Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: African American Baseball .

Article

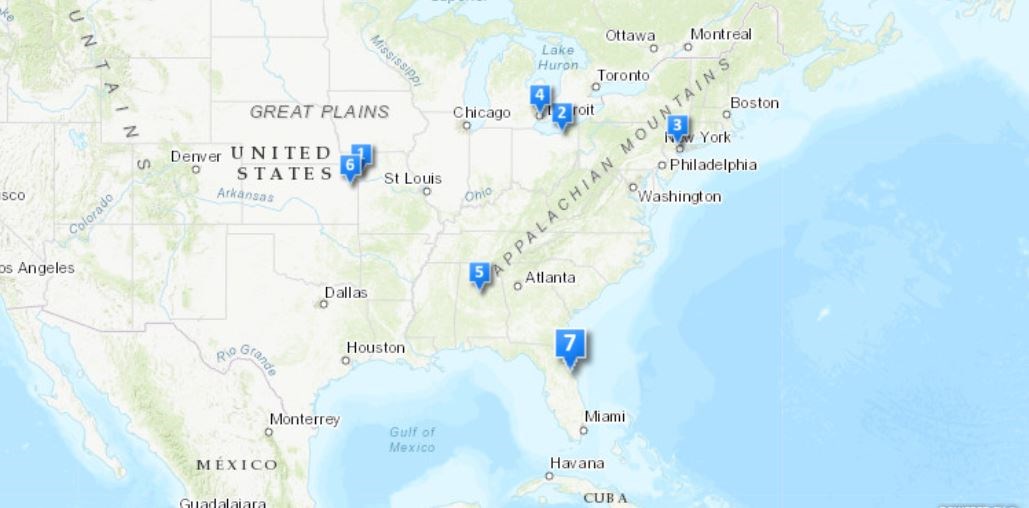

Places of Black Baseball

Photo by Mwkruse, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42299449

This article was reseached and written by Dr. Katherine Crawford-Lackey.

Baseball is an intrinsic part of American history and culture. The story of the sport’s evolution from informal game to professionalized sport is a mix of fact and myth. While baseball's origins are disputed, the first attempt to formally organize the sport in America occurred when sixteen clubs formed the National Association of Base Ball Payers (NABBP) in 1857. Up until this point, the style of the game varied by state and region. The Civil War (1861-1865) facilitated the spread of the sport and served to unify the rules as it was played in Union army camps.1

In 1869, the NABBP created a professional category for clubs that allowed team managers to pay their players if they wanted. The Cincinnati Red Stockings were the first to do so, making the team the first professional baseball team.2 More teams began to professionalize and broke away from the NABBP. These pro teams established the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NAPBBP) which operated from 1871 to 1875. The NAPBBP was replaced by the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, also known as the National League (NL), established in 1876. The American League was founded in 1901. In 1903, these two leagues partnered to create what is known today as Major League Baseball.

Racial segregation of baseball did not happen all at once. A number of teams had non-white players into the early 1900s. As team managers, reporters, and politicians began framing baseball as the “national sport” it reflected a white America, with white players. While there was not a formal policy on racial segregation, venues and team managers began discriminating against Black players and fans. The practice of denying Black teams from sporting events occurred as early as 1867. That October, the Pennsylvania State Convention of Baseball denied entrance to the Philadelphia Pythian Baseball Club, an African American team founded in 1865. A few months later, the National Association of Base Ball Payers implemented a color line, barring any team that had one or more African American players.3

