial standing tall and proud in the center. The more than 100 acres of cemetery landscape is bathed with sunshine today, as there are few trees to shade visitors and mourners. Except for the sounds of birds, there is a solemn quiet. Beyond the gentle hills and headstones and over the horizon, you might glimpse a large old brick soldiers' home building which was built to house disabled Union veterans from the Civil War. One visitor noted the inhabitants and the atmosphere of the home when visiting in 1878:

THE HOSPITAL Was visited in the afternoon at 3 o'clock. The men who were able to walk gathered in the beautiful and spacious reading-room, adorned with flower-plants, and decorated with pictures. Service was held here to the profound satisfaction of the sick and wounded, and it was a delightful little meeting, one that I shall ever remember.

THE OFFICERS Of the Home are sick or disabled soldiers of the late war. They have all seen hard service…²

The cemetery and soldiers' home are part of the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Today's visitors to the facility that once housed the soldiers' home will notice the same attention to care and comfort of veterans. One can pass through the same ornate Anderson Gate onto 348 acres of well-maintained grounds that preserve the same layout as the original campus. The historic campus and cemetery today tells the story of how our nation recognizes the sacrifice of veterans - in life and death.

² George Washington Williams, "The Soldiers' Home: Its Officers and Men," The Cincinnati Commercial, 24 November 1878.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places nomination for the Central Branch, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Dayton, Ohio and other sources. The lesson was written by Paul LaRue, history teacher at Washington Senior High School in Washington Court House, Ohio with help from his 2003-2004 history class students. The lesson was edited by the History Program staff of the National Cemetery Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson covers aspects of late 19th-century U.S. history, social studies, Civil War, Reconstruction, and geography. Students will gain an understanding and appreciation for the challenges involved in carrying out a program to care for the needs of Civil War veterans and to mark their graves after their deaths.

Time period: Civil War Era to 1929

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

A Nation Repays Its Debt: The National Soldiers' Home and Cemetery in Dayton, OH relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850 to 1877)

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the social experience of the war on the battlefield and home front.

-

Standard 3A- The student understands the political controversy over Reconstruction.

-

Standard 3C- The student understands the successes and failures of Reconstruction in the South, North, and West.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

A Nation Repays Its Debt: The National Soldiers' Home and Cemetery in Dayton

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard A - The student compares similarities and differences in the ways groups, societies, and cultures meet human needs and concerns.

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

-

Standard C - The student explains and give examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

-

Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard A. The student relates personal changes to social, cultural, and historical contexts.

-

Standard B - The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals daily lives.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

-

Standard G - The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

-

Standard B - The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard B - The student identifies and interprets sources and examples of the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

Objectives for students

1) To outline the steps the U.S. government took to care for and honor its veterans after the Civil War.

2) To explain how the success of the Dayton soldiers' home launched a nationwide system.

3) To list at least three factors officials used in creating standards for burial markers and compare and contrast the options considered to meet those standards.

4) To locate a veteran's grave in their community and research and write a biography on the life of that veteran.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

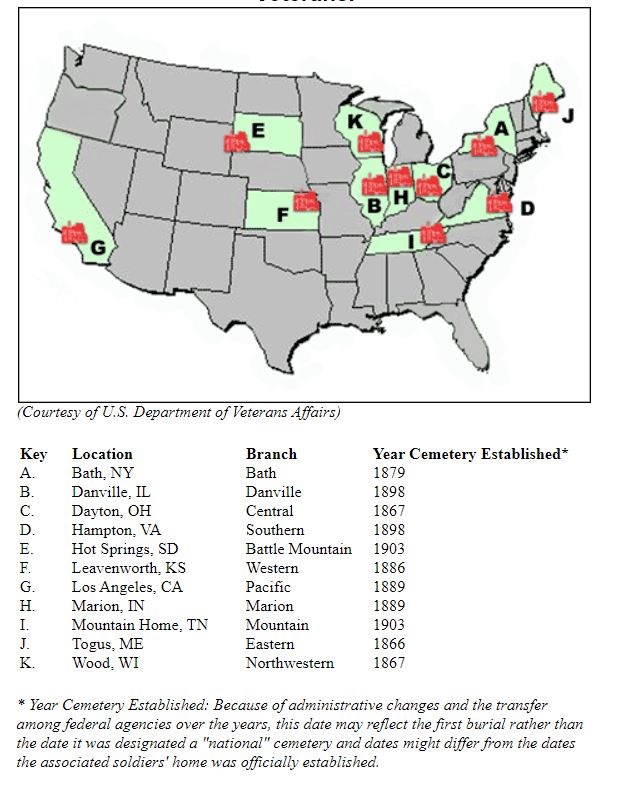

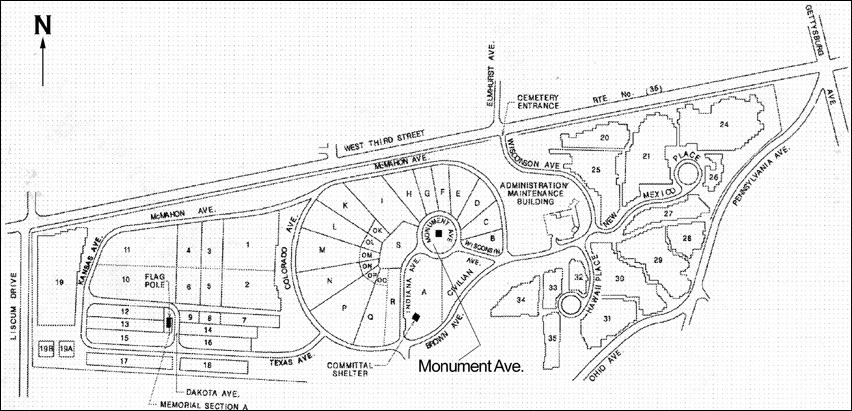

1) two maps of the location of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in the United States and the cemetery layout;

