Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Lucy Stone .

Previous: Learning from Lucy Stone

Article

Lucy Stone is perhaps best known for her talents as a public speaker. Her speech at the 1852 Syracuse convention is credited as the final push that motivated Susan B. Anthony to join the women’s rights movement. Stone discovered her gift for public speaking while at Oberlin College. After graduation, she became a lecturer for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Both Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell were involved in the abolitionist movement. Anti-suffragists often criticized Stone because she chose not to take Blackwell’s last name, which they claimed undermined a husband’s traditional role as head of the family. Conversely, Stone argued, “A wife should no more take her husband’s name than he should take hers. My name is my identity and must not be lost.”

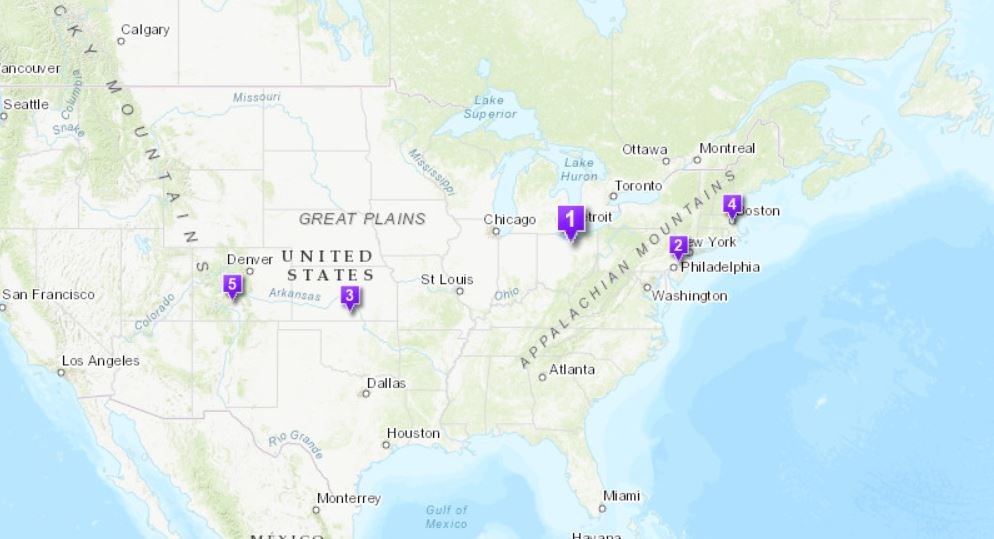

Stone was also the driving force behind several women’s suffrage organizations and events. In 1850, she organized the first national woman’s rights convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. During the late 1860s, Stone helped to establish the New Jersey and New England suffrage organizations. She also cofounded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in November 1869. This group promoted women’s suffrage on a state-by-state basis. Unlike the National Woman Suffrage Association, AWSA supported the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted Black men the right to vote. The two groups merged in 1890. After Stone’s death in 1893, her daughter Alice Stone Blackwell continued to fight for women’s suffrage.

When Stone graduated from Ohio's Oberlin College in 1847, she became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn her bachelor’s degree. Oberlin was the first college in the US to grant bachelor's degrees to women and the first to admit African American students. As a student, Stone founded America’s first debating society for college women. The unauthorized group initially met secretly in the woods and posted lookouts. To pay for her tuition, Stone taught in Oberlin's Preparatory Department. She discovered that women student teachers were paid half of what men received for the same job. Outraged, Stone threatened to strike and petitioned the Faculty Board. After several weeks, the Board raised women’s pay to the same rate as men.

Oberlin College was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014-08-30_10_39_31_View_of_the_New_Jersey_State_House_in_Trenton,_New_Jersey_from_the_north.JPG

After Stone and Blackwell moved to East Orange, New Jersey, she refused to pay taxes on their home. In December 1857, she argued that, like the US Founders, she would not pay taxes without political representation. To make up the tax revenue, the local authorities auctioned off some of Stone's furniture. In 1867, Stone brought women's suffrage before the state legislature. On March 6, she delivered the speech "Woman Suffrage in New Jersey" at the State House. The next year, she and her sister-in-law, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, petitioned the legislature about women’s suffrage and property rights.

The New Jersey State House is a contributing property in the State House Historic District. The district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Constitution_Hall-Topeka,_429_S._Kansas_Avenue,_Topeka,_KS.jpg)

Constitution Hall in Topeka served as Kansas’s first state capitol from 1864 to 1869. In this role, the building contributed to the women’s suffrage movement and the Impartial Suffrage campaign. The term “Impartial Suffrage” referred to a referendum, where people would directly vote on removing the word “men” from the state constitution. If successful, the measure would grant the right to vote to both African Americans and women. Kansas was the first state to hold a referendum on women’s suffrage. In 1867, Stone and Blackwell launched a lecture tour to promote Impartial Suffrage. The measure did not pass but inspired other western states to hold their own suffrage referendums.

Constitution Hall was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2008. It is part of the Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and a partner site of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program.

As the site of many Revolutionary-era planning meetings, the history of Faneuil Hall in Boston is steeped in the fight for equal rights. In 1873, Stone organized a women’s suffrage meeting for the New England Woman's Tea Party at Faneuil Hall. The meeting commemorated the centennial of the Boston Tea Party, which protested British taxation of the American colonies without their consent. Like the Revolutionaries, Stone argued that women should not be required to pay taxes without representation. Her argument drew a direct connection between the fight for women’s suffrage and the legacy of the country’s Founders.

Faneuil Hall was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. Faneuil Hall also sits within Boston National Historical Park and is a Boston African American National Historic Site.

Colorado became a state in August 1876. A women’s suffrage referendum soon followed in October 1877. During the month leading up to the vote, Stone, Blackwell, and Anthony visited many towns throughout the state in support. Many local newspapers expressed their distaste for the suffrage movement and Stone herself. Others described the excitement of the crowds that gathered to hear her speak. The Colorado Mountaineer reported that “[the Saguache] court house was overcrowded in the rush for seats. Lucy appears to be ubiquitous.” Saguache County’s first courthouse was located in an adobe building. This structure also served as a school and later a residence for jailers who worked at the county jail next door. Despite Stone’s efforts, women could not vote in Colorado until another referendum passed in 1893.

The Saguache School and Jail Buildings were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.

Colorado Mountaineer. “We learn from the Sagauche [sic] Chronicle that Lucy Stone Blackwell and husband recently addressed…” September 19, 1877. Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection.

Freedom’s Frontier. “Constitution Hall in Topeka.” Places to See. Accessed August 12, 2020.

Kansas Historical Society. “Women’s Suffrage.” Kansapedia. Last modified July 2017. Accessed August 12, 2020.

Karnauskas, Leslie. “The Road to the Vote.” History Colorado. Published November 7, 2019. Accessed August 12, 2020.

Kohlhofer, Merrill. “New England Woman's Tea Party.” Boston National Historical Park. Accessed August 12, 2020.

McMillen, Sally Gregory. Lucy Stone: An Unapologetic Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Lucy Stone .

Previous: Learning from Lucy Stone

Last updated: February 20, 2025