Part of a series of articles titled Whose Story is History? The Diverse History of Grand Canyon.

Article

Native Art and Activism of the Grand Canyon

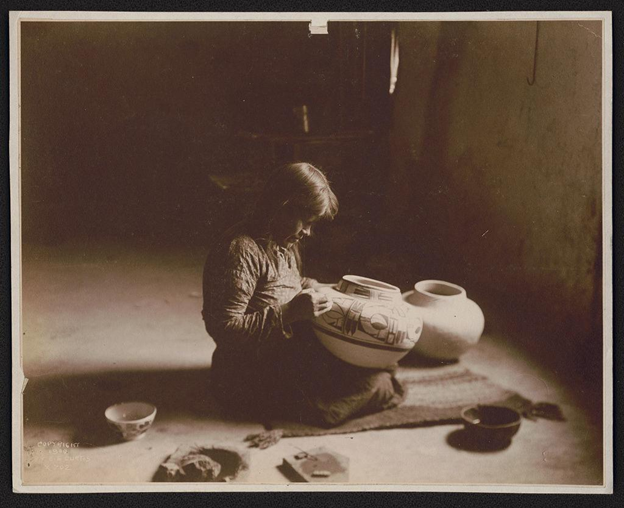

“When I first began to paint, I used to go to the ancient village and pick up pieces of pottery and copy the designs. That is how I learned to paint. But now, I just close my eyes and see designs and I paint them.” - Nampeyo 1

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Nampeyo was a Hopi woman born around 1860 at Hano, also known as Tewa Village, on First Mesa in Arizona. Her mother, White Corn, taught her how to make pots. At the age of 19, Nampeyo began studying pottery shards she found at archaeological sites to inspire her creations. Her artwork became so well known that her potter would have a sticker noting, "Made by Nampeyo," rather than the standard "Made in Hopi." In 1905, she moved into Hopi House at the Grand Canyon with her family for a three-month stay. Nampeyo returned home to First Mesa for the planting season, and upon her mother’s passing became the matriarch of the Corn Clan. While her tenure at Hopi House was brief, only returning once more for three months in 1907, Nampeyo created a lasting legacy. Her pottery continues to inspire artists and can be found in museums around the world to this day.

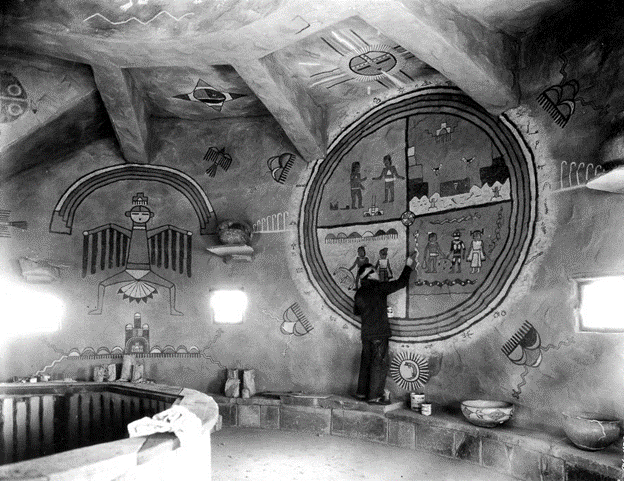

NPS

Fred Kabotie was another important artist in Grand Canyon history. Born in 1900 on the Hopi Reservation, he worked as in illustrator and gained great acclaim in the 1920s when his exhibit was showcased in New York City. In the 1930s, he worked as a tour guide and shop manager for Fred Harvey and was hired to paint murals in a traditional Hopi style on the walls of the new Desert View Watchtower, and he later served as the caretaker of the Watchtower. Kabotie's paintings, which can be seen on the second floor of the Watchtower, depict the first Indigenous man to travel down the Colorado River. His mural was a response to the popularly held belief that John Wesley Powell was the first person to navigate the Colorado River.

"I painted the Snake legend showing that the first man to float through the canyon was a Hopi -- hundreds of years before Major John Wesley Powell's historic Grand Canyon trip in 1869." Fred Kabotie2

Artists from the Grand Canyon’s affiliated tribal communities not only created influential works of art, but also long last impacts on their nations.

BANCROFT LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA / DANE COOLIDGE (BANC PIC 1905.17171:47)

Hastíín Tłʼa’s mother and sister taught Tłʼa weaving from a young age. It was Tłʼa’s uncle who shared the skills of traditional chanting and sandpainting, both important healing practices in the Navajo community. Learning these chants is an incredibly intricate skill and requires intense training. Tłʼa mastered many chants over the years and helped to immortalize these important traditions. Hastíín Tłʼa also preserved traditional weaving techniques despite religous persecution.

