Last updated: May 9, 2023

Article

The Tuskegee Airmen: Training and Stateside Experiences (Teaching with Historic Places)

Introduction

In World War II, the United States military was segregated, and African American service members faced discriminatory limitations in positions. The Army Air Corps was expanded by Public Law 18 in April 1939 and the demand for more pilots lead to the creation of the 99th Pursuit Squadron in 1941. In Tuskegee, Alabama, the U.S. Army Air Corp began a program to train African American servicemembers as Air Corps cadets. Instruction was provided by Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) and the U.S. Army. Flight training was provided primarily at Moton Field. African American pilots (about 1,000 aviators) and civilians in supporting operational roles (more than 15,000 persons) were involved in the efforts. By the end of the war, the Tuskegee Airmen had completed 1,578 combat missions, and the airmen received some of the highest honors in the Army Air Corps. The 99th Fighter Squadron (formerly known as the 99th Pursuit Squadron) would combine with the 100th, 301st and 302nd to form the 332nd Fighter Group. In 1998 Congress established the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Site. This lesson’s purpose is to connect students to the history of the place and the voices of servicemembers who trained there.

Objectives:

- Describe the role of Moton Airfield in training the Tuskegee Airmen

- Identify both the contributions of, and challenges faced by, the Tuskegee Airmen

- Connect the contributions of the Tuskegee Airmen to the integration of the U.S. military and the Civil Rights movement

About this Lesson

Includes authors, learning objectives, and materials for students

Getting Started: Essential Question

Photo 1: Tuskegee Airmen Cadets

Locating the Site

Photo 2: Hangar No. 1 at Moton Airfield

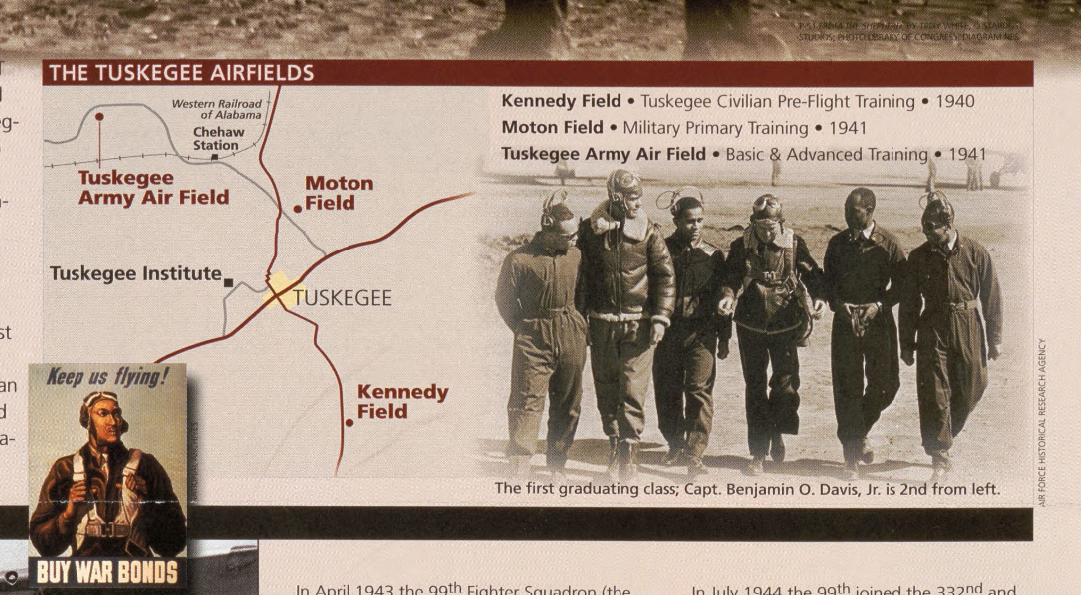

Map 1: The Tuskegee Airfields

Photo 3: Moton Airfield

Photo 4: Cadets in class

Determining the Facts with readings and visual evidence

Reading 1: Life in, and after, Tuskegee

Photo 5: Harry Leavell (“Veteran of the Day”)

Reading 2: Cecil Peterson’s Letters to Mrs. Roosevelt

Photo 6: Letter photograph

Photo 7: Cecil Peterson and Eleanor Roosevelt’s first meeting

Reading 3: “Job Just Begun”

Photos 8: The Jackson Advocate excerpt

Optional Activities

Activity 1: Voices of the Airmen

Activity 2: Propaganda

Photo 9: “Keep us Flying!” poster

Photo 10: “She’s a swell plane – give us more!” poster

Activity 3: The Hangars

Photo 11: P-51 Mustang "Red Tail” replica

Resources

The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site was established to commemorate the African American servicemembers who trained at Moton Field during WWII. Pilots, communication specialists, parachute riggers, navigators, and more trained at Tuskegee Institute (which supported the instructional programs) and Moton Field. The brave contributions of these African American servicemembers in a time of unfair discrimination helped to lead to the integration of the U.S. military and other civil rights advancements.

The lesson aims to connect students to the historical significance of the site by highlighting stories and voices of Tuskegee Airmen who trained at Moton Field. The lesson includes primary sources connected to the National Historic Site including photographs, oral history, letters, newspaper article, texts, and reflection, through questions and activities.

