Part of a series of articles titled Whose Story is History? The Diverse History of Grand Canyon.

Article

Company 818 and Segregation in the Civilian Conservation Corps

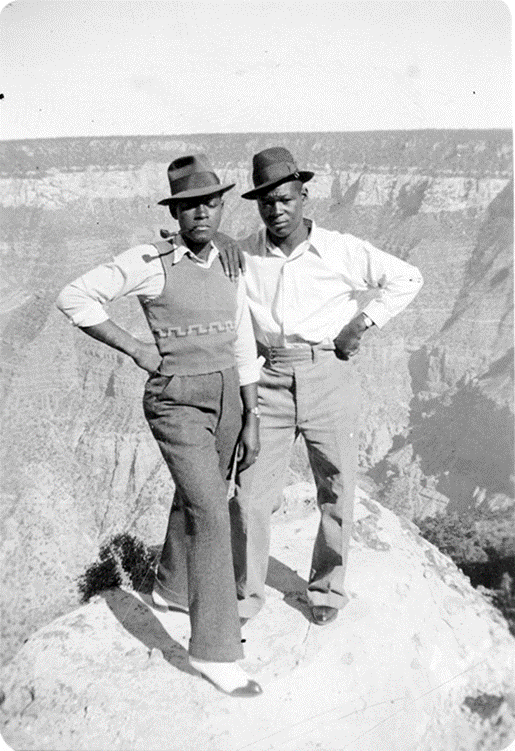

NPS Photo

"It [The CCC] was extremely well-conducted. It made, out of what could have been a dreadful flop and a dreadful hazard, a project that was intelligent, well-behaved, and therefore is well thought of in the community. We did it by getting the Army to run it, the Forest Service to direct its work. We kept them in order and the Forest Service selected good projects. Although it was an expensive form of relief, it accomplished a good deal and was invaluable in the training of young men." - Frances Perkins1

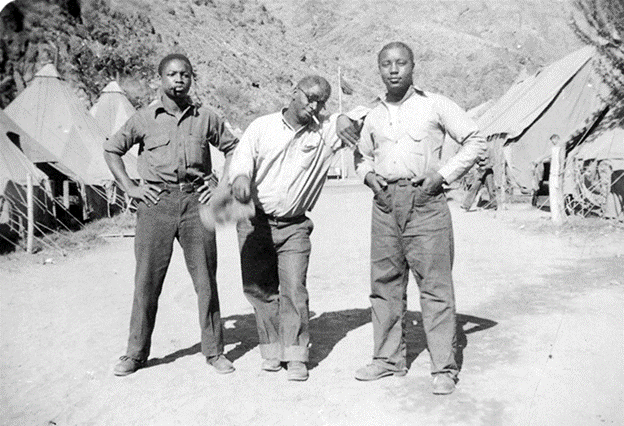

Grand Canyon NP Museum Collection

The first person enrolled in the CCC on April 1, 1933. The CCC set out to enroll a percentage of Black people that reflected the population of African Americans in the 1930 state census. This meant a cap at 10% of enrollment, but this did not account for the disproportionate impact that the depression had on communities of color. However, in some locations, it was a challenge to get any people of color enrolled. In many states with large Black American populations, no Black people had been selected to join the CCC.

Grand Canyon NP Museum Collection

Several companies were stationed at the Grand Canyon from 1933 to 1942. Company 819 worked on the South Rim of the canyon and on Bright Angel Trail. From 1933-1936 Company 818 worked on the North Rim during the Summer and the bottom of the canyon during the winter. This crew built the most difficult trail in the park, the Colorado River Trail.

Most Black CCC enrollees at the canyon were forced to be domestics and cooks and lived in segregated housing. John B. Scott was enrolled in company 818 at the Grand Canyon in June of 1935 when he was 19 years old. This crew seemed to be an exception and when working at Phantom Ranch, Black and White enrollees did the same trail work. Scott, a Black man, became a seasoned trail worker and trained and monitored new enrollees. Scott even stepped in and saved new enrollees lives by pulling them away from falling rocks. Scotts contributed and work as printing staff with the camp newspaper called ACE in the Hole and was the photographer of many treasured historical photographs.2 Company 818 not only made Black Americans feel comfortable but welcomed others from minority communities as well. Manuel Fraijo, a man of Hispanic heritage, enrolled in the CCC at Grand Canyon and chose to join company 818. He was originally in company 819, but as soon as he arrived at the canyon, Fraijo said that the “. . . sergeant proceeded to hassle us about our national heritage and tell us how lucky we were to be a part of his camp. . . I wanted very little to do with this sergeant.” 3

Grand Canyon NP Museum Collection

In 1935 Robert Fechner, the director of the CCC, was tired of receiving complaints regarding the program's integration. In 1935 he ordered, “complete segregation of colored and White enrollees.” Even though discrimination went against the law that created the CCC, Fechner asserted that “segregation is not discrimination.” By 1936 almost all Black Americans were placed into the segregated companies overseen by White officers. This policy ended up increasing the need for all Black companies, which increased the protests from White communities. This led Fechner to restrict the enrollment of Black Americans all together. It was not until 1941, one year before the CCC was dissolved, that African Americans were encouraged to enroll again.

Sources:

1 Dean Albertson interview of Frances Perkins. For the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University, 1951 and 1955.

2 Audretsch, Robert W. Shaping the Park and Saving the Boys: The Civilian Conservation Corps at Grand Canyon, 1933-1942. United States: Dog Ear Pub., 2011.

3Ibid

Margaret Hangan (2020) Finding African American History in the West, KIVA,

86:2, 149-155, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2020.1756096

Last updated: February 22, 2022