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION / JOHN K. HILLERS

Even We’wha’s advocacy could not stop the eventual pressure from the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs. Like many tribal communities across the country, the Zuni faced violence, forced assimilation, and loss of cultural tradition. This included pressure to no longer recognize lhamana individuals like We’wha, and to force Two-Spirit individuals to assimilate to western gender roles and presentation. This forced assimilation was felt by many Native communities across the country. Though Two-Spirit people have existed since time immemorial, Indigenous people coined the term "Two-Spirit" in 1990 during the Third Annual Inter-tribal Native American, First Nations, Gay and Lesbian American Conference. This was a means to rediscover and reclaim an important part of their cultural traditions and identities. It has since been embraced as the best way to articulate a tradition that has always existed in many Indigenous cultures. Two-Spirit individuals have been documented in at least 155 tribes, although it is important to note that Indigenous communities are not a monolith and so this term cannot always be used universally.

CLINE LIBRARY, NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIVERSITY (NAU.PH.95.48.1137)

Many Indigenous tribes continued to fight for their right to their homelands and the importance of preserving their cultures. Ethel Jack of the Havasupai Tribe was another artist who fulfilled the role of advocate and activist. Jack was born in Havasu Canyon in Supai in 1908. She was a talented basket weaver and sold some of her work to the Smithsonian. Before the Grand Canyon became a National Park, the Havasupai people spent the summers farming plateaus that are now within park boundaries. By the 1880s, White settlers began to encroach onto Havasupai land. In 1880 the Havasupai were forced onto a reservation, the size of which was dramatically decreased in 1882. The reservation contained only 518.6 acres. Ethel Jack’s grandfather, Billy Burro, continued to farm the lush plateau in what is known today as Havasupai Gardens. Ethel Jack had found memories of her grandfather’s laughter on the farm. Billy Burro was physically forced off this land in 1928 by two park rangers. In 1942, Ethel Jack’s husband, Clark Jack, was hired by the Park Service to maintain Bright Angel Trail. He also took tourists on mule trips through the land Jack’s grandfather had once been forcibly removed from. Ethel and Clark Jack lived on this land for a year as National Park Service employees, but generational memories and trauma remained.

Many Havasupai people lived in Supai Camp within the park, many employed by the National Park Service. In 1955, the National Park Service told any Havasupai individuals who were not employed by the NPS to leave Supai Camp, and then Grand Canyon National Park and concessioners began terminating the employment of many Havasupai tribal members. Park officials then demolished the remaining homes in Supai Camp. The Havasupai Tribal Council called upon Ethel Jack to advocate for their people. Jack traveled to Washington, DC to demand the return of their lands. She worked with governmental officials on bills, spoke to representatives, and waited long hours in government buildings for results. She said, “This isn't for me, it is for the younger members of the tribe.” In 1975, Ethel Jack and other tribal members succeeded in securing 185,000 acres for the Havasupai Tribe.

Ethel Jack said of sharing the news with young members of the tribe, “I’ll tell them that the land is our grandmother and our grandfather, for it feed us and provides for us. Then the land was taken from us, and we were alone for many years. But now we have our grandmother and grandfather back. I’m just so very happy.”3

Many inspiring Indigenous artists have influenced the park. They have shown how the Grand Canyon and tribal communities are intrinsically connected. This influence is not only seen at the Grand Canyon in Hopi House or at Desert View Watchtower. This impact can also be seen in beyond the walls or rim of the canyon, throughout Indigenous communities and the country at large.

1 Kramer, Barbara. Nampeyo and Her Pottery. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

2 Kabotie, Ed. "Native American Artist Fred Kabotie." Sharlot Hall Library & Archives, June 29, 2017. https://la.sharlothallmuseum.org/index.php/blog/cat/2017DP/post/native-american-artist-fred-kabotie/.

3 Leavengood, Betty. Grand Canyon Women: Lives Shaped by Landscape, 3rd ed. Grand Canyon, AZ: Grand Canyon Association, 2014, 195-196.

"Desert View Watchtower," American Southwest Virtual Muesum, https://swvirtualmuseum.nau.edu/wp/index.php/national-parks/grand-canyon-national-park/desert-view-watchtower/.

Brandman, Mariana. "We'wha," National Women's History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/wewha.

Crawford-Lackey, Katherine and Megan Springate. Identities and Place: Changing Labels and Intersectional Communities of LGBTQ and Two-Spirit People in the United States. Berghahn Books, 2019.

Hirst, Stephen. I Am the Grand Canyon: The Story of the Havasupai People. 3rd ed. Grand Canyon, AZ: Grand Canyon Association, 2006.

Leavengood, Betty. Grand Canyon Women: Lives Shaped by Landscape. 3rd ed. Grand Canyon, AZ: Grand Canyon Association, 2014.

Roscoe, Will. "Sexual and Gender Diversity in Native America and the Pacific Islands," in LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History, edited by Megan E. Springate. Washington, DC: National Park Foundation, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/lgbtqheritage/upload/lgbtqtheme-nativeamerica.pdf.

Last updated: October 11, 2024