Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.

Previous: The Places of Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Article

This Curiosity Kit Educational Resource was created by Katie McCarthy a NCPE intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was born in Guangzhou (Canton), China in 1896, and immigrated to New York City in 1905 to go to school. As a teenager and young adult, Lee participated in suffrage parades and wrote papers supporting the women’s suffrage movement. In 1917, the state of New York recognized the voting rights of women living within its borders. Three years later, the federal government signed the 19th amendment into law, nationally recognizing a woman’s right to vote. However, Lee was still not legally allowed to vote. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 denied Chinese immigrants, like Lee, the right to become citizens. Because citizenship is required to register to vote, the Act prohibited Chinese immigrants from voting. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, but we don’t know if Lee ever became a US citizen or if she ever voted. Lee did stay in New York City for the rest of her life, becoming the first Chinese woman to receive a PhD from Columbia University, acting as the director of the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City, and founding the Chinese Christian Center. You can find out more about Lee by visiting this article about her and by exploring the Places of Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.

Explore the life of Mabel Ping-Hua Lee by learning about the causes she participated in.

Identify ways in which people are excluded from participating in our democracy, for example through being unable to vote or unable to become a citizen.

Research ways in which people advocate for civil rights, both historically and in your community.

Combine visual information with other information in print and digital text.

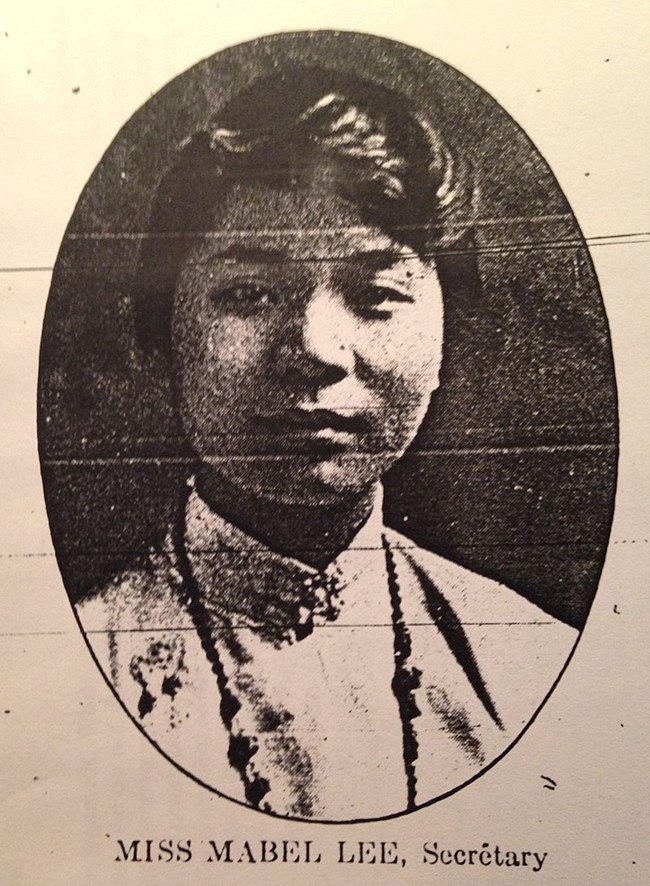

What does this image tell us about Mabel Ping-Hua Lee?

What do you think it implies about attitudes at the time about which people can participate in civics?

As a teenager and young adult, Mabel Ping-Hua Lee participated in the women’s suffrage movement, including marching in suffrage parades. During suffrage parades, Lee and others like her carried banners and wore pins sharing their message. You can learn about the symbols suffragists wore and used by reading this article, and by doing your own research online at sites like the Library of Congress, National Archives, or the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. After completing your research, it’s your turn to create a suffrage sign or banner! What symbols and colors will you use? If your creation has a slogan, what will it say? How big will your banner or sign be?

The campaign for women’s suffrage was one of many civil rights movements in the 20th century, and many people continue to work today for equality and equity. After completing your suffrage banner or sign, you may choose to create another for a contemporary cause you care about. How is this banner or sign different from the one you made for suffrage? Are there particular symbols or colors that have value to your cause? What kinds of slogans will you use? On what occasion would your banner or sign be displayed?

For much of her life, Lee’s ability to become an American citizen was constrained by the Chinese Exclusion Act. This Federal law was in place from 1882 to 1943. It prevented Chinese immigrants from becoming citizens. Since the mid-1800s, federal laws have determined who can immigrate to the United States. These laws include the Immigration Act of 1891, the Immigration Act of 1917, the Immigration Act of 1924, the McCarran-Walter Act (1952), the Immigration and Nationality Act (1965), and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) (2012). Other agreements or programs, like the Gentlemen’s Agreement with Japan or the Bracero Program with Mexico, although not laws, also helped to determine who could live and work legally in the Untied States.

After choosing one of the Acts, agreements, or programs in the list above, conduct research online or at a library to learn more. As you do, consider the following questions:

Who was affected by this law?

Who supported the law? What arguments did they make in favor of the law?

Who was against the law? Why did they think it should not be enacted?

What were the key steps that led to this law to be passed?

How did this law change immigration policy?

How long did this law last? What was it replaced by? Why was it replaced?

How did these laws affect people of your community or neighboring communities?

The Places of Mabel Ping-Hua Lee highlights the places where Lee lived, learned, worked, and protested. Today, our communities often have special places where people go to make their opinions known, like courthouses, civic buildings, or parks. Where might those places be in your community? If you don’t know, what resources can you use to find out? Once you have two or three places, it’s your turn to create your own “Places Of” article! As you do so, think about the following questions:

What is this place normally used for?

What does this place look like? Sound like? Smell like? Feel like?

What kinds of activities happen here? What do the people who raise their voices there care about?

Why do concerned people gather at this particular location? Why is it special?

How do people in your community feel about this place?

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.

Previous: The Places of Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Last updated: April 7, 2021