Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Black Cowpokes in the American West .

Previous: Black Cowpokes of the Wild West

Article

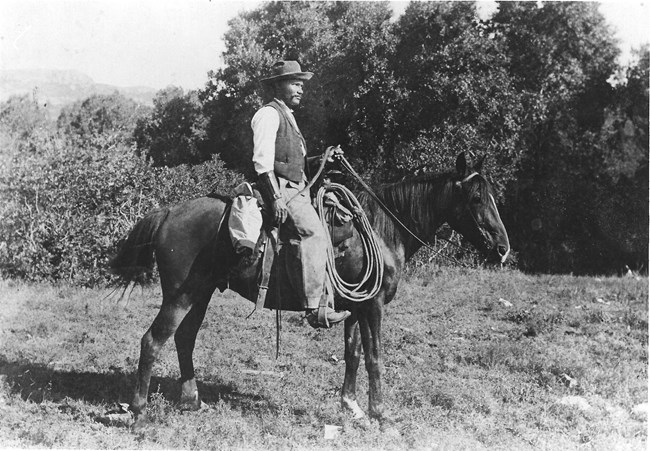

Cowboying is a profession that developed over the course of several centuries, from the 1500s through the present. The tradition of herding cows on horseback was brought to what is now North American by Spanish colonizers. These cattle herders were originally called “vaqueros.”

Cowboying was informally practiced in areas of what is now the southwestern US in the 18th and 19th centuries. Ranch owners living on the frontier needed skills in horseback riding and cattle herding to look after their livestock. By the late 1860s, the demand for beef had skyrocketed, and ranchers sought to sell their cattle on the national market. They hired cowpokes (another word for a cowboy or cowgirl) to herd steer (male cattle raised for beef) to train depots where the animals were then shipped across the country.

Cowboying was an appealing line of work for many African Americans seeking freedom from the racial discrimination prevalent in the South. It was a line of work that paid decent wages and white cowpoke were ususally firendly to their Black counterparts. By the late 1800s, one of every four cowpokes was Black. While the profession drew a number of African Americans in the aftermath of the Civil War (1861-1865), historical records indicate that people of African descent had owned cattle ranches and herded cattle in North America since the early 1700s. The story of the Black cowpoke is an important part of the history of the American southwest. Discover some of the places associated with Black cowboys and cowgirls.