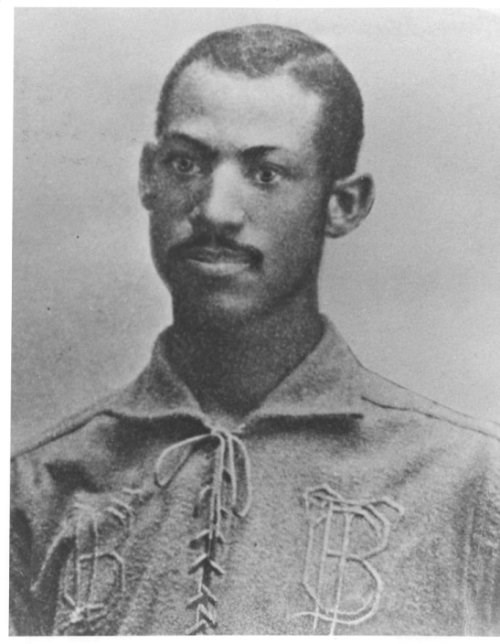

Once the sport professionalized, the Major Leagues, for the most part, adopted an all-white policy. There were rare exceptions, as in the case of Moses Fleetwood Walker, an African American ballplayer from Ohio. He was recruited by the Toledo Blue Stockings in the 1880s.4 But as Black players had few opportunities to join the Major Leagues, they formed their own teams. Some teams were composed of players of different ethnicities, including the Cuban Stars (a traveling team that played from 1907 to 1930) and the All Nations team. Playing from 1912 to 1925, the traveling All Nations team was composed of African Americans, American Indians, Native Hawaiians, Japanese Americans, and Hispanic Americans.5

Due to the leadership of Chicago American Giants owner Rube Foster, the heads of other Midwestern Black teams created the first Black league, the Negro National League (1920-1931). This league featured teams from Chicago, Cincinnati, Dayton, Detroit, Indianapolis, Kansas City and St. Louis. Black teams formed other leagues, including the Negro Southern League (on and off from 1920 -1951) and Eastern Colored League (1923-1928).6

The dynamics of segregated baseball had profound impacts on Black communities in America. All-Black teams became symbols of community pride. But when Black and white teams sometimes faced off, white players and fans harassed their Black counterparts. Some Negro League stadiums, such as Detroit’s Hamtramck Stadium, even had segregated seating. The baseball color line was an ever present reminder of white society's discriminatory practices.7

Brooklyn Dodger's general manager Branch Rickey had been looking to integrate Major League baseball. Robinson, who played for the Kansas City Monarchs, had always been dedicated to advancing African American civil rights. Rickey signed Robinson in August 1945 and sent him to play for the Montreal Royals, a Canadian team in the International League and the Class AAA team for the Dodgers. Robinson’s decision to join the Dodgers was not just about his career, it was also about challenging Jim Crow segregation laws and policies.

On March 17, 1946, African American Jackie Robinson played at City Island’s ballpark in Daytona Beach, Florida as a member of the Montreal Royals. When the Canadian team attempted to schedule training sessions at American ballparks, they were barred by stadium and team owners due to segregation policies in the US. City Island Ball Park was the first stadium to allow Robinson to play in the 1946 season. This was a first time that an African American could play in a professional base park since the late 1800s. To learn more about Robinson and this historic moment in American baseball, explore the Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan, “A Field of Dreams: The Jackie Robinson Ballpark.”

On April 15, 1947 Robinson debuted in the Major Leagues with the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, New York. After Robinson broke the color line, Black players were more inclined to sign with Major League teams, if given the opportunity. The Negro leagues began their decline and the official leagues were defunct by the end of the 1950s.8

There were many places associated with the history of Black baseball, including stadiums, fields, and athletic clubs. Unfortunately, a number of the original stadiums are no longer standing, including Municipal Stadium (Kansas City, MO), home of the Kanas City Monarchs and Griffith Stadium (Washington, D.C.), where the Homestead Grays once played. But some places did survive, and a few are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Below are some of the remaining buildings, ballparks, historic districts, and landscapes associated with Black baseball. Explore the history of Black baseball through place and feel inspired to do your own digging about the history of Black baseball in your community.