Some of the primary source documents reflect racial prejudices of the time. While offensive and insensitive, today’s readers can use this to understand the wrongful discrimination and opposition that the Tuskegee Airmen faced as African American pilots. Acceptance by the Army Air Forces was slow to come, and the servicemembers were segregated throughout the duration of the war. Finally, in 1948, President Truman ordered the desegregation of the United States military. This lesson was authored by Sarah (Nestor) Lane, educator.

1.) Map 1, Photos 1-11: To display digitally (or print copies). See also additional images under Resources.

Recommended: Distributed or displayed map of Alabama and/or Southern United States

2.) Readings 1-3, with Questions

3.) Art supplies, optional for activities 2 and 3

Note: Providing student copies of the written texts (ex. readings) to mark on (digitally, or print) can support the understanding of important themes appearing in oral history (qualitative research). For example, students can identify and notate, or highlight, to identify parts of an interview transcript that connect to broader themes/topics (discrimination, training at Tuskegee . . .) to support understanding of the essential question.

Time period: World War II

Topics: World War II, Tuskegee Airmen, segregation, Civil Rights

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

This lesson relates to the following National Standards for History from the UCLA National Center for History in the Schools:

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Standard 3: The causes and course of World War II, the character of the war at home and abroad, and its reshaping of the U.S. role in world affairs

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

This lesson relates to the following Curriculum Standards themes for Social Studies from the National Council for the Social Studies:

Theme 2: Time, Continuity, and Change

Theme 5: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

Theme 8: Science, Technology, and Society

Theme 9: Global Connections

Relevant Common Core Standards

This lesson relates to the following Common Core English and Language Arts Standards for History and Social Studies for middle and high school students:

Key Ideas and Details

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-12.1

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY. RH. 6-12.2

Craft and Structure

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-12.4

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-12.7

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-12.9

Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH. 6-12.10

Getting Started: Essential Question

How did the Tuskegee Airmen contribute to the Allied war effort, and in turn how did their experiences contribute to the advancement of Civil Rights in the United States?

Photo 1: Tuskegee Airmen Cadets

Source: AP Photo/U.S. Army Signal Corps [Credit: Library of Congress]

Locating the Site

Photo 2: Hangar No. 1 at Moton Airfield

NPS

Map 1: The Tuskegee Airfields

Photo 3: Moton Airfield

NPS

Photo 4: Cadets in class

Map 1 and Photos 3 & 4 Questions

1. Share what you already know about the South, Tuskegee, Alabama, and its surrounding sites of historical significance, leading up to, and at the time of, WWII. Use map 1, and optional teacher-provided maps of Alabama and/or the Southern United States, to guide your reflection.

2. Read the labels on the buildings in Photo 3. What type of buildings were needed to have a functional airfield? What buildings would have contributed to life for the cadets outside of training hours?

3. Look at photo 4: What do you notice and wonder? How does the photo caption contribute to your understanding of the context?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Life in, and after, Tuskegee

