Last updated: November 19, 2022

Article

Overcoming “Analysis Paralysis” through Better Climate Change Scenario Planning

A recently published paper shares best practices for using this valuable tool.

By Gregor W. Schuurman, Brian W. Miller, Amy J. Symstad, Amber N. Runyon, and Brecken C. Robb

Image credit: NPS

Rene Ohms is the former chief of resource management at Devils Tower National Monument. She is also a climate change scenario planning participant. Reflecting on the global threat of climate change and the challenges of responding to it, she recently observed, “Climate change isn't something that's going to happen 50 or 100 years from now; it's already here. And in most cases, we're way behind the eight ball in planning for it.” But it’s hard to plan for climate change. National Park Service resource managers don’t know exactly when those impacts will arrive or in what form. A single forecast is likely to be inaccurate, so it is risky to rely on any one prediction to make important decisions. At the same time, simply waiting for more or “better” information can encourage parks to continue using ineffective strategies. Scenario planning allows managers to work with uncertainty and prepare for a wide range of changes. It uses a small set of scenarios—descriptions of potential future conditions—to help them make robust decisions.

The major challenge in using scenario planning for adapting management to climate change is integrating complex, cutting-edge climate science with manager expertise. Our recent paper in the journal Conservation Science and Practice synthesizes current best practices for using climate change scenario planning. It describes a field-tested approach grounded in management priorities.

Image credit: NPS

Streamlining the Approach to Make It Easier

Participants in early National Park Service scenario planning often found the process long and laborious. In response, we have developed templates and “how-to” guides to help managers more easily identify sensitive resources, assess vulnerabilities, and choose climate-informed management strategies. Rather than performing each of these steps individually for each resource, our streamlined approach integrates them. Northern Great Plains Inventory and Monitoring Network Coordinator Kara Paintner-Green participated in early and more recent climate change scenario planning. She said that this updated approach “helps focus and prioritize” scenario planning so that “parks get the additional help” they need.

An Engaging Process Leads to Long-Term Change

Enthusiastic, committed participants develop useful scenarios. Climate change scientists and adaptation specialists who facilitate the scenario-planning process can engage them by translating science into products that are easy to understand. Some examples of these translations are in the National Park Service scenario planning showcase. This approach helps decision makers develop plausible scenarios that they then use to test and refine their management strategies. But this translation is a two-way process. Participants can use their expertise to identify climate sensitivities and adapt scientific information to their specific situation.

Image credit: NPS

"The scenario planning process definitely made me think long-term and change the way I do things instead of just fixing a problem like we always have."

Rich Lambert was Devils Tower National Monument’s chief of facility maintenance during the park’s recent scenario-planning process. He alerted us to the potential impacts of increasing humidity on historic wooden buildings built for a semi-arid climate. "When you combine higher temperatures with humidity, that’s when buildings stop working and pavements start heaving,” he said. “Once that ball is rolling, it’s not going to stop.” His remarks prompted us to calculate the potential future humidity for the scenarios he was working with. Lambert later admitted, “I used to be a climate skeptic, but all in all, the scenario planning process definitely made me think long-term and change the way I do things instead of just fixing a problem like we always have."

Image credit: NPS

Integrating with Park Plans for Greater Effect

To maximize the relevance and impact of climate change scenario planning, we collaborated with National Park Service planners to integrate climate change scenario planning with resource stewardship strategies. Resource stewardship strategies are park-specific plans that help managers achieve desired resource conditions. Ohms said that this kind of integration gave her park “a road map to follow.” It “identified several key steps we could take to start addressing present and future effects of climate change.” She added, “The park has begun implementing some of these, including hiring additional staff in the lengthening spring and fall seasons and re-evaluating plans to restore developed springs.”

Ohms said that this kind of integration gave her park "a road map to follow."

Practical Applications and Ongoing Evolution

The scenario planning process we describe in our paper transformed climate science and expert knowledge into management plans and on-the-ground actions for a diversity of resources at multiple parks. For example, it showed Wind Cave National Park that new approaches may be needed to maintain its forest-meadow balance under increasingly common fire-prone conditions. And it helped Badlands National Park identify the information it needs to better manage bison abundance to promote healthy prairie vegetation.

Image credit: NPS / Brian Kenner

The process continues to evolve. Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve did its scenario planning entirely remotely due to COVID-19. The park’s Research Stewardship and Science Lead Mark Miller said, “The virtual workshop format made it possible to accommodate simultaneous participation by subject matter experts located in Fort Collins, Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau, and elsewhere, in addition to park headquarters.” Scenario planning can help park managers avoid feeling paralyzed by the uncertainties of climate change. Tried and true practices for using this tool make it even more valuable.

About the authors

Gregor W. Schuurman is an ecologist with the National Park Service’s Climate Change Response Program. He works with parks and partners to understand and adapt to a wide range of climate change impacts. His work focuses on 1) incorporating climate science into management and planning, 2) producing and synthesizing management-relevant science, and 3) developing climate change adaption tools and concepts. Image courtesy of Gregor Schuurman.