2) four readings about the history of the soldiers' home and national cemetery, burial practices, and a poem honoring those who die during war;

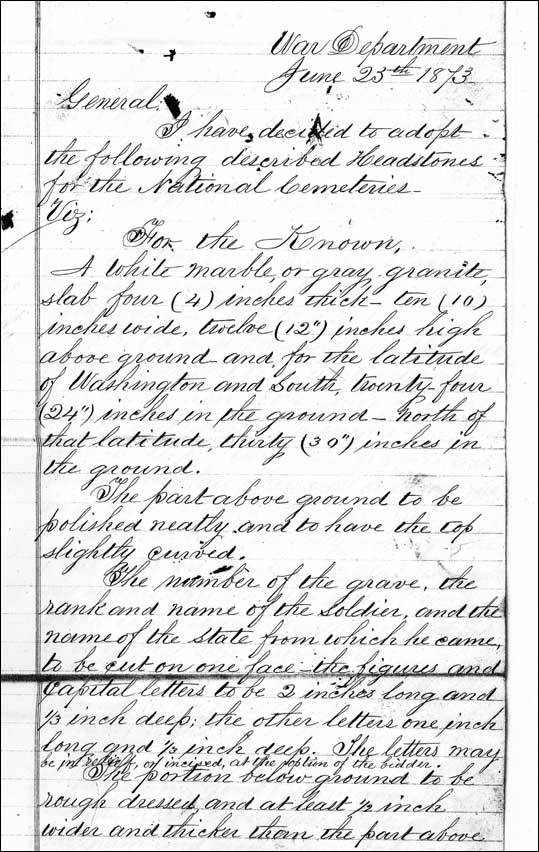

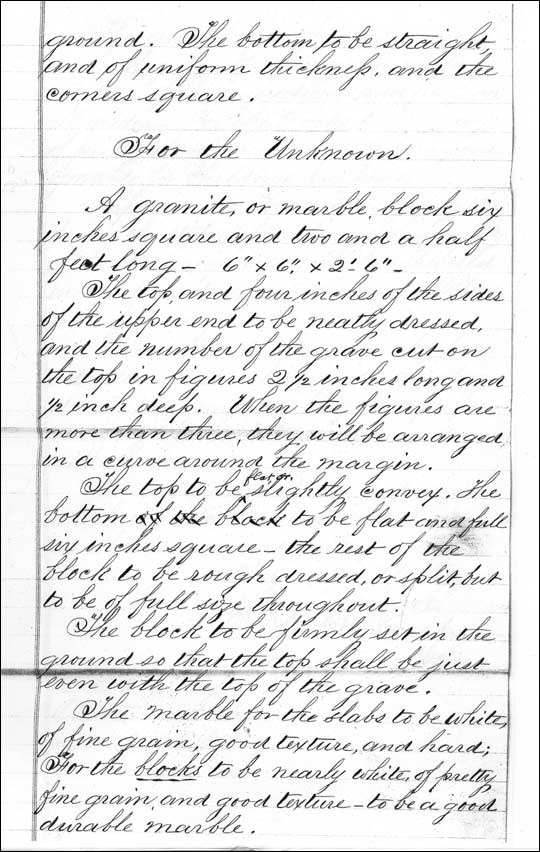

3) one illustration of a letter regarding the selection of headstones;

4) five photos of the cemetery, monument, and grave markers.

Visiting the site

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, including Dayton National Cemetery, is now the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and National Cemetery. The historic district includes 261 acres of the original Soldiers' Home and Cemetery, including 44 contributing buildings. The district is located at 4100 West Third Street in Dayton, Ohio. Dayton National Cemetery is open daily from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. It is one of 120 national cemeteries and 33 soldiers' lots managed by National Cemetery Administration (NCA). For more information, contact the Dayton National Cemetery at (937) 262-2115 or visit the NCA website. For information about visiting the VA Medical Center, please call (937) 268-6511, or visit the Department of Veteran Affairs website.

Inquiry Question

Describe what you see in the photo. What might be the reason for this particular layout?

Setting the Stage

More than 3.2 million soldiers are estimated to have served in the Civil War: 2.2 million Union soldiers and approximately 1 million Confederates. Of these, the death toll reached approximately 364,000 Union soldiers and 133,821 Confederate soldiers.¹ When the war ended, the graves of the nearly a half million Union and Confederate soldiers who died in action, or of wounds and disease lacked official recognition. Meanwhile, approximately 2.7 million veterans began to return home.

The U.S. Government had never before faced such a situation. What level of care and attention should be provided to the returning Union veterans or their survivors? The federal government responded quickly through the creation of a network of regionally dispersed "Soldiers' Homes" and national cemeteries or soldiers' lots.

Between the war's end and 1870, U.S. Army troops scoured battlefields and other areas of fighting in search of the graves of only Union dead, which were typically shallow and unmarked. The graves were located and used to determine appropriate locations for national cemeteries. The earliest national cemeteries were small, at less than 10 acres, and were located near significant battlegrounds, hospitals, Prisoner of War (POW) camps, or convenient railroad connections. In 1862, 14 national cemeteries were created; 10 years later, another 62 were established. The soldiers' homes also had affiliated cemeteries to serve veterans who died in residence or were delivered to the facility. These would eventually become national cemeteries, and graves were initially marked with temporary wooden headboards painted white.