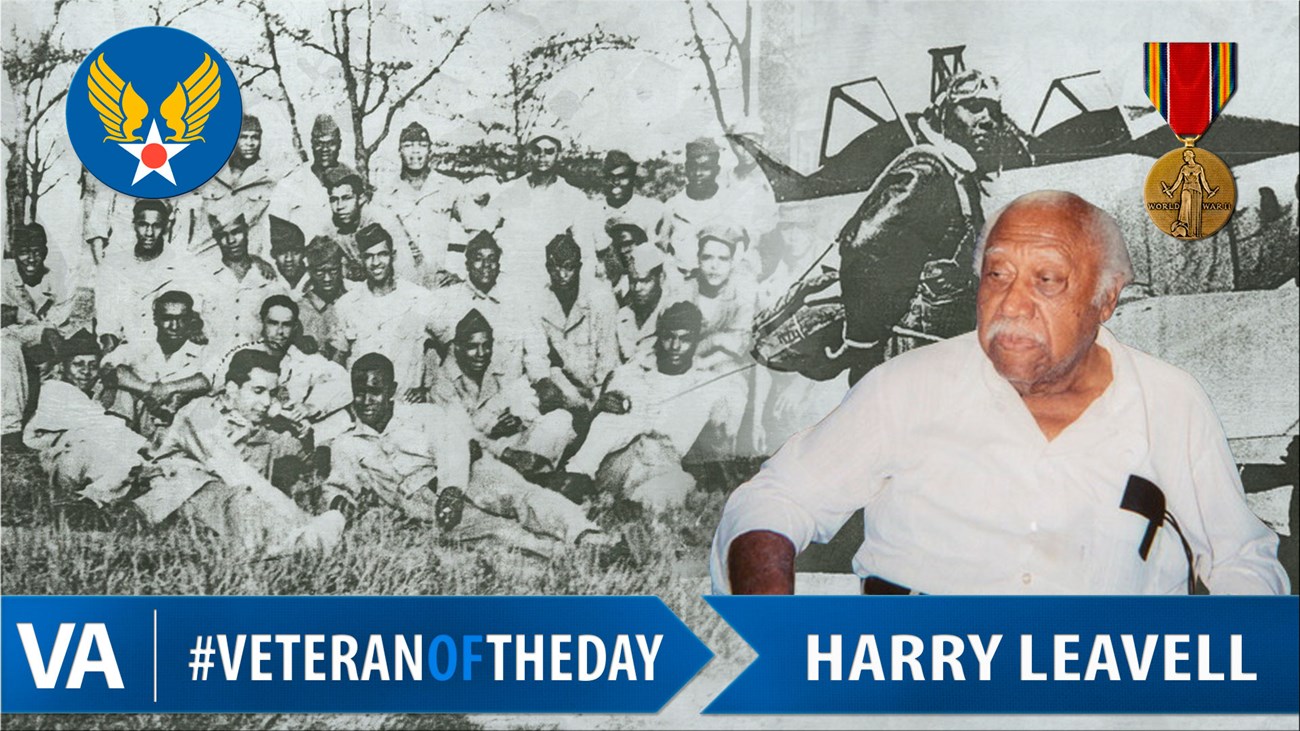

Background: Harry W. Leavell was one of over 2,000 African Americans who completed training at the Tuskegee Institute/Moton Airfield from 1941 to 1946. Those that trained there were known as the Tuskegee Airmen and would play critical roles in escorting bombers and shooting down enemy attack aircraft. Several Tuskegee Airmen would receive awards of the highest honors from the Army Air Corps.

Photo 5: Harry W. Leavell, “Veteran of the Day”

Excerpts from Interview with Harry W. Leavell [6/27/2002], Veterans History Project

Elizabeth Elsener, Interviewer (EE): …So how long were you at Tuskegee?

Harry W. Leavell (HL): . . . It was on campus for the basic college-training detachment, and we was supposed to be there five months, but there was a shortage, and we stayed three months. Then we went to -- from there back over to the base for preflight. And then we went from preflight back to the campus, and stayed in one of the dormitories, and that's called primary. Through a PT -- PT-19, and then the basic and advanced back on base. And so then they went through our record and found out we hadn't gone on a bivouac [guard, watch]. So one night they said "get ready, we're going on a bivouac." So we went out and stayed out that night. And, of course, you have gunnery. Now the fellows would go in, the fighter pilots, they trap shoot, and then they have -- there's a link trainer, and they have a gunnery, you know, you practice it. But one of my classmates (James Harvey)…you heard of a Top-Gun program?

EE: Yes.

HL: He was the first Top Gun.

EE: Really?

HL: A Black guy.

EE: The very first.

HL: The first top gun in the program. They were over in Columbus, Ohio at the time. At Lockbourne Air Force. He flew a P-47, and the governor wrote to B. O. Davis and tell him, you know, what honor they brought to the state of Ohio. And it was out at Las Vegas, and they walked in, they walked there, and they couldn't go in the hotel because they was black. And he was the first Top Gun. . . . I -- the job I had . . .they gave me a basic-entry job. . . pistol rings. And, you know, all of this education, you know, from the military, and they give me one of the worst jobs in the factory, and that -- I still gets angry about it, you know, but I wanted to go back to work, and I thought I would get, you know, a decent job . . .

EE: Wow. Well, where did you go from Tuskegee? When did you leave there?

HL: Well, let's see, I had a lot of misfortune, family misfortune, when I was there. When I was in preflight, my father took pneumonia, and he died. And I came home for a week, and I was able to catch up. And then when I was in basic, my mother had a heart attack, and I came home. And so then she got better then I went back, and then she died, and they worked me back a class. So I was in two classes, I was in 44-I and 44-J. And so as I came home, riding trains, and my wife and I tried to go to the theater one night, and couldn't buy a ticket, because there's no section -- no room in the black section, and then I -- you know, I got, I lost some of my nerve and zeal, you know. And so then they -- I wanted to be a fighter pilot, and I said, you know, I'll just go on to twin-engine. Twin-engine was located down here at Columbus -- Camp Atterbury. And a lot of those fellows that were there -- they were officers, and they wanted to go to the Officers' Club, and they wouldn't let them go. So they decided they was going to go anyway, and they court martialed them, and so anyone who tried to go to the Officers' Club they court martialed. So I was, I was glad in a way that I didn't go, you know, but, you know, then again I wanted -- I really wanted to do what I could, and I wanted to be a fighter pilot, and I wanted to go . . . but then I got into an engineer outfit, went down there -- left there and went to Tampa, Florida -- MacDill Field, and -- for re-assignment…

. . .

HL: . . .When we were down on at the college-training detachment, we had one of the fellows, I'm not sure who it was, but he was Catholic. And he was going to go to church, and so he left on Sunday morning, and we didn't see him for several days later. He came back, and his head was all bandaged up. And I guess he got on the bus, and he was supposed to go around and get on the back. But he didn't know, and this guy -- this driver hit him in the head with a hammer, and, of course, there's nothing you can say. That's -- that's what they said, that was it. Then after 11:00, you weren't allowed in Tuskegee, the town itself. You had to know the sheriff's name, but you better not be in town after 11:00 p.m.

. . .

