Last updated: August 24, 2022

Article

Places of Latino LGBTQ Gathering Spaces

Juana Alicia, Edythe Boone, Miranda Bergman, Susan Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton and Irene Perez, © 1994, 2000, 2010. All rights reserved. Mural images courtesy of the artists.

Gathering places such as parks, people’s living rooms, and city streets are foundational to identities and communities. In these spaces, LGBTQ Latinos formed groups, found refuge, resisted oppression, and created a deeper sense of what it means to be Latino and LGBTQ.

In spite of erasure and exclusion, the LGBTQ and Latino communities have preserved the symbolic and tangible remains of LGBTQ and Latino history. Even when historic places are no longer standing, art can document these stories and make the layers of history visible.

Explore the role of 6 historic places in celebrating Latino LGBTQ visibility and community in the US.

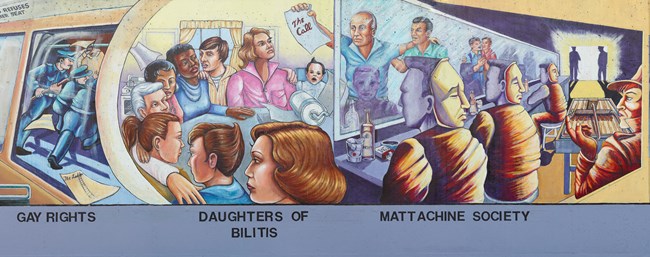

Judith F. Baca©1983. “Gay Rights,” detail from the 1950’s section of the Great Wall of Los Angeles. Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives SPARCinLA.org.

1. Great Wall of Los Angeles (Mural)

Latinos played a pivotal role in early LGBTQ activism, including two pioneering gay rights organizations.

Mattachine Society

Cuban immigrant and organizer Gonzalo “Tony” Segura, Jr. helped grow the LA-based Mattachine Society into a national organization.

Judith F. Baca©1983. Detail, longshot perspective of the 1940's section of the Great Wall of Los Angeles mural. Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives SPARCinLA.org.

Daughters of Bilitis

In 1955, Chicana activist Mary (last name unknown) cofounded the Daughters of Bilitis to create safe spaces for lesbians to socialize.

The Great Wall of Los Angeles mural depicts these events and other significant parts of LA’s history and culture. Between 1978 and 1984, Chicana muralist Judith F. Baca worked with a team of artists to create the 2,754-foot mural.

The Great Wall of Los Angeles mural was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2017.

Photo by Travis Mark. Courtesy of The LGBT Community Center. All Rights Reserved.

2. The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Community Center

Since its founding in 1983, the LGBT Community Center in New York City has served as a gathering space for several LGBTQ groups, including the Lesbian Avengers.

Cofounded by Cuban activist and playwright Ana Maria Simo in 1992, the Lesbian Avengers used direct-action tactics (nonviolent demonstrations such as marches and kiss-ins) to increase lesbian visibility.

Courtesy of The Lesbian Avengers. Photo by Morgan Gwenwald. All Rights Reserved.

The LGBT Center was designated a New York City Landmark in 2019. New York City is a Certified Local Government.

Juana Alicia, Edythe Boone, Miranda Bergman, Susan Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton and Irene Perez, © 1994, 2000, 2010. All rights reserved. Mural images courtesy of the artists.

3. The Women's Building

The San Francisco Women's Center (SFWC) emerged from radical and lesbian feminist movements in the 1970s. The SFWC purchased Mission Turn Hall in 1979 and renamed it The Women’s Building (TWB), a community landmark.

Many of the founding directors were women from various social and ethnic groups, including the late lesbian Puerto Rican activist Carmen Vazquez.

Juana Alicia, Edythe Boone, Miranda Bergman, Susan Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton and Irene Perez, © 1994, 2000, 2010. All rights reserved. Mural images courtesy of the artists.

In 1994, the building’s façade transformed. A group of 7 women muralists painted the Maestrapeace Mural on the building — weaving together art, history, fiction, gender, race, class, and sexuality.

Since 1979, TWB has stood as a gathering hub for groups, such as Somos Hermanas, Ellas en Acción, and Gay Latino Alliance, who achieved and continue to achieve social and gender equality for the community.

The Women's Building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.

Photo by Ian Poellet. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

4. Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico

The Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico in San Juan was the home of Puerto Rico’s first gay liberation organization between 1975 and 1976. It paved the way for LGBTQ visibility on an island with deep colonial ties to machismo and anti-homosexuality.

The organization provided educational and community services and published the magazine Pa'fuera! out of Casa Orgullo’s second floor. The magazine was distributed in gay libraries like Oscar Wilde Library in Greenwich Village and Lambda Rising in Washington DC.

Photo by Jerjes Medina Albino. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

Casa Orgullo’s backyard extended into the city streets by hosting public events and social celebrations. These parades, pageants, and protests were key to establishing a larger community and launching the gay liberation movement in Puerto Rico.

Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Image courtesy of Florida Keys Public Library. Photo by Raymond L. Blazevic. Creative Commons — Attribution 2.0 Generic — CC BY 2.0.

5. South River Drive Historic District

The Mariel Boatlift contributed to monumental change in US immigration reform and Miami's LGBTQ history. From the early 1900s, the US denied entry to LGBTQ immigrants, but the US also opened its doors to anyone fleeing communism, including LGBTQ Marielitos who were deemed “unrevolutionary” and exiled by the Castro regime. With the Immigration Act of 1990, the US amended its immigration policy to accept LGBTQ immigrants and remove homosexuality as grounds for denying entry to the US.