The task of providing Union graves with a permanent headstone took longer than was expected, stretching into the mid-1870s when the Secretary of War selected an upright slab with a gently rounded top for known dead, and a small, low block for unknowns. The policy of accommodating only Union soldiers was shaped by wartime practice. Since the Union won the war, the Union would only take responsibility for burying its own soldiers in national cemeteries. Confederate burials fell to local communities. After the turn of the century, peacetime policies led to the inclusion of Confederate dead in military cemeteries. Memorials honoring groups of soldiers or military achievements were erected in national cemeteries, as well as in other community settings. Veteran organizations and the federal government erected these memorials to preserve the legacy of military accomplishment and the sacrifices made by America's soldiers throughout our history. Today, the 131 national cemeteries are managed by different agencies of the federal government, depending in part upon their history and activity: the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) within the Department of Veteran Affairs manages 120 and builds new ones; the National Park Service manages 14 affiliated with historic battlefields; and the U.S. Army operates two, including Arlington National Cemetery.

¹ America's Wars (Washington, D.C.: Veteran's Administration Office of Public and Consumer Affairs, 1985).

Locating the Site

Map 1: National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Veterans.

Questions for Map 1

1. How would you describe the geographic dispersion of soldiers' homes across the country? Why do you think the majority of the homes are in one half of the country?

2. Dayton became the largest branch of the soldiers' homes. What might explain this?

Locating the Site

Map 2: Site plan for Dayton National Cemetery.

(Courtesy of U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs)

The letters and numbers noted on the site plan identify the burial sections within the cemetery. Each interment (burial) is identified by section and grave number, for example: Section 7, Grave 23.

Questions for Map 2

1. What factors influenced the layout and boundaries of the cemetery?

2. Locate Monument Avenue where one would find the Dayton Soldiers Memorial. How would you describe its location?

3. In which section do you think the first burials took place? Why do you think so?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Soldiers' Home

In March 1865, President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill to provide care for volunteer soldiers who were disabled through loss of limb, wounds, disease, or injury during service in the Union forces during the Civil War. Initially called the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the name was later changed to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers because of the negative connotation of the word "asylum." The first three homes opened in Togus, Maine; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Dayton, Ohio. Eventually, there were 11 National Home branches across the country. Requirements for admission were that soldiers had been honorably discharged from military service and that they had contracted their disabilities during the war. Men admitted themselves to the home voluntarily and could request a discharge. The homes were run in a military fashion: men wore uniforms and were assigned to companies; bugles and cannons signaled daily schedules. The homes provided schools, churches, hospitals, and gardens thought to be therapeutic for the veterans.

In 1867, the government purchased land and began construction on the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Dayton. By 1868, the Central Branch was equipped to care for 1000 disabled soldiers. As the campus grew, it eventually covered 627 acres, complete with living quarters, hospital, library, and chapel. It was constructed in part using lumber recycled from the nearby Camp Chase where Confederate POWs had been confined. By 1884, the Dayton Soldiers' Home, as it became known, had become the largest of its kind in operation, accounting for 64% of the veterans receiving U.S. government institutional care. Dayton's veteran population reflected the diversity found in the Union Army, including black veterans, who the Dayton Home was the first federal institution to admit. More than 200,000 African-American soldiers and sailors served in the Union military, and many went on to serve on cemetery details after fighting ceased. The Dayton Home was progressive in other ways, as well. It operated according to the philosophy that exercise, reading, music, healthcare, and occupational training in preparation for reentering society-all taking place in a picturesque environment-would improve the health and wellbeing of the veterans under its care. Modern innovations included steam heat, indoor plumbing, and elevators.

Henry Howe described the Dayton home in his Historical Collections of Ohio:

The SOLDIERS' HOME at Dayton, the Central Branch, is by far the largest and most important branch in point of numbers. The citizens contributed $20,000 towards its establishment. Its land area is 627 acres -- nearly that of a mile square. Its location is three miles west of the court-house in Dayton, on the gentle bounding slopes of the great Miami valley, which is here some five or six miles wide. It is a unique place; a small city mainly of graybearded men, few women, and no children, excepting those of the families of the officers. It is a spot of great beauty, from its location, its fine buildings, its green-houses, flowers beds, and for the display of the triumphs of landscape gardening. These features render it a great place of attraction in summer for visitors, who come by thousands in excursion trains from all parts of Ohio and the adjacent States of Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, etc. The other Branches have like attractions in the way of landscape adornments with pleasant walks and drives, and whatever contributes to the comfort of the veterans, and are like places of resort for the public. The visitors at the Dayton Home number annually over 100,000.¹

In 1930, the federal government consolidated veteran benefits under a single agency, the Veterans Administration. National Soldiers' Homes continued run into the 1930s when the Veterans Administration took them over. The homes also housed veterans from the Spanish-American War and World War I. By the beginning of World War II, the soldiers' homes were phased out due to the high cost of hospital care and the fact that veterans were receiving medical treatment and returning to civilian life rather than staying at the homes. Today, the Dayton campus houses the Dayton National Cemetery and the Veteran Affairs Medical Center, which provides important medical care and out-reach services. It is operated by the Veterans Health Administration of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Questions for Reading 1

1. For whom and what purpose were the national soldiers' homes designed? How many were eventually established? If needed, refer to Map 1.