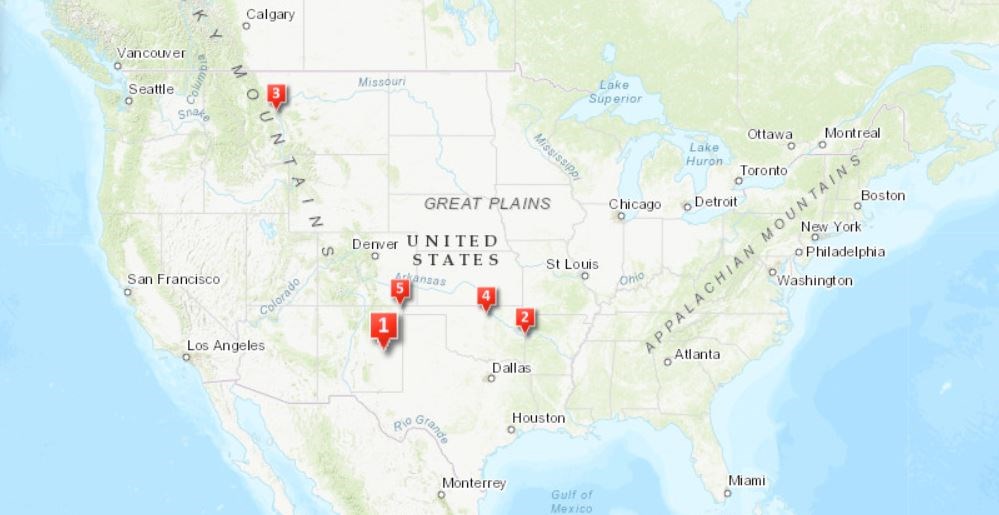

In 1866, Texas cowboys Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving saw a lucrative opportunity to make money selling cattle to Fort Sumner, located over the border in New Mexico. Now a National Register listing, Fort Sumner was built by the federal government in 1862. The fort and the neighboring reservation, Bosque Redondo, were originally established to forcibly detain thousands of Navajo and Mescalero Apache men, women, and children. After several years living on the reservation, people at Fort Sumner were starving. Hoping to make a profit selling beef to the hungry Navajo and Apache, Goodnight and Loving hired a group of cowboys to herd cattle from Texas to New Mexico. Black cowpoke Bose Ikard was one of the men paid to forge the trail, which became known as the Goodnight-Loving Trail. Ikard continued to work with Goodnight over the next several years, tracking and wrangling cattle across the several hundred mile trail. Ikard also protected Goodnight's valuables, and he often carried thousands of dollars in cash that he kept safe from bandits and raiding parties.

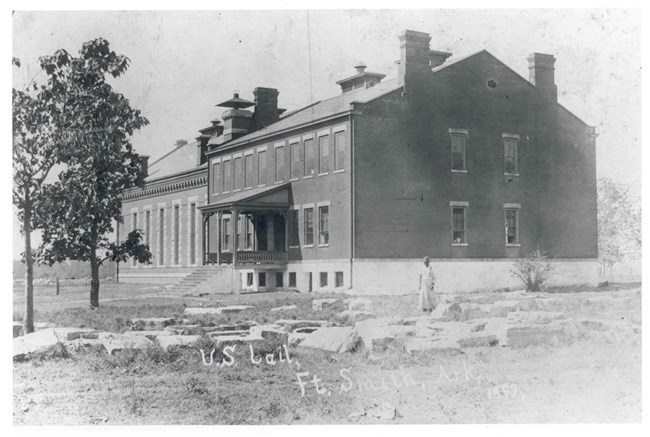

Frontier town Fort Smith was established in 1817 on the border between Arkansas and Oklahoma. The town, now a National Historic Site, was located just outside of Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) and was a stop on the Trail of Tears. The Indian Territory was governed by five tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole) that had their own governments, courts, and police. As the tribes were not allowed to arrest white or Black men who were not citizens of the tribes, this task fell to the deputy U.S. marshals who worked out of Fort Smith, including Bass Reeves. Born enslaved in Arkansas in 1838, Reeves eventually gained his freedom and found employment as a U.S. marshal. He was able to speak several Native languages, and was highly respected in his profession. Reeves worked as a marshal for 32 years, from 1875 to1907.

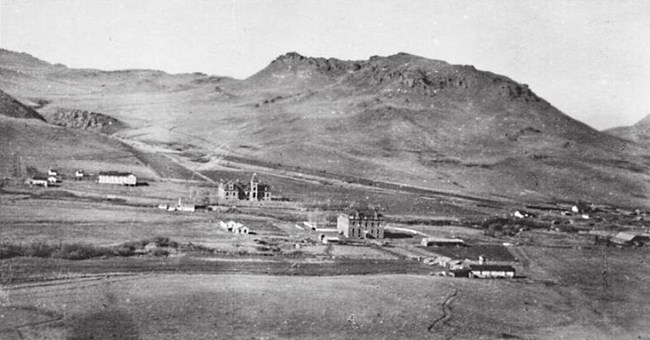

St. Peter’s Mission in Montana is a historic site listed on the National Register of Historic Places. While the mission was abandoned in the 1930s, it was once home to famous Black pioneer Mary Fields. She originally worked at a convent (a Catholic religious institution for women) in Toledo, Ohio until 1885 when she made the journey to Montana. A number of the Toledo nuns had moved to St. Peter’s to establish a school for American Indian girls, and Fields traveled over 1600 miles to help manage daily operations at the mission.

When Fields arrived in Montana in 1885, there were about 150 people living at the mission, including American Indian and white students as well as the staff.2 By cultivating a large garden and hunting game, Fields ensured that all the staff and students were fed. She also coordinated the delivery of supplies to the isolated mission. She lived on the property but refused to be paid for her work. When rumors spread that Fields was involved in a dual, she was banned from the mission by the bishop. But she took a job as a Star Route Carrier for the U.S. Post Office and delivered mail to St. Peter’s from 1895 to 1903.

