Part of a series of articles titled Whose Story is History? The Diverse History of Grand Canyon.

Article

“Little Mexico” and Creating Community

NPS

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / JACK DELANO

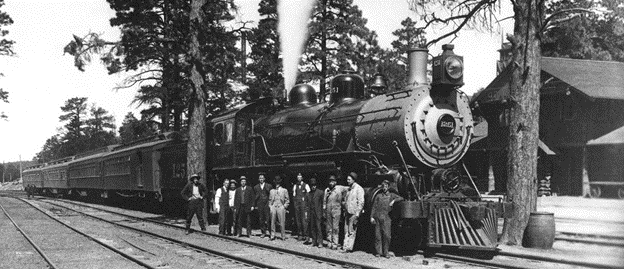

Between 1919 and 1929, AT&SF needed to build more infrastructure inside the park. This was a response to the increased number of tourists the trains were bringing to the canyon. The company contracted Robert E. McKee, General Contractor, Inc. to oversee the project. AT&SF and McKee relied on the labor of immigrants from Mexico, but they did not provide sufficient benefits for these individuals.

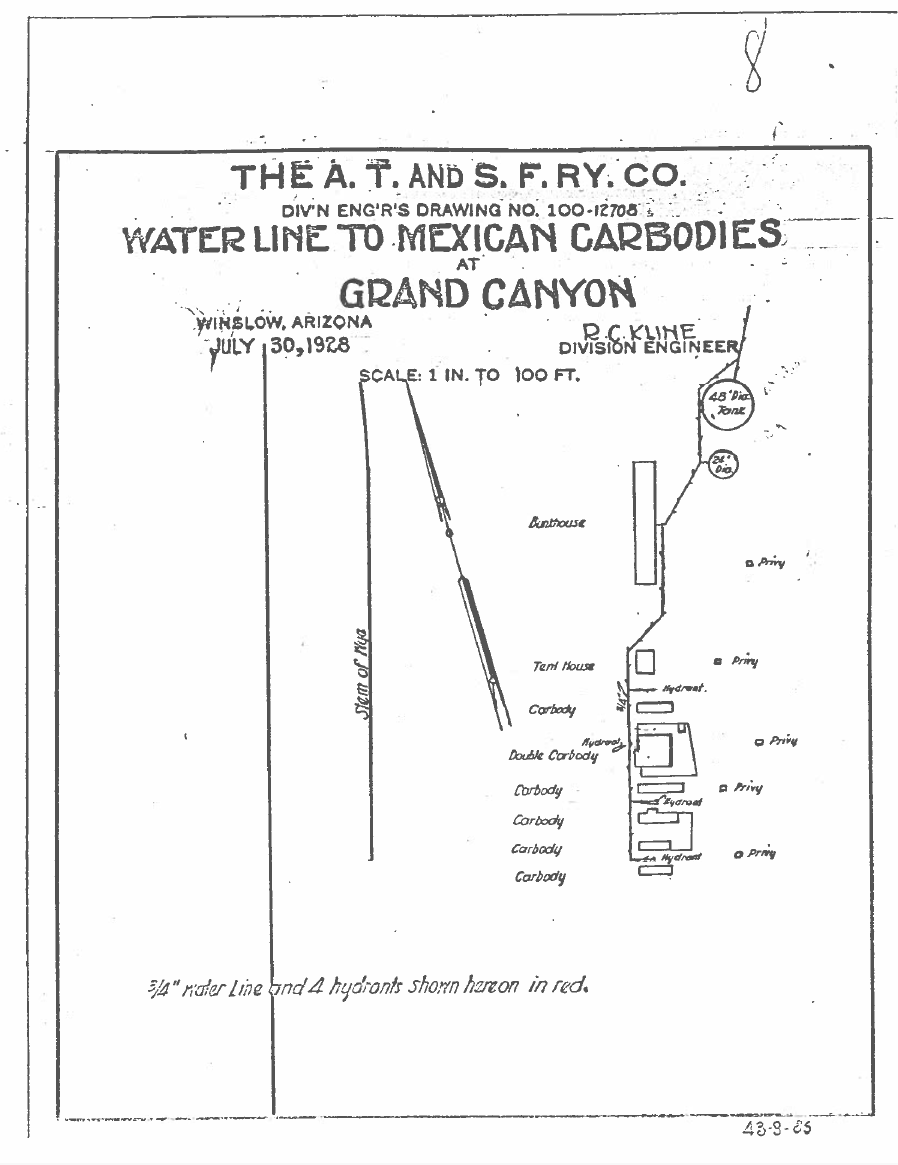

AT&SF and McKee provided no housing or food, which was normally customary for rural projects of this nature. Immigrant laborers who worked on the South Rim were on their own to create a sustainable life for themselves. The National Park Service provided temporary shelter permits. The community created their own basic shelters organized in camps. Abandoned boxcars and tents often housed many Mexican laborers and their families. This community formed just south of Grand Canyon Village and was dubbed by some as, “Little Mexico.”

NPS

AT&SF and McKee not only did not provide housing, but they also did not offer to feed their employees. Bright Angel Hotel had a lunch counter, but most Mexican laborers did not eat there. A park ranger at the time assumed that the “lower class laborers” felt it was “too expensive” or “felt out of place.” The superintendent at the time wrote, “Indeed, it would not be very pleasant for the tourists stopping at Bright Angel to go into the counter and be forced to ‘fall in’ with a lot of Mexican laborers just off the job.”1 This perspective on the social standing of Mexican immigrant laborers only exacerbated the inequality in access to housing and food.

Park staff noticed the poor treatment and living conditions of the community and tried to rectify the situation. In 1926 the park’s Acting Superintendent, George Bolton, wrote a letter to the AT&SF’s Chief Engineer W.K. Etter.

Bolton said, “It seems to me personally that a contractor when he is figuring on a job in an isolated place, should take into consideration the taking care of his labor gang. . . They should take care of or provide a place where everyone that works for them can be assured food or shelter.”2

NPS

Immigrants from Latin and South America continued to be forced into poor labor communities throughout the country. Many fought for labor rights throughout the early 1900s and even today. Hispanic Americans played an essential role in the labor movements in the following decades.

Despite the many challenges that Mexican laborers faced while living in Grand Canyon, many were able to form strong community bonds. The people of “Little Mexico” were able to physically create their own space at the canyon. Once they finished building infrastructure at the South Rim, it is likely that the Mexican American laborers dispersed and moved on to other employment opportunities. Mexican Americans at the Grand Canyon completed much of the infrastructure that we value today.

Citations and Sources:

1 Reid, Jack. Historically Under-Represented Persons or Groups in the Grand Canyon Region. Report of Findings and Research Design, 1-7.

2 Ibid.

3 Anderson, Michael F. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon, AZ: Grand Canyon Association, 2000, 94. https://npshistory.com/publications/grca/adhi.pdf.

Garcilazo, Jeffrey Marcos. Traqueros : Mexican railroad workers in the United States, 1870 to 1930. Denton, TX: UNT Press, 2012.

Vargas, Zaragosa. American Latino Theme Study: Labor. National Park Service, 2013. https://www.nps.gov/articles/latinothemelabor.htm

Last updated: October 11, 2024