1. Paseo YMCA (Kansas City, MO)

Established in 1914, the Paseo YMCA was the birthplace of the Negro National League (NNL). When several African American baseball club owners met at the YMCA in 1920, they decided to create their own league. Rube Foster, a former baseball player and founder of the Chicago American Giants, led the effort to establish the NNL. Foster played for several teams throughout his career, including the Hot Springs Arlingtons (Arkansas), and the Chicago Union Giants. In 1902 he joined the Otsego Independents in Michigan, a white minor league team. Foster was their star pitcher for the season. A year later, he signed with the Cuban X-Giants and pitched this Negro League team to the 1903 Colored Championship title.

The NNL was significant because it was the first all-Black league to survive more than one season. It included franchises such as the Birmingham Black Barons, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Louisville White Sox, Memphis Red Sox, Milwaukee Bears, and Nashville Elite Giants. The NNL operated from 1920 to 1931 when it disbanded due to economic pressure caused by the Great Depression.9

The Paseo YMCA, now home to the Negro League Baseball Museum, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.

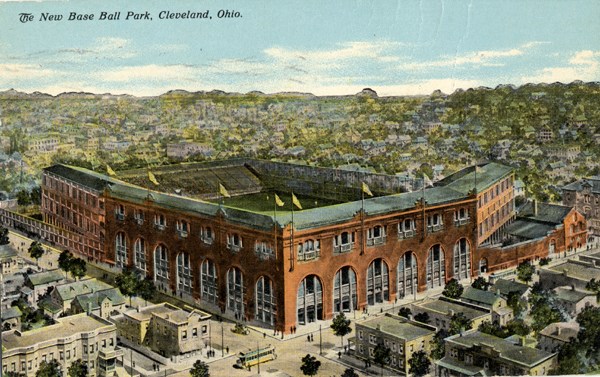

2. League Park (Cleveland, OH)

Originally constructed in 1891, Cleveland’s Historic League Park was rebuilt in 1910 and served as a multipurpose baseball and football field. The field was home to two teams in Major League Baseball, the Cleveland Spiders (National League) and the Cleveland Indians (American League). It was also home to the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League.

A number of Negro League teams played in the ballpark in the 1930s and 1940s before it became the official home of the Cleveland Buckeyes in 1942. One such game took place on a hot summer night in 1931, when the Homestead Grays (from Pennsylvanian) took on the House of David, a traveling Negro league team composed of players from Cuba. It was one of the only night games played at the stadium. Some of the most notable players of the time participated in the game, including Luis Tiant Sr., a legendary left-handing pitcher.

League Park was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

3. Hinchliffe Stadium (Paterson, NJ)

Hinchliffe Stadium, opened in 1933, stands as an important reminder of the many Negro leagues. This stadium is one of the only surviving Negro league home fields in the mid-Atlantic region. The New York Black Yankees regularly used the field from 1933-1937 and 1939-1945. The stadium hosted the 1933 Colored Championship of the Nation (the Negro leagues equivalent of the World Series). The home team, the New York Black Yankees, lost to the Philadelphia Stars.

From the mid-to-late 1900s, the stadium was used as a multipurpose field, hosting boxing matches, local football games, even concerts. A lack of funding has caused the structure to deteriorate in recent years. While there is renewed local interest in preserving the stadium, it is still in a state of disrepair (as of February 2021).10

Hinchliffe Stadium was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2013.

4. Hamtramck Stadium (Hamtramck, MI)

Mack Park, built in 1914, was funded by John Roesink, a local businessman. The park was the original home to the Detroit Stars, a Negro National League team. On July 7, 1929, the Detroit Starts were scheduled to play the Kansas City Monarchs in a doubleheader. Heavy rains soaked the field, postponing the games. Fearing a loss of profit, Roesink doused the base paths in gasoline to dry it out. (Setting the dirt on fire to dry up soggy ground was not unusual in baseball at the time.) But the fire raged out of control and destroyed the stadium.

To make up for the loss, Roesink built Hamtramck Stadium in 1930. The stadium is located in Hamtramck, a small city surrounded by Detroit. The stadium became the new home to the Detroit Stars and eventually the Detroit Wolves. The Detroit Stars were one of the original teams to join the Negro National League after it was founded by Rube Foster in 1920. The Detroit Stars signed legendary players such as Turkey Stearnes, who played at Hamtramck from 1923 to 1931. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000.11

Hamtramck was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2012.