HL: . . . And some of them, they didn't -- they didn't want you to succeed, and they did everything they could to keep you from succeeding. For example, there was a man named Major (Boyd) and Major Boyd said that you couldn't fly instruments if you had a mustache. Well, we had a number of men in our outfit who had mustaches. They were first lieutenants, second lieutenants, they were officers that came in for pilot training. And so we wondered, are they going to shave their mustaches off? But they shaved them off. But there was another fellow, a major, I think, I forget, major -- what his last name was, but he was taken off in a B-13, and the plane crashed, and he almost died. He needed some blood, and the only blood they had of that type was a black man. And his wife almost let him die rather than let him take that blood. And the man named (Drew) he's the man who developed the technique for blood plasma. And they tried to keep blood separated, you know, white blood separated. They said there's no difference, blood's blood, you know. Skin -- what makes people colored is called melanin, and keratin, everybody has it, some has more than others, you know. And there's something called plasticity of the human species. How you adapt to the environment, but, yeah, you know, his wife was going to let him die rather than take that transfusion.

Questions for Reading 1:

1. Highlight the text or describe examples of segregation and discrimination Leavell details in his accounts.

2. Describe the experiences of Leavell trying to reintegrate into the community, both as a servicemember and post-service citizen. What prior knowledge do you have about African American servicemembers returning home from service? How does Leavell’s experiences align or differ than what you had known?

3. How did the Tuskegee Airmen’s accomplishments contribute to the nation’s overall progress? (For example, consider the desegregation of the military in 1948, and the Civil Rights movement)