Brian W. Miller is a U.S. Geological Survey research ecologist with the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center, one of nine regional centers in the U.S. He works with natural and cultural resource managers and local communities to help fish, wildlife, water, land, and people adapt to a changing climate. Brian uses scenario planning and ecological simulation modeling to help partners navigate climate change impacts and adaptation options. Image courtesy of Brian Miller.

Amy J. Symstad is a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Her research focuses on the plants of Northern Great Plains grasslands. She works with National Park Service and other land managers on issues ranging from invasive species and fire to climate change and drought. Image courtesy of Amy Symstad.

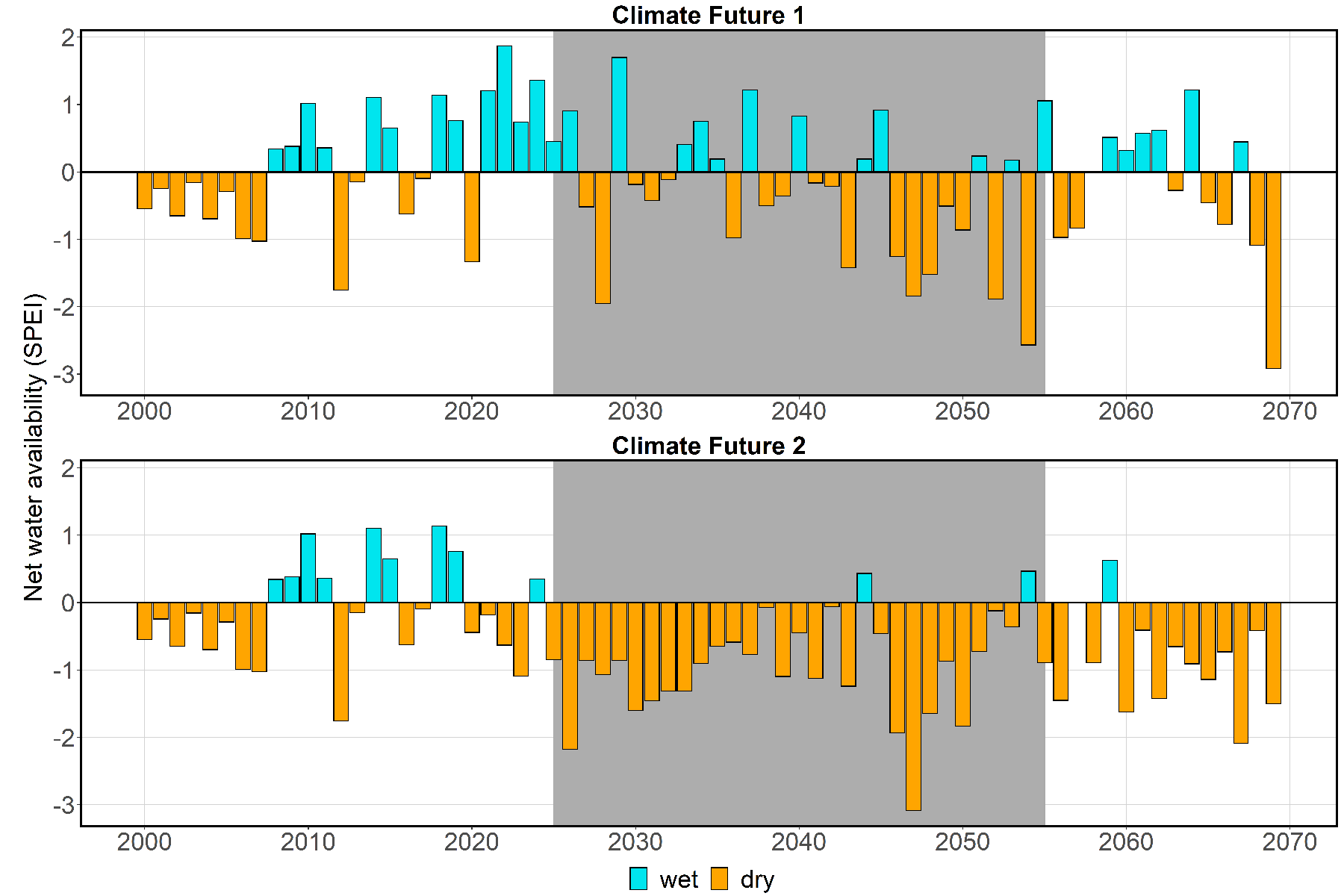

Amber N. Runyon is an ecologist with the National Park Service’s Climate Change Response Program. She collaborates with park managers to provide management-relevant projections of future climate that serve as the basis for climate-informed planning. Image courtesy of Amber Runyon.

Brecken C. Robb is a biologist with the Fish and Wildlife Service Science Applications Program. She supports wildlife conservation and restoration and climate change adaption by bringing together partners to develop shared values, tools, and scientific information. She recently worked with the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center and the NPS Climate Change Response Program on climate change scenario planning. She is drawing on that experience in her Fish and Wildlife Service work. Image courtesy of Brecken Robb.

Tags

- devils tower national monument

- wind cave national park

- wrangell - st elias national park & preserve

- scenario planning

- climate change

- gregor w. schuurman

- brian w. miller

- amy j. symstad

- amber n. runyon

- brecken c. robb

- in brief

- ps v36 n1

- park science magazine

- park science journal

- stories by women authors

- stories by women scientists