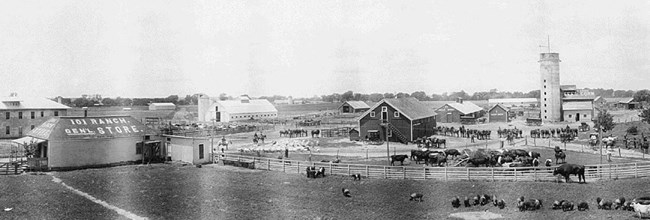

In 1903, Joseph, George, and Zack Miller inherited their father's extensive farm and cattle ranch in Oklahoma, now a National Historic Landmark. While the ranch was known for its crops, oil wells, and livestock, it was most famous for its wild west shows. One of the show’s biggest stars was African American cowpoke Bill Pickett. Born in Texas around 1870, Pickett learned the importance of being a skilled cattle wrangler from a young age. He developed his own tricks, including the “bulldogging” technique, which entailed wrestling the steer to the ground. In 1907, the Miller brothers took their show on the road. Bill Pickett and his fellow cowboys and cowgirls performed across the country, including at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

One of the most important archeological sites in the United States, Folsom Site, New Mexico, was discovered by cowboy George McJunkin. Born enslaved in Texas in 1851, McJunkin gained his freedom and learned the skills of cowboying from a Mexican vaquero. After herding cattle along the Santa Fe Trail for several years, McJunkin eventually took as job as a foreman on a cattle ranch near Folsom, New Mexico. In 1908, after a strong storm flooded the town, McJunkin rode through a nearby field where he found a very large animal bone. The bone was much bigger than that of a modern cow or horse, and McJunkin attempted to contact archeologists about his discovery. In 1926, four years after McJunkin's death, archeologists finally excavated the site. They determined that the area was once a marshland where humans had hunted and killed over 20 bison using hand-made tools. The most shocking discovery was that the tools dated to around 9000BCE! Archeologists originally thought that humans had only lived in North America for 2000 years. McJunkins's discovery helped archeologists prove that humans had been in North America much longer than previously thought. Folsom Site is now a National Historic Landmark.

Bibliography:

Durham, Philip and Everett L. Jones. The Negro Cowboys. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

Garceau-Hagen, Dee. Portraits of Women in the American West. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Hagan, William T. Charles Goodnight: Father of the Texas Panhandle. University of Oklahoma Press: 2012.

Hanes, Billy C. Bill Pickett, Bull-Dogger: The Biography of a Black Cowboy. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1989.

Hardaway, Roger D. “African American Cowboys on the Western Frontier.” Negro History Bulletin 64, no.1 (January-December 2001): pp.27-32.

Liles, Deborah M. and Cecilia Gutierrez Venable, eds. Texas Women and Ranching: On the Range, at the Rodeo, and in their Communities. College Station: Texas A&M, 2019.

McConnell, Miantae Metcalf. “Mary Fields’s Road to Freedom.” In Black Cowboys in the American West: On the Range, on the Stage, and Behind the Badge. Eds. Bruce A. Glasrud and Michael N. Searles. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma, 2016.

Nodjimbadem, Katie. “The Lesser-Known History of African American Cowboys.” Smithsonian Magazine, Feb 13, 2017.

Reindl, JC. “‘Stagecoach Mary’ Broke Barriers of Race and Gender.” The Blade. February 8, 2010, https://www.toledoblade.com/local/2010/02/08/Stagecoach-Mary-broke-barriers-of-race-gender.html.

Tennent, William L. John Jarvie of Brown’s Park. Cultural Resource Series No 7. Salt Lake City: Bureau of Land Management, 1982.

Wagner, Tricia Martineau. African American Women of the Old West. Guilford, CT: Twodot, 2007.

“Texans You Should Know: How a Black Cowboy’s Discovery Changed the Field of Archaeology.” Texas Monthly. Accessed 12.21.20. https://www.texasmonthly.com/the-culture/texans-you-should-know-how-a-black-cowboys-discovery-changed-the-field-of-archaeology/

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Black Cowpokes in the American West .

Previous: Black Cowpokes of the Wild West

Last updated: July 30, 2021