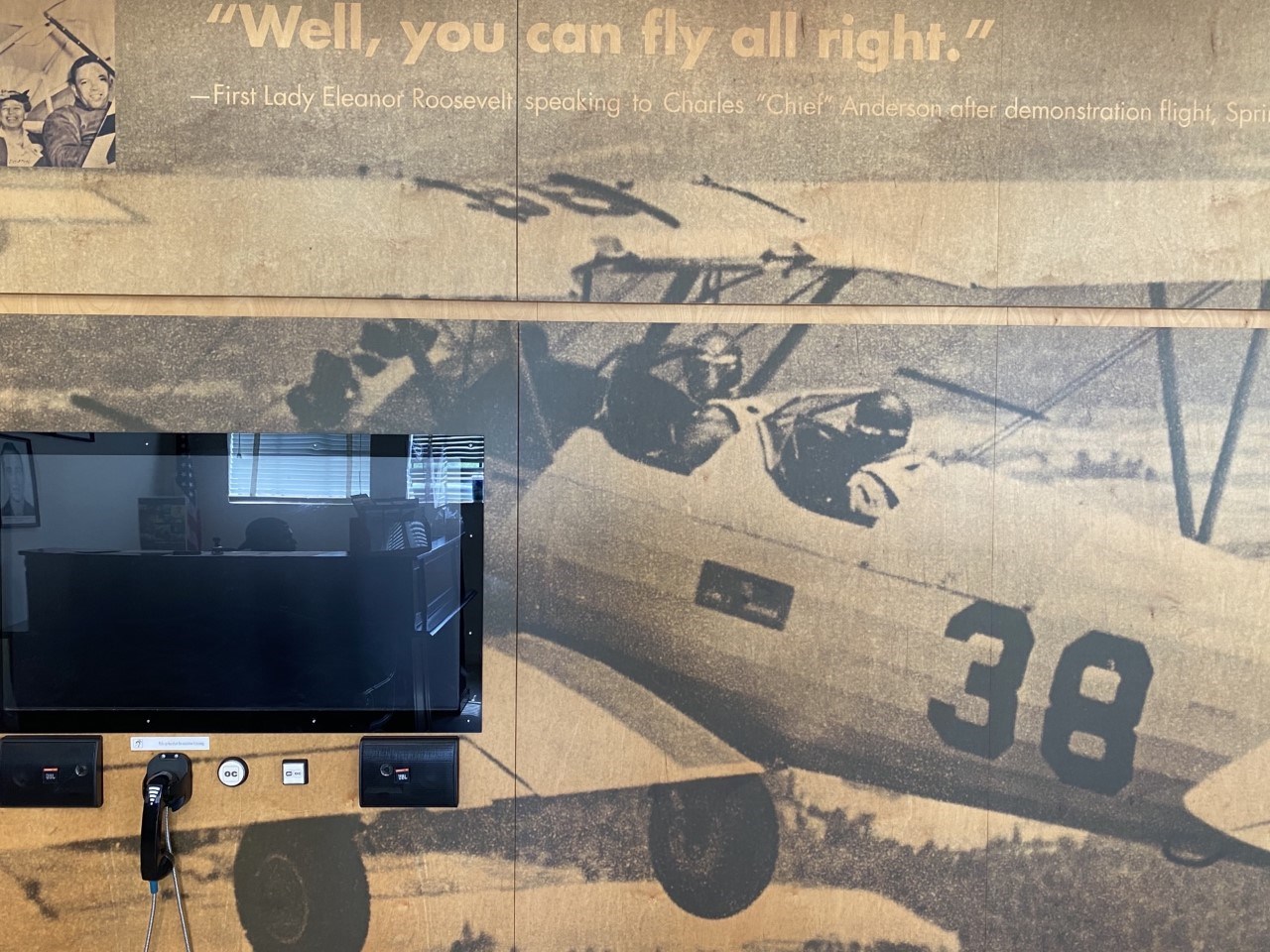

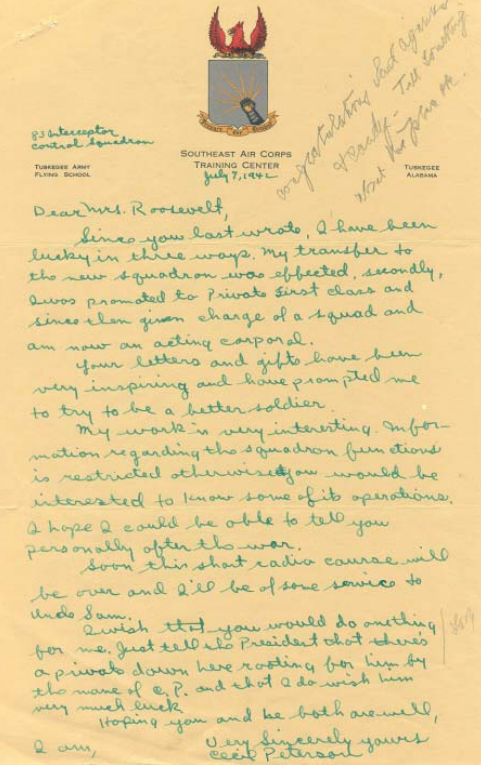

Reading 2: Cecil Peterson’s Letters to Mrs. Roosevelt

Background: First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Tuskegee Institute and went on a flight with Charles A. Anderson commonly known as Chief Anderson, a self-taught pilot. Anderson had established the civilian pilot training at the Institute in 1939. Mrs. Roosevelt was impressed by the program and maintained long-term friendships with some of the pilots. She was an advocate for the flying school. Cecil Peterson was one of those pilots that she had shared correspondence with.

Transcript:

Letter heading: Tuskegee Army Flying School; Southeast Air Corps Training Center; Tuskegee Alabama

July 7, 1942

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt,

Since your last words, I have been lucky in three ways. My transfer to the new squadron was effected, secondly, I was promoted to Private First Class and since then given change of a squad and am now an acting corporal.

Your letters and gifts have been very inspiring and have prompted me to try to be a better soldier.

My work is very interesting. Information regarding the squadron functions is restricted otherwise you would be interested to know some of its operations. I hope I could be able to tell you personally after this war.

Soon this short radio course will be over and I’ll be of some service to Uncle Sam.

I wish that you would do one thing for me. Just tell the President that there’s a private down here rooting for him by the name of C.P. and that I do wish him very much luck. Hoping you and he both are well, I am,

Very Sincerely yours,

Cecil Peterson

Photo 6:Letter from Cecil Peterson to Mrs. Roosevelt.

Photo 7: First Meeting of Cecil Peterson and Eleanor Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

Questions for Reading 1

1. How does Cecil describe his status?

2. How would you describe Cecil and his perspectives / outlook? Why?

3. What is historically and socially significant about Peterson’s ongoing correspondence with Mrs. Roosevelt?

Extension: To read more of Cecil Peterson’s letters, and Eleanor Roosevelt’s responses, refer to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

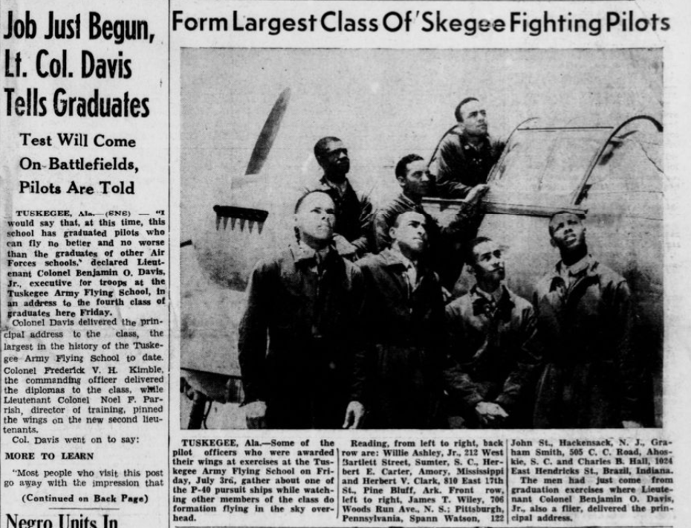

Reading 3: “Job Just Begun, Lt. Col. Davis Tells Graduates”

Transcript of excerpt from The Jackson Advocate (Jackson, Mississippi), July 11, 1942

Photo 8: 1942 Newspaper showing recent graduates.

Library of Congress

Transcript:

Job Just Begun, Lt. Col. Davis Tells Graduates

Test Will Come on Battlefields, Pilots are Told

Tuskegee, Ala. -- “I would say that, at this time, this school has graduated pilots who can fly no better and no worse than the graduates of other Air Forces schools,” declared Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., executive for troops at the Tuskegee Army Flying School, in an address to the fourth class of graduates here Friday.

Colonel Davis delivered the principal address to the class, the largest in the history of the Tuskegee Army Flying School to date. Colonel Frederick V.H. Kimble, the commanding officer delivered the diplomas to the class, while Lieutenant Colonel Noel F. parish, director of training, pinned the wings on the new second lieutenants.

Col. Davis went on to say:

More to Learn

“Most people who visit this post go away with the impression that we are over the hump, that the job is done. It is done in the same sense that you have a military pilot in an individual who can take an airplane off the ground and land it. So much has been demonstrated but this cannot be the complete answer. The only valid test of fighting unit is in its ability for itself in combat. So, understand then, that your work has begun. You are John Doe, second lieutenant, Army Air Forces, who knows something about military life and something about flying.