5. Rickwood Field (Birmingham, AL)

Located in Birmingham, Alabama, Rickwood is the oldest professional baseball stadium in the US. It was funded by businessowner Rick Woodward and was built in 1910. The field was the home of the Birmingham Barons and the Birmingham Black Barons, a Negro League team that played from 1920 to 1960. A number of talented player joined the Birmingham Black Barons, including Satchel Paige. He played for the team from 1927 to 1930. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971.

The stadium was added to the National Register in 1993.12

6. 18th and Vine Historic District (Kansas City, MO)

A historically Black neighborhood in Kansas City, the 18th and Vine Historic District includes the Negro League Baseball Museum. The museum was founded in 1990 by a group of former baseball players.

The historic district is located 2 blocks north of where the Kansas City Monarchs once played. The Monarchs were a Negro League that played at Municipal Stadium (demolished in 1976) on 22nd Street in Kansas City. When the team was first founded in 1920, owner J.L. Wilson recruited players from the traveling All Nations team. In 1924, the Kansas City Monarchs defeated Hilldale in the Negro League World Series.

18th and Vine Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.

7. Jackie Robinson Ball Park (Daytona Beach, FL)

The City Island Ball Park was constructed in 1915. In 1946, Robinson played for the Montreal Royals, a Canadian team in the International League and the Class AAA team for the Brooklyn Dodgers. The team was made up of mostly white players, with the exception of Robinson. When the Montreal Royals attempted to schedule training sessions at American ballparks, they were barred by stadium and team owners due to segregation policies in the US. The City Island Ball Park was the first stadium to allow Robinson to play in the 1946 season. It was a symbolic moment that helped break down the baseball color line.

City Island Ball Park was renamed the Jackie Robinson Ball Park in 1990 in honor of Robinson’s debut on the field. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

In addition to the sources cited below, the National Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the Major League Baseball website provided information that informed this article.

Footnotes:

1 Debbie Schaefer-Jacobs, “Civil War Baseball,” (August 2, 2012), Smithsonian Institution, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2012/08/civil-war-baseball.html; William J. Ryczek, “Introduction,” in Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players, and Cities of the Northeast that Established the Game, eds. Peter Morris, William J. Ryczek, Jan Finkel, Leonars Levin and Richard Malatzky. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2013); David Block, Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2005).

2 Ryczek, Base Ball Founders.

3 “African-American players banned from professional white baseball,” Phillies.com, Major League Baseball website, https://www.mlb.com/phillies/community/educational-programs/uya-negro-league/african-american-players-banned; Robert W. Peterson, “Blacks in baseball.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/sports/baseball/Blacks-in-baseball.

4 John R. Hushman, “Moses Fleetwood Walker,” Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fleet-walker/

5 Stew Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History. (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006), 159; Timothy M. Gay, Satch, Dizzy &Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 25-26.

6 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951, (McFarland & Company, 2015); Robert W. Peterson, “Eastern Colored League,” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/sports/Negro-league#ref231893.

7 Alexis Morris, “The Ball Game is not over until the Last Man is Out: An Analysis of the African American Baseball Landscape in Detroit,” (Thesis, Syracuse University, 2016).

8 “Breaking the Color Line: 1940 to 1946,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/jackie-robinson-baseball/articles-and-essays/baseball-the-color-line-and-jackie-robinson/1940-to-1946/

9 Robert Charles Cottrell. The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant, (New York: New York University Press, 2001); Larry Lester, Rube Foster in Hist Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary. (McFarland & Company, 2012).

10 “Hinchliffe Stadium,” African American History Month, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/afam/2005/hinchliffe.htm.