2. Why might the term "asylum" have negative connotations?

3. Why was the Dayton home considered progressive? Which group of veterans was the Dayton Home the first federal institution to admit? Why was that significant?

4. What kind of environment and what services did the Dayton Soldiers' Home provide? Were soldiers expected to spend the rest of their lives there?

5. Why do you think the home attracted so many visitors? Would you enjoy visiting a place like this? Why or why not?

6. Why were soldiers' homes phased out? How do you think the role of the Veteran Affairs Medical Center differs from that of the soldiers' homes?

¹ Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio in two volumes (Cincinnati, Ohio: C.J. Krehbiel & Co., 1888), 286.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Dayton National Cemetery

On July 17, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation that created the National Cemetery system. By 1870, nearly 300,000 Union soldiers were interred in 73 national cemeteries, many of which were located on or near battlefields. At that time, approximately 58% of these soldiers' graves were of known soldiers and the remaining 42% more were marked as unknowns.

Of the nearly 253,000 estimated Union dead in need of grave markers after the Civil War, about 105,000 were for unknowns-individuals whose identities were lost during the relocation process. More than seven years of debate over the design for a permanent headstone included the study of a cast-iron model that was eventually rejected as both unattractive and impermanent. The graves of unknown soldiers are marked with a 6 in. x 6 in. marble block that extends 30" deep, identified with a number only. The grave markers of the known dead-marble uprights measuring 12 in. high (above ground) x 10 in. wide x 4 in. thick with a slightly rounded top-are inscribed with a recessed federal shield in which the name, rank or affiliation appear in relief. Headstones of the regular Army and the U.S. Colored Troops have "USA" or "USCT" inscribed on them rather than state information. Men were assumed to be the rank of private if no record was available; therefore "PVT" was omitted from the inscriptions. Abbreviations such as this were necessary due to limited space.

Dayton National Cemetery is one of 11 federal cemeteries historically affiliated with National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Enrollment at the Central Branch climbed in the first 20 years to nearly 5,000 veterans by 1888. During the same period, 3,000 Union veterans were interred in the cemetery. Included among these veterans are over 650 African Americans who served in the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), making this cemetery one of the nation's largest burial sites for black Civil War soldiers. Nearly 10 percent of all Union soldiers were black. The first interment was of Corporal Cornelius Solly, 104th Pennsylvania Infantry, on September 11, 1867 (Section A, Row 12). Erected in 1873, the massive Soldiers Monument, a 30 foot-tall marble column with four figures at the base and a standing soldier on top, dominates the cemetery landscape.

The design of the Central Branch cemetery is attributed to Chaplain (and Captain) William B. Earnshaw, who had "judgment and taste" in the matter of cemetery layout and design. The rectilinear, grid-based symmetry of the cemetery may be based on familiar bivouac and camp arrangements. Earnshaw served in the Armies of the Potomac and the Cumberland, for which he was named superintendent at Stones River and Nashville national cemeteries. He also helped select sites for the Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Corinth and Memphis national cemeteries. With labor provided by the USCT, he was responsible for locating, disinterring, and reinterring the remains of 22,000 dead soldiers. "Disagreeable, offensive, and dangerous as was this work of love," Earnshaw led "his detail of colored troops, with spade in one hand and musket in the other.…"¹

Soldiers' home cemeteries were to be "laid out and cared for, as far as practicable, in the manner prescribed for National Cemeteries" and "graves shall be arranged in sections and rows and numbered in regular series to correspond with the burial record kept in the Headquarters' office." Administrators initially marked graves with the standard "temporary wooden board or tablet, giving name, company, regiment and date of death." Eventually, the monetary cost of marking graves became a factor within the U.S. government's budget. On a semi-annual basis the governors of each branch requisitioned permanent headstones from the Office of the Quartermaster General, which supplied all government-issued veteran headstones starting in the mid 1870s.²

Among the permanent improvements to the home in 1887 was the completion of a "new receiving vault connected with the hospital," which was a "very great convenience to the institution, as it enables us to hold in safety subjects for interment…" Every resident was to be buried in a "clean suit of the Home uniform."³ National Home regulations specified that "funerals will be conducted in accordance with military usage," with a chaplain officiating. "The band of the Branch will attend all funerals, unless the weather is too inclement. . . and the drum corps or field music substituted."4

Soldiers' Home cemeteries still provide their valuable service today, providing a final resting place for veterans. Since its beginning, Dayton's cemetery has grown to 110 acres and it contains the remains of veterans from the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Spanish American War, and all 20th century military conflicts. Approximately 800 burials are made annually, and the cemetery is slated to remain open to burials until 2018.5 The Veterans Administration (VA) assumed oversight of the cemetery in 1930. In 1973, it was granted National Cemetery status. Today it is operated by the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) of the VA.

Questions for Reading 2

1. How many cemeteries were established in the first nine years after President Lincoln signed legislation creating the system?

2. Why were cast iron headstones rejected? What material was selected instead? Do you think it was a good choice? Why or why not?

3. When the Union dead were interred permanently in national cemeteries during the late 1860s, it was the second time they were buried. The first was immediately after they were killed in battle and buried where they fell, or they died of disease in a hospital and were buried locally. Immediately after the war, these remains were located, disinterred, and moved to the new national cemeteries. What system was used to undertake this work and who was responsible for this unpleasant task? What does that imply?

4. Who manages the cemetery in Dayton today? When was it granted "National Cemetery" status?

¹ George Washington Williams, "The Soldiers' Home: Its Officers and Men," The Cincinnati Commercial, 24 November 1878.