“You have a great deal to learn about administrative duties in your squadron. You have yet to learn to fly as a member of combat team in a fighting airplane. You must learn these things well in a short time. You have before you positions of great responsibility for which you must qualify yourself immediately. You and all the other early graduates of this school have the added burden of proving to all concerned that as military pilots you are as good as any in the world. It is true that your task is difficult and important, but it is my belief that you will accept the challenge and carry on in such manner that your record will be a credit to yourself and to your country.”

Highest Officer

Colonel Davis spoke to the graduates as one who had passed through the same stage. He was one of the members of the first class to graduate at this air base, back in March. At that time he was a captain. Today he is the highest ranking Negro officer in the Army Air Forces, being the only lieutenant colonel in that branch of the Army.

The invocation and benediction were delivered by First Lieutenant Douglass L.T. Robinson chaplain for the air base. Captain Roy F. Morse, secretary of the Ground School, handed the diplomas to the commanding officer, who in turn, game them to the graduates. Several hundred relatives and friends of the graduates thronged into the Post Theater for the exercises, some of them coming many hundreds of miles to witness the ceremonies.”

Questions for Reading 3

1. The title of the article reflects the quotation: “Most people who visit this post go away with the impression that we are over the hump, that the job is done.” Lt. Col. Davis went on to share that is not the complete answer. What job(s) do you think he is referring to, and why?

2. “You have before you positions of great responsibility for which you must qualify yourself immediately. You and all the other early graduates of this school have the added burden of proving to all concerned that as military pilots you are as good as any in the world.”

Although Lt. Col. Davis did not go into detail on the “added burden,” the graduates understood his implications. Describe the added burden(s) the Airmen faced entering the war and the meaningfulness of Davis sharing this at their commencement.

3. The Jackson Advocate is an African American newspaper, founded in 1938 and is still printed, with the mission of serving as “The Voice of Black Mississippians.” African American publications such as The Jackson Advocate produced their own news stories covering the war and servicemembers. Why were newspapers like the Jackson Advocate important at the time, and still important today?

Bonus: If time, try searching for news of the Tuskegee Airmen and/or Moton Field using the National Archives, Library of Congress, and/or other primary source search engines. Note and compare the number and quality of publications across the newspapers. What trends and themes do you notice?

Optional Activity 1: Voices of the Airmen

Extend on learning via oral history. Engage students in listening to / viewing an interview of a Tuskegee Airman, either as a class, in a small group, or individually.

Support students in noting the personal experiences of the airmen, and organizing their notes around themes and topics, such as: training and Moton Airfield and Tuskegee references, personal life and servicemember living, and sociocultural, historical issues of the time. You may also support students in learning more about the contributions of the Tuskegee Airmen abroad in this activity through firsthand accounts.

For accessing recorded interviews, you may refer to:

• Veterans History Project, Library of Congress recordings (audio, video) of veterans. Some also include written transcripts, like

• Tuskegee Airmen’s oral history collection (approximately 1,500 audio and video recordings) [Two collections: Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project (2002), and a second to support a documentary]

• Other documentaries and/or videos including firsthand account interviews

You can extend the experience from this activity through community service supporting students in interviewing, and documenting, the voice of veteran(s) in your community.