11 Richard Bak. Turkey Stearnes and the Detroit Stars: Th Negro Leagues in Detroit, 1919-1933, (Detroit: Wayne State University, 1994), 184-186; “Historic Hamtramck is positioned for a Comeback!” Hamtramck Stadium website, http://www.hamtramckstadium.org; Greg Kowalski, Hamtramck, (Arcadia Publishing Inc., 2015), 78; Chris Epting, Roadside Baseball: The Locations of America’s Baseball Landmarks. (Solana Beach, CA: Santa Monica Press, 2019).

12 “History of Rickwood Field,” Rickwood Field website, https://rickwood.com/history-of-rickwood-field

Bibliography:

Augustyn, Adam. “Major League Baseball.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Major-League-Baseball

Bak, Richard. Turkey Stearnes and the Detroit Stars: The Negro Leagues in Detroit, 1919-1933. Detroit: Wayne State University, 1994.

Block, David. Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Cottrell, Robert Charles. The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant. New York: New York University Press, 2001.

Epting, Chris. Roadside Baseball: The Locations of America’s Baseball Landmarks. Solana Beach, CA: Santa Monica Press, 2019.

Gay, Timothy M. Satch, Dizzy &Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Harkness-Roberto, Michael and Leslie A. Heaphy. “The Monarchs: A Brief History of the Franchise,” in Satchel Paige and Company: Essays on the Kansas City Monarchs, Their Greatest Star and the Negro Leagues. McFarland Publishing, 2007.

Hushman, John R. “Moses Fleetwood Walker.” Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fleet-walker/

Kowalski, Greg. Hamtramck. Arcadia Publishing Inc., 2015.

Lester, Larry. Rube Foster in Hist Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary. McFarland & Company, 2012.

Morris, Alexis. “The Ball Game is not over until the Last Man is Out: An Analysis of the African American Baseball Landscape in Detroit.” Thesis, Syracuse University, 2016.

Muder, Charles. “Luis Tiant’s Brilliant Career Laded Him on Hall of Fame Ballot.” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame/golden-era/tiant-luis

Peterson, Robert W. “Blacks in baseball.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/sports/baseball/Blacks-in-baseball. “Eastern Colored League.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/sports/Negro-league#ref231893.

Plott, William J. The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951. McFarland & Company, 2015.

Ryczek, William J. “Introduction.” In Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players, and Cities of the Northeast that Established the Game. Eds.Peter Morris, William J. Ryczek, Jan Finkel, Leonars Levin and Richard Malatzky. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2013.

Schaefer-Jacobs, Debbie. “Civil War Baseball.” (August 2, 2012), Smithsonian Institution, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2012/08/civil-war-baseball.html

Swanson, Ryan A. When Baseball Went White: Reconstruction, Reconciliation, And Dreams of a National Pastime. University of Nebraska, 2014.

Thornley, Stew. Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006.

“African-American players banned from professional white baseball.” Phillies.com, Major League Baseball website, https://www.mlb.com/phillies/community/educational-programs/uya-negro-league/african-american-players-banned

“Breaking the Color Line: 1940 to 1946.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/jackie-robinson-baseball/articles-and-essays/baseball-the-color-line-and-jackie-robinson/1940-to-1946/

“Hinchliffe Stadium.” African American History Month, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/afam/2005/hinchliffe.htm.

“Historic Hamtramck is positioned for a Comeback!” Hamtramck Stadium website, http://www.hamtramckstadium.org

“History of Rickwood Field.” Rickwood Field website, https://rickwood.com/history-of-rickwood-field/

"How does baseball reflect the American Culture.” Washington State University, http://digitalexhibits.wsulibs.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/2016sphist417/sports/kui-hug

Tags

- african american

- african american history

- african american sites

- baseball

- sport

- sports history

- sports

- ohio

- ohio history

- new jersey

- new jersey history

- missouri

- missouri history

- florida

- florida history

- michigan

- michigan history

- detroit

- cleveland

- alabama

- alabama history

- birmingham

- national register of historic places

- jackie robinson

- nrhp listing

- national historic landmark

- curiosity kit

- places of article

- places of...

Last updated: July 30, 2021