² Regulations for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (no publisher given), 100.

³ U.S. Congress, House, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Annual Report of Central Branch, National home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers for the year ending June 30, 1887. 50th Congress, 1st session. Misc. Doc. 86, pp. 31-32; Regulations for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (no publisher given), 99.

4 Regulations for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (no publisher given), 99.

5 National Cemetery Administration, 2004.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Union Soldiers & Burial Practices

The following are a series of readings on the evolution of burial practices for U.S. soldiers. Today's burial policies have their roots in this period.

Excerpt from War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series III, Volume 1 (Washington: GPO, 1880-1901), 498.

GENERAL ORDERS No. 75

WAR DEPT., ADJT GENERAL'S OFFICE,

Washington, September 11, 1861

The following order has been received from the War Department, and is published for the information of all concerned:

WAR DEPARTMENT, September 9, 1861

For the purpose of preserving accurate and permanent records of deceased soldiers and their place of burial, it is hereby ordered that the Quartermaster-General of the U.S. Army shall cause to be printed and to be placed in every general and post hospital of the Army blank books and forms corresponding with the accompanying duplicate forms of preserving said records. The Quartermaster will also provide proper means for a registered headboard, to be secured at the head of each soldier's grave, as directed in the following special order to commanding officers in reference to the interment of deceased soldiers:

It is hereby ordered that whenever any soldier of officer of the U.S. Army dies it shall be the duty of the commanding officer of the military corps or department in which such person dies to cause the regulation and forms provided in the foregoing directions to the Quartermaster-General to be properly executed.

It is also ordered that any adjutant or acting adjutant (or commander) of a military post or company, immediately upon the reception of a copy of any mortuary record from a military company, shall transmit the same to the Adjutant-General at Washington.

By order:

SIMON CAMERON, Secretary of War.

L. THOMAS, Adjutant-General.

Excerpt from "War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies," Series III, Volume 5 (Washington: GPO, 1880-1901), 318-319.

QUARTERMASTER-GENERAL'S OFFICE,

Washington, D.C., October 31, 1865.

…The coffins now issued cost less then one-half the price paid by contract and are far superior. The hearses used for transportation to the graves are covered ambulances, painted black, and are well suited for the purpose. The tablets or head-boards are principally of white pine, with the exception of some 4,000 of black walnut, purchased more than two years ago. They are painted in white and lettered black, with the name, company, regiment, and date of death. I would here remark that unless tablets are painted before lettering the wood will absorb the oil in the paint and the rain soon wash off the lead in the lettering…

Extract from annual report of Capt. J. M. Moore, Assistant Quartermaster, U.S. Army, for the year ending June 30, 1865.

Washington, D.C.

Excerpt from "War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies," Series III, Volume 5 (Washington: GPO, 1880-1901), 1038-1039.

November 14, 1866

Mr. President

…Forty-one national military cemeteries have been established, and into these had already been gathered, on June 30, the remains of 104,526 Union soldiers. The sites for ten additional cemeteries have been selected, and the work upon them, for some time delayed by the climate and a threatened epidemic, is now in course of vigorous prosecution. Although it may not be desirable to remove the remains of those now reposing in other suitable burial grounds, it is estimated that our national cemeteries will be required to receive and protect the remains of 249,397 patriotic soldiers whose lives were sacrificed in defense of our national existence. The average cost of the removals and reinterments already accomplished is reported at $9.75, amounting in the aggregate to $1,144,791, and it is believed that an additional expenditure of $1,609,294 will be necessary. It is proposed, instead of the wooden headboards heretofore used, to erect at the graves small monuments of cast iron, suitably protected by zinc coating against rust. Six lists of the dead, containing 32,666 names have been published by the Quartermaster-General, and others will be issued as rapidly as they can be prepared…

Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War

Excerpt from a report prepared by D.W. Tolford for Ohio Governor Jacob D. Cox. Report relative to Union Officers and Soldiers buried in the vicinity of the late Principal Camps, Posts and Hospitals in the State of Ohio. Columbus, Ohio: December 12th, 1866.

…There are in the State many widows, orphans, and relatives and friends of deceased soldiers, who only know that members of their families left them to stand by the republic in its hour of need--that they were, from time to time, heard from upon some distant march--in hospital--upon the eve of battle--or in Southern prisons--and that they are dead! But where the remains have been buried-how-how protected; whether in a condition to be identified, or their graves even recognized as those of Union soldiers, are to them unknown things…

D.W. Tolford

Ohio State Soldiers' Home

Columbus, O., Dec. 12, 1866

Excerpt from Congressional legislation 1872. 57th Congress, 2nd Session. Report No. 2589. Marking the graves of the soldiers of the Confederate Army and Navy (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1903.)

Be it enacted, etc., That section one of an act entitled "An act to establish and to protect national cemeteries," (P.L. 37) approved February 22nd, 1867, be amended as follows:

The Secretary of War shall cause each grave to be marked with a small headstone, with the name of the soldier and the name of his State inscribed thereon, when the same are known, in addition to the number required to be inscribed by said section; and he shall, within ninety days from the passage of this act, advertise for sealed proposals of bids for the making and erection of such headstones, which advertisements shall be made for sixty days successively in at least twenty newspapers of general circulation in the United States, and shall call for bids for the doing of said work, in whole or in part; and upon the opening of such bids the Secretary of War shall, without delay, award the contracts for said work to the lowest responsible bidder or bidders, in whole or in part; and said bidders shall give bond to his satisfaction for the faithful completion of the work.