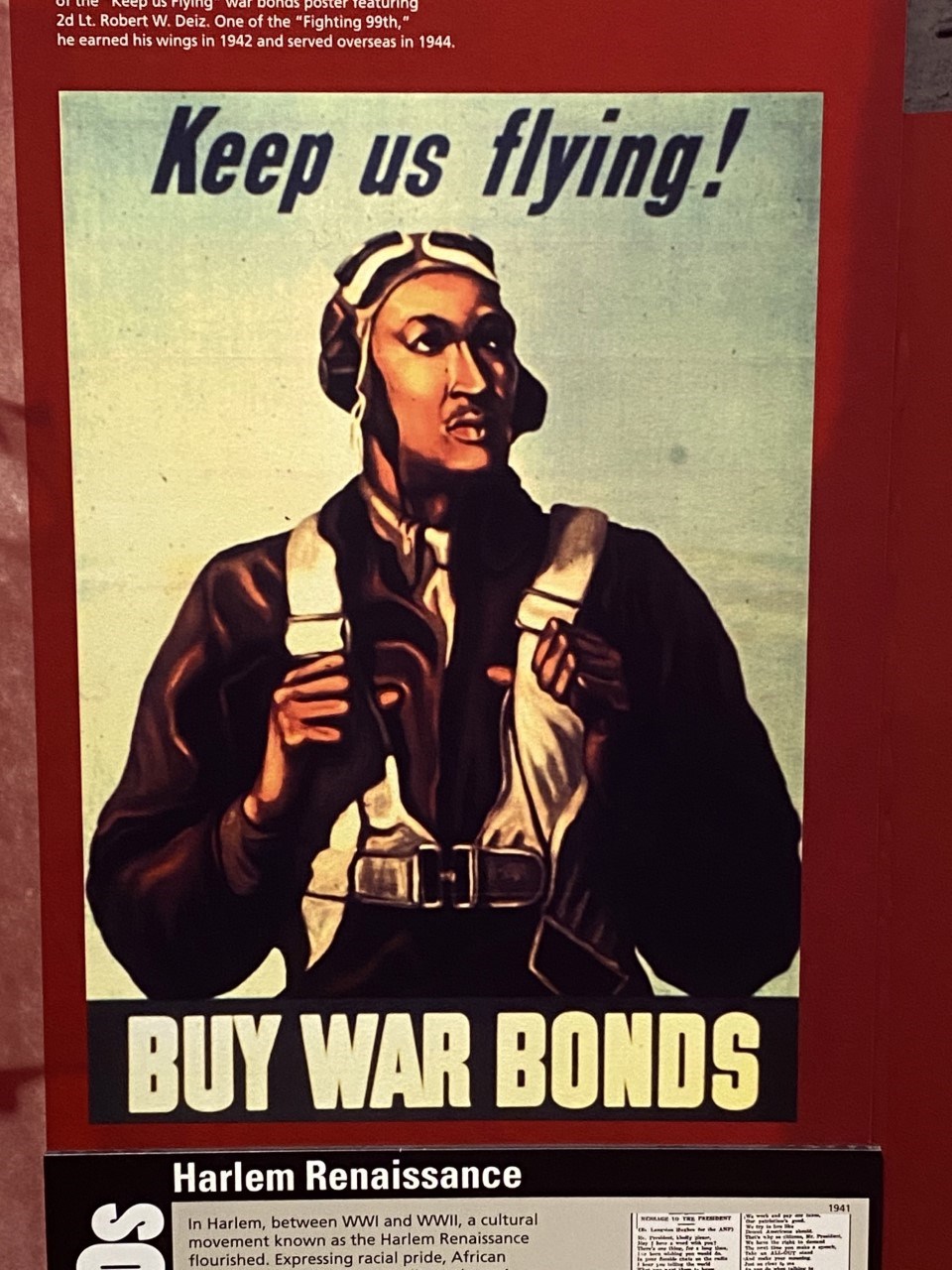

Optional Activity 2: Propaganda

Photo 9: Propaganda Poster featuring a Tuskegee Airman

NPS

Photo 10: Propaganda Poster promoting more production

War propaganda posters are historical artifacts that share a piece of the messages meant for home front civilians and future servicemembers, reflecting beliefs, needs, and attitudes of the time. The airmen from Tuskegee were featured in very limited propaganda pieces considering the high number of propaganda pieces produced. Have students analyze, critique, and reflect upon WWII propaganda that featured African American servicemembers, such as the Tuskegee airmen. Support students in reflecting and sharing about . . .

-

the intended audiences of propaganda, and how this impacted its design and distribution

-

the differences and similarities between propaganda featuring African American and white servicemembers (quantity, particularly)

-

how the portrayal of Tuskegee Airmen, and the sharing of their WWII successes (such as in radio, newspaper, and other media forms) (ex. Reading 2), contributed to the advancement of the desegregation of the military and advancement of Civil Rights

-

the role of media today: What has changed and stayed the same in relation to depicting civilian efforts in the war, and are the messages more inclusive today? What growth is yet to be made to reflect all servicemembers?

Optional extension: Students to create their own propaganda poster. It can start “from scratch” using artifacts as inspiration, or taking one previously made to redesign it to reflect inclusivity and diversity, showing the future of the U.S. military.The National Archives Collection of over 2,000 WWII propaganda pieces and can be used as a resource for this activity.

Optional Activity 3: The Hangars

Photo 11: Plane in the hangar exhibit

At the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Hangars No.1 and No. 2, have different topics and exhibits for visitors. Hangar No. 1 focuses on support personnel such as parachute riggers, mechanics, office staff, and civilian staff. Hangar No. 2 shares stories about the bomber and fighter pilots, and their experiences during and post-war. Both integrate the challenges of segregation and discrimination.

If possible, the best way to connect to these exhibits is to plan a trip in-person for your students! If visiting in-person, support students in taking notes of learning in each hangar, and the topics, themes included in them. However, with distance learners, support your students by listing the topics contained within each hangar’s exhibits. (One place to start to envision these places could be a blog post from a visitor’s perspective, such as this one by a CAF Red tail Squadron volunteer shares a short, personal perspective to help others imagine visiting Moton Field. A second helpful resource is this Tuskegee Airmen Virtual visit resource by NPS.)

Have students select a hangar (one topic, or multiple, housed within), and design an exhibit piece that could be displayed within that hangar.

Products could include: a poster, brochure, model, video, photo collage, artwork, an educational resource that could be used for younger audiences like the Junior Rangers program, or other creative product(s).

The product should: 1) answer the essential question of “How did the Tuskegee Airmen contribute to the Allied war effort, and in turn how did their experiences contribute to the advancement of Civil Rights in America?”; 2) include learning from across the lesson; and 3) include the opportunity for additional research by using resources like those listed below.

Resources

There are many resources to learning more about the Tuskegee Airmen. If able to visit the site, the giftshop sells a DVD called The Tuskegee Airmen Sacrifice and Triumph, that contains all oral histories from the display inside Hangar 2. [An excerpt is also included in the site’s orientation video.] Teachers can schedule virtual tours of the site as well, including a Q and A session with a ranger.