Photo by B137. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Marielitos established themselves within neighborhoods like Little Havana, working in department stores and hanging out in public spaces. The visibility of the trans and gay community became more prominent as Marielitos and LGBTQ immigrants from across Latin American and the Caribbean continued to make Miami home.

South River Drive Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

Image by Joseph A. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

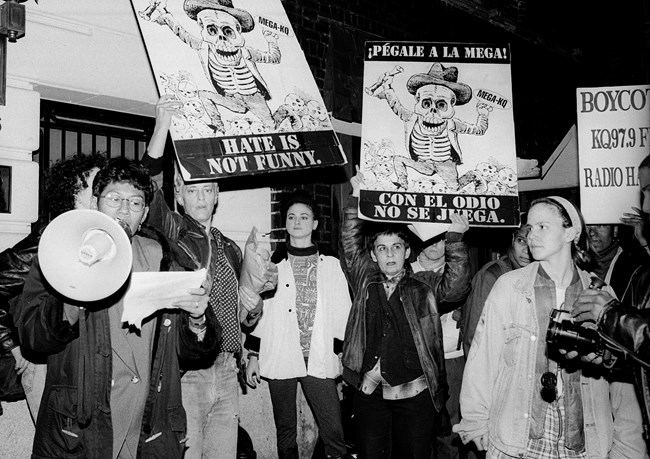

6. Chicago City Hall-Cook County Building

After being diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, Puerto Rican and Mexican political cartoonist Daniel “Danny” Sotomayor combined art with activism. He published over 200 cartoons criticizing government officials’ refusal to acknowledge AIDS and barriers to research funding, drug trials, and treatment.

Sotomayor also took to the streets as a cofounder of ACT UP Chicago. On April 24, 1990, over 5,000 demonstrators gathered to protest the American Medical Association and insurance industry’s response to AIDS. Sotomayor and other ACT UP Chicago leaders entered the Cook County Building. They hung a banner over the entrance to demand equal healthcare access for AIDS patients.

Chicago City Hall-Cook County Building was designated a Chicago Landmark in 1982. Chicago is a Certified Local Government.

The content for this article was researched and written by Melissa Hurtado, Heritage Education Fellow, and Jade Ryerson, Resource Assistant (Intern), with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Bibliography

Baldwin, Jessica C. “The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center Designation Report.” (Designation List 513 LP-2634). NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. Edited by Katie Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman. June 18, 2019. http://www.nyclgbtsites.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/LGBT-Community-Center.pdf.

Dowell, Chelsea. “Ana Maria Simo – Lesbian Avenger in the East Village.” Off the Grid (blog). Village Preservation. March 7, 2017. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2017/03/07/ana-maria-simo-lesbian-avenger-in-the-east-village/.

Gala, Santiago and Juan Llanes Santos. "Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico." National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Puerto Rico State Historic Preservation Office, San Juan, May 2, 2016. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail?assetID=e9873242-1a04-495f-98ac-b42b47e67aab.

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. "Guide to the San Francisco Women's Building/Women's Centers Records, 1966, 1972-2001." Online Archive of California. Published 2002. http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt696nb1jq/entire_text/.

Julio Capó, Jr. “Queering Mariel: Mediating Cold War Foreign Policy and U.S. Citizenship among Cuba’s Homosexual Exile Community, 1978–1994.” Journal of American Ethnic History 29, no. 4 (2010): 78-106. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerethnhist.29.4.0078.

Keehnen, Owen. “One Person Can Change the World: Sotomayor.” In Out and Proud in Chicago: An Overview of the City’s Gay Community. Edited by Tracy Baim with contributions by John D’Emilio, Jonathan Ned Katz, and Jorjet Harper. Chicago: Surrey Books, 2008.

The Lesbian Avengers. “An Incomplete History.” About. Accessed May 24, 2022. http://www.lesbianavengers.com/about/history.html.

Library of Congress. “The Daughters of Bilitis.” LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/before-stonewall/daughters-of-bilitis.

Library of Congress. “The Mattachine Society.” LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resources Guide. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/before-stonewall/mattachine.

Lo, Malinda. “The Women of Color Behind the Daughters of Bilitis.” Malinda Lo (blog). June 15, 2021. https://www.malindalo.com/blog/2021/6/15/daughters-of-bilitis.

Makkai, Rebecca. “They Were Warriors.” Chicago Magazine. April 7, 2020. https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/may-2020/oral-history-act-up-chicago-aids/.

National Park Service. “Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico.” Places. Last updated June 9, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/places/edificio-comunidad-de-orgullo-gay-de-puerto-rico.htm.

Springate, Megan E., ed. LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History. Washington, DC: National Park Service and National Park Foundation, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm.

National Park Service. “Women's Building, San Francisco, CA”. Places. Last updated March 19, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/places/womens-building-san-francisco.htm.

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. “Tony Segura Residence.” Sites. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/tony-segura-residence/.

Temkin, Maria, Ivan Rodriguez, and Michael Zimny. "South River Drive Historic District." National Register of Historic Inventory-Nomination Form. Bureau of Historic Preservation, Tallahassee, August 10, 1987. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/77843163.

The Social and Public Art Resource Center in LA. “The Great Wall – History and Description.” Programs. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://sparcinla.org/the-great-wall-part-2/.

Tags

- lgbt

- lgbtq

- lgbtqia

- lgbtq place

- lgbt history

- lgbtq history

- latino history

- latino heritage

- latino american history

- american latino heritage

- latino american heritage

- women's history

- women and the arts

- places of article

- places of...

- los angeles

- san francisco

- california

- new york city

- new york

- chicago

- illinois

- san juan

- puerto rico

- miami

- florida

- art

- arts and culture

- arts culture and education

- artist

- political history