Approved June 8, 1872; General Orders, No. 65, AGO, 1872.

…Appropriated to provide for the erection of headstones upon the graves of soldiers in the national cemeteries, $200,000…..

Act approved June 10, 1872; General Orders, No. 52, AGO, 1872.

Questions for Reading 3

1. General Orders No. 75 represents one of the earliest statements on marking graves. The term used is "headboard." What does it mean? What problem does Captain Moore point out with the use of headboards?

2. By 1865, Secretary of War Stanton is proposing what change in soldier's grave markers?

3. The 1872 legislation amending the 1867 Act to establish and to protect national cemeteries once and for all determines the type of mark the graves of Union soldiers. What type(s) do they determine?

4. Why do you think it was important for the U.S. government to relocate soldiers already buried to centralized locations?

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: "Bivouac of the Dead" by Theodore O'Hara

Poet and Mexican War veteran Theodore O'Hara, who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War, wrote the poem "Bivouac of the Dead". Although written in the mid 1850s about the Battle of Buena Vista during the Mexican War, the verse was extremely popular during and after the Civil War. As a result, key stanzas, including these (1, 2, 11, 12), were cast in metal and placed in the national cemeteries. The words also appear on many individual memorials in the North and South. The poem is 12 stanzas in its entirety.

Dayton National Cemetery is one of a small number of national cemeteries that still have the original Bivouac of the Dead tablets cast at the Rock Island Arsenal.

Stanza 1.

The muffled drum's sad roll has beat

The soldier's last tattoo;

No more on life's parade shall meet

That brave and fallen few.

On Fame's eternal camping-ground

Their silent tents are spread,

And Glory guards, with solemn round,

The bivouac of the dead.

Stanza 2.

No rumor of the foe's advance

Now swells upon the wind;

No troubled thought at midnight haunts

Of loved ones left behind;

No vision of the morrow's strife

The warrior's dream alarms;

No braying horn nor screaming fife

At dawn shall call to arms.

Stanza 11.

Rest on, embalmed and sainted dead!

Dear as the blood ye gave;

No impious footstep shall here tread

The herbage of your grave;

Nor shall your glory be forgot

While fame her records keeps,

Or Honor points the hallowed spot

Where Valor proudly sleeps.

Stanza 12.

Yon marble minstrel's voiceless stone

In deathless song shall tell,

When many a vanished ago hath flown,

The story how ye fell;

Nor wreck, nor change, nor winter's blight,

Nor Time's remorseless doom.

Shall dim one ray of glory's light

That gilds your deathless tomb.

Questions for Reading 4

1. O'Hara was not publicly credited for the poem in the national cemeteries. Why might this have been?

2. What is it about this poem would account for its long-term popularity, in which the patriotic sentiments of the Mexican War also applied to the Civil War and transcend issues of politics or foe?

3. Explain how military elements and terminology are used to evoke feelings of heroism, valor, patriotism, sacrifice and loss in a cemetery setting.

4. Many of the original castings of "Bivouac of the Dead" have been removed. Why was this poems' message more poignant 100 years ago? Can you think of a contemporary source that may have a similar message?

Visual Evidence

Illustrations 1a & 1b: Letter from the Secretary of War regarding permanent grave markers.

The hand-written document pictured here is a portion of a letter from Secretary of War W.W. Belknap to Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs on June 23, 1873, stating his selection of permanent headstone to mark the graves of known and unknown veterans.

Questions for Illustrations 1a & 1b

1. What were some considerations relevant to the preparation and finish of the headstones/markers and the information on them?

2. What distinguishes the markers for the known dead compared to the unknown dead?

3. What might a cemetery's latitude have to do with the dimension of headstones?

Transcript: Letter from the Secretary of War regarding permanent grave markers.

War Department

June 25th 1873

General:

I have decided to adopt the following described headstones for the National Cemeteries -

Viz;

For the Known.

A white marble, or gray granite, slab four (4") inches thick - ten (10") inches wide, twelve (12") inches high above ground and, for the latitude of Washington and South, twenty-four (24") inches in the ground -- north of that latitude, thirty (30") in the ground.

The part above ground to be polished neatly and to have the top slightly curved.

The number of the grave, the rank and name of the soldier, and the name of the state from which he came, to be cut on one face - the figures and capital letters to be 2 inches long and 1/3 inch deep; the other letters one inch long and 1/3 inch deep. The letters may be in relief, or incised, at the option of the bidder.

The portion below ground to be rough dressed, and at least ½ inch wider and thicker than the part above ground. The bottom to be straight, and of uniform thickness, and the corners square.

For the Unknown.

A granite, or marble, block six inches square and two and a half feet long - 6" x 6" x 2'-6" -

The top and four inches of the sides of the upper end to be neatly dressed, and the number of the grave cut on the top in figures 2 ½ inches long and ½ inch deep. When the figures are more than three, they will be arranged in a curve around the margin.

The top to be flat, or, slightly convex. The bottom to be flat and full six inches square - the rest of the block to be rough dressed, or split, but to be of full size throughout.

The block to be firmly set in the ground so that the top shall be just even with the top of the grave.

The marble for the slabs to be white, of fine grain, good texture, and hard; For the blocks to be nearly white of pretty fine grain and good texture - to be a good durable marble.

Visual Evidence

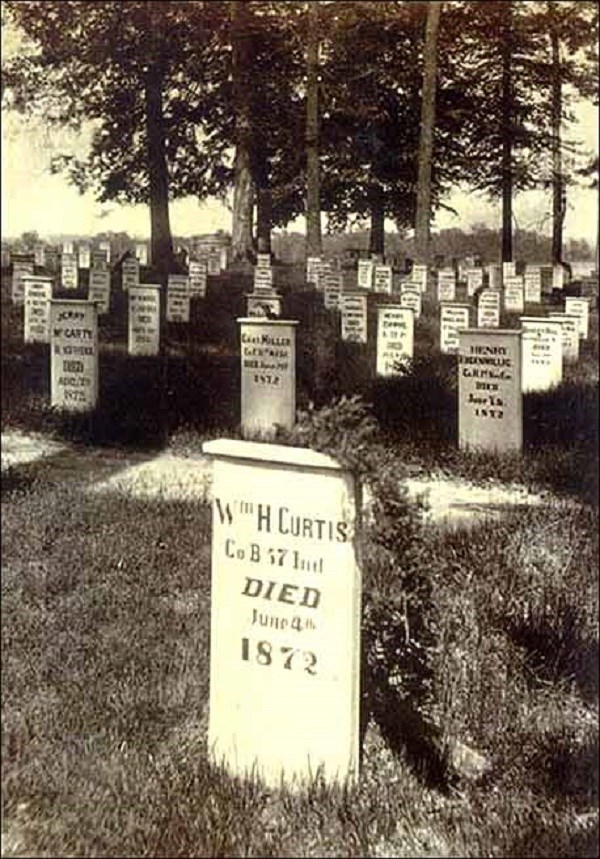

Photo 1: Historic image of grave marker, c. 1870.

(Courtesy of Dayton Veterans Affairs Archive)

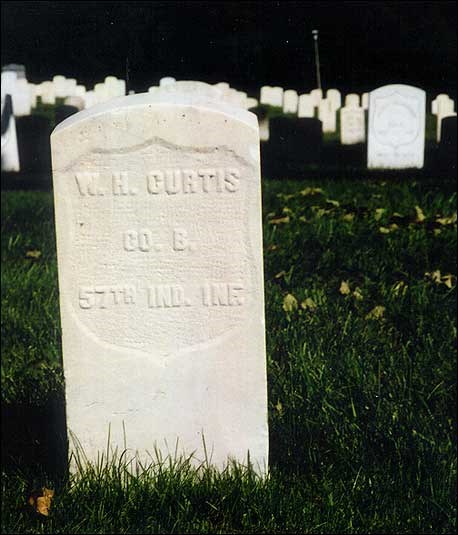

Photo 2: Present-day photo of grave marker.

(Courtesy of U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs)

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Compare the descriptions in Illustration 1 to Photos 1 & 2. Which grave marker matches the description given in Illustration 1? Describe how it matches.

2. Compare Photos 1 & 2. What are the differences in the grave markers? Why do you think the markers were changed?

3. What is the long-term problem with the marker in Photo 1? How might this problem add to the number of unknown soldiers graves?

4. What can the markers tell us about these soldiers?

5. Have you seen similar markers in a local cemetery? Are they associated with veterans? Which war did they serve in? How can you tell?

(Courtesy of Dayton Veterans Affairs Archive)

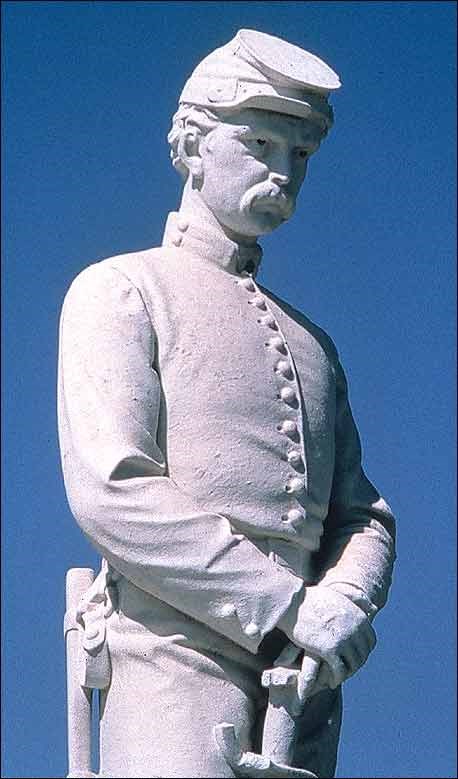

Photo 4: Detail of Dayton Soldiers Memorial.

(Courtesy of Dayton Veterans Affairs Archive)

The cornerstone of the Dayton Soldiers Memorial was placed on July 4, 1873, and the completed monument was dedicated September 12, 1877. President Rutherford B. Hayes delivered the dedication address before a crowd of 20,000. The 30 ft. column was designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe for the Bank of Pennsylvania.¹ After the building was demolished, the column was used in the creation of the Dayton Soldiers Memorial. Latrobe worked on the U.S. Capitol building and is credited with introducing Greek Revival architecture to America. A single figure of a soldier stands at the top, and four figures at its base represent Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery and Navy.

Questions for Photos 3 & 4

1. Examine Photos 3 & 4. What do you think the monument was meant to convey to the observer? What particular physical components (figures, symbols, structural components, and materials) convey the monument's message?

2. What does the monument's association with notable figures such as architect Latrobe and President Hayes tell you about its importance to the American public?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Aerial view of Dayton National Cemetery.

(Courtesy of U.S Department of Veterans Affairs)

Questions for Photo 5

1. What catches your eye in the aerial view? Why?

2. Compare this view of the cemetery with Map 2. Which image gives you a better feel for the size and design of the cemetery? Why?

3. How does its layout compare to other cemeteries you have seen?

Putting It All Together

The creation of soldiers' homes and grave markers helped honor Civil War veterans and preserve their legacy. The policies created after the war to deal with veteran issues are still in place today. The following activities will help students understand how and why these policies evolved and see their effects in their own communities.

Activity 1: African Americans in the Civil War

Joshua Dunbar, father of famous African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, is buried in the Dayton National Cemetery. Born into slavery, Joshua escaped slavery and, through the Underground Railroad, came to Ohio on the way to Canada. When the war began, he returned to Ohio, and then traveled to Massachusetts to join the Massachusetts 55th; he later served in the Massachusetts 5th Colored Cavalry.

Divide your class into three sections assigning each section one of the following activities:

a. Have students research Joshua Dunbar's story, write a biography about his life, and present it to the class.

b. Joshua Dunbar had a profound impact on the writings of his son, Paul Laurence Dunbar who wrote The Colored Soldiers, The Unsung Heroes, and Our Martyred Soldiers. Have students study the following excerpts from The Colored Soldiers and then lead a class discussion including some of these questions: When was this written? What was the "status" of African Americans in American society during this time? What message was Dunbar trying to convey? Do you think African American contributions to the Civil War were appreciated? Why or why not?

…They were comrades then and brothers,

Are they more or less to-day?

They were good to stop a bullet

And to front the fearful fray.

They were citizens and soldiers,

When rebellion raised its head;

And the traits that made them worthy,--

Ah! those virtues are not dead. …… And their deeds shall find a record

In their registry of Fame;

For their blood has cleansed completely

Every blot of Slavery's shame.

So all honor and all glory

To those noble sons of Ham--

The gallant colored soldiers

Who fought for Uncle Sam!

c. Research the contributions of American-American soldiers to the Civil War and report to the class.

Activity 2: Explore Your Community for Memorials

Have students locate and visit a war memorial in your community. Students should create an exhibit for the school that addresses the following questions, and include visuals to illustrate their points:

Who or what is being recognized by the memorial and why?

What war is memorialized?

Who erected the memorial?

Where is it?

Why do you think your community has the memorial?

Did they play a particular part in the war effort? If so, what?

What is the physical condition of the memorial?

Does it need to be repaired or "conserved" by a historic preservation professional?

If so, prepare a letter to the city or local historical society asking them for help in preserving this piece of history.

Activity 3: Local Cemeteries

Have students inventory the veteran gravesites in your local cemetery. Students should use cemetery records and undertake a physical search. Do the records and the physical evidence agree? How many veteran graves are interred here? Are there any unmarked graves? What is the physical condition of the markers? Assign one or more of the following activities:

a. Create a database and status report on the markers and present it to the appropriate caretaker of the cemetery.

b. Research how to clean and care for an historic gravestone or marker. Contact your State Historic Preservation Office and/or the Association for Gravestone Studies to learn what techniques, cleaning solutions and tools are appropriate-and what not to do to avoid damaging the stone. Volunteer to help clean the headstones or help with the grounds upkeep.

Activity 4: A Soldier's Life

Have students research the life of a war veteran for whom you have located a headstone, or select an ancestor who served in a war. Students should create a biography of the soldier's life from birth through the war, to his or her final resting point in the cemetery. Donate the biography to the local historical society or library so their story can be preserved for future generations.

Some research sources include:

a. Cemetery Association Records

b. Headstone Inscription

c. Genealogy data (local library or genealogy organization)

d. Obituary notices in newspapers (on microfilm at library)

e. Local Historical Society records

f. Soldiers Military File (National Archives)

g. Soldiers Pension File (National Archives)

A Nation Repays Its Debt: The National Soldiers' Home and Cemetery in Dayton, OH--

Supplementary Resources

By studying A Nation Repays Its Debt: The National Soldiers' Home and Cemetery in Dayton students learn how the U.S. government cared for and honored its veterans by creating a system of soldiers' homes and national cemeteries. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Department of Veterans Affairs: National Cemetery Administration

The Department of Veterans Affairs is a useful web site for the family of veterans seeking information on national cemeteries, soldiers lots and related history. The site is also convenient for those searching for information eligibility of veterans for burial benefits and the government grave marker program.

Dayton Veteran's Affairs: Virtual Tour Museum

The Virtual Tour Museum showcases a host of photographs on exhibit displaying the cemetery, grounds and museum. The museum also displays pertinent information on preservation projects of the American Veterans Heritage Center and the history of the museum.

National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives (NARA) is a federal agency committed to the availability of government documents to the public. Included are documents related to the soldiers that served during the Civil War, such as military and pension files and articles pertaining to both soldiers' homes and the marking of veterans graves.

African American Civil War Memorial

This website includes a database with the names of African American Civil War Veterans. It also houses an extensive photo gallery, information for teachers hoping to use the information in lesson plans, and the history of the museum.

United States War Department:

The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies

This Cornell University database contains a massive amount of primary source data of both the Union and Confederate armies including: correspondence, official reports, orders, information on prisoners of war, state prisoners, political prisoners, and the reports of high ranking military officials.

Tags

- ohio history

- ohio

- veteran

- veteran care in the u.s.

- veteran graves

- disabled americans

- civil war

- civil war cemeteries

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- african american history

- military wartime history

- gilded age

- disability history

- military history

- veterans

- dayton

- mid 19th century

- early 20th century

- twhplp

- ga aah