To support your students in extending their learning, here are examples of additional resources, in alphabetical order:

CAF Rise Above: Red Tail

National Museum of African American History & Culture

National Museum of the United States Air Force

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum: Black Wings

The National Museum of the Tuskegee Airmen

The National WWII Museum

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic SiteTuskegee Airmen National Historic Site Virtual Museum Exhibit

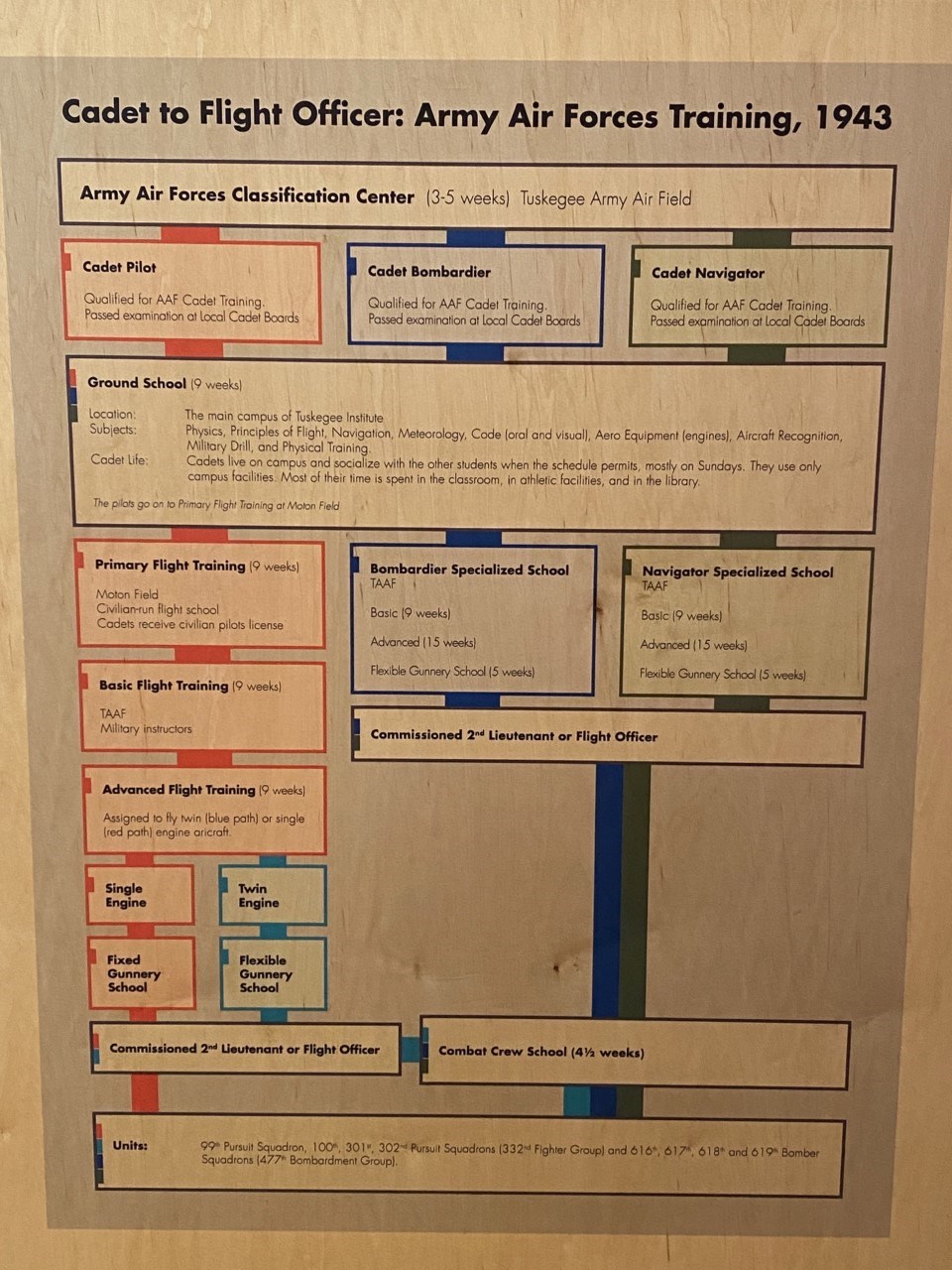

Additional Image: Training Steps from Cadet to Flight Officer

NPS

Additional Image: Eleanor Roosevelt quote featured in display

NPS

Tags

- tuskegee airmen national historic site

- tuskegee institute national historic site

- tuskegee airmen

- world war ii

- breaking barriers

- african american

- african american soldiers

- african american history

- aviation history

- civil rights

- aviation figures

- military aviation

- aviation firsts

- communication

- navigation

- science and technology

- technology

- black history

- twhp

- teaching with historic places

- alabama

- alabama history

- twhplp

- military history

- wwii aah

![“African American Army Air Force group at Tuskegee Army Air Field, Alabama] / Official Photo U.S.A.A.F. by AAF Training Command.” African American Army Air Force group at Tuskegee Army Air Field, Alabama](/articles/000/images/service-pnp-cph-3c30000-3c38000-3c38600-3c38636v.jpg?maxwidth=1300&maxheight=1300&autorotate=false)

![“She's a swell plane - give us more! MORE PRODUCTION [Riggs]” “She's a swell plane - give us more! MORE PRODUCTION [Riggs]”](/articles/000/images/208-aop-113-112-2013-001_a.jpg?maxwidth=1300&maxheight=1300&